This perplexing and twisting film from Gakuryu Ishii opens beneath a steel bridge in downtown Tokyo. In high contrast black and white, reminiscent of the street photography of Daiydo Moriyama, we’re dumped amidst broken furniture and an umbrella stand. People are living here at least semi-permanently. A large cardboard box suddenly rights itself, and we are presented dead-on with an infinitely dark rectangular hole, a 16:9 shaped peephole on the world.

From inside the box we are granted a hazy view of passing pedestrians, and a deep voice recounts the philosophy of the Box Man. This is no homeless person, discarded by society, but someone who has made a purposeful choice. The voice announces his superiority to the people he observes who are merely blinded by a fake reality, whereas he has “abandoned all that is fake to obtain the real thing”. What the Box Man actually is and whether the box that acts as shelter, armour, makeshift film lab and portal is anything more than just a literal cardboard box, is an enigma which hangs over the film to the very end.

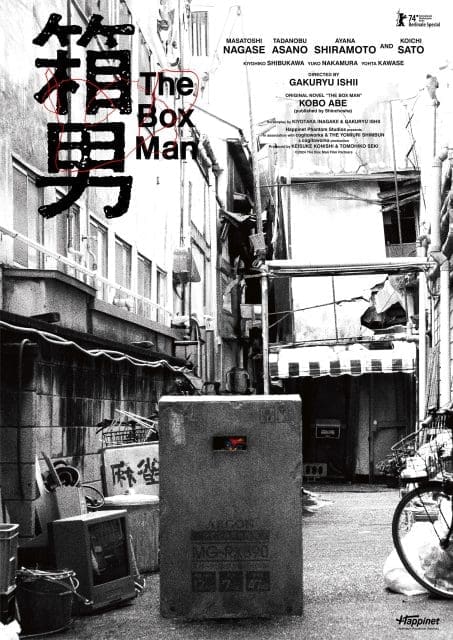

The film, which premiered at the Berlinale in 2024, has had a long twenty-seven year road to final release. Based on the 1973 novel of the same name by playwright and novelist Kobo Abe, director Gakuryu Ishii secured the blessing of Abe to adapt the novel in the 1990s. Work began on the first attempt to make the film in Hamburg, Germany in 1997 before being abandoned. Surprisingly of the original cast remain, including frequent Ishii collaborators such as Masatoshi Nagase (Myself) and Tadanobu Asano (Fake Doctor).

Visually and musically the film is one of tonal extremes, mirroring Ishii’s own back catalogue which is as wildly contrasting as the mediative August in the Water (1995) and the punk film Electric Dragon 80.000 V (2001). Switching from black and white to colour, and from industrial rock to ambient music the film veers from anarchistic to quietly contemplative. Cardboard box-wearing characters and face painted warriors face off in skilfully choreographed scenes reminding me of the mad eccentrics in Shuji Terayama’s films Pastoral: To Die in the Country (1974) and Grass Labyrinth (1979). Ishii’s background as a member of experimental noise band MACH-1.67 is reflected in the way Tokyo is portrayed as buzzing and electric. His characters inhabit a parallel universe, like a surreal city floating on top of the real Tokyo.

Yoko (aka Fake Nurse) is the only significant female character in a film focused on male obsession and desire. But her role is not merely a passive damsel-in-distress.When Myself, the professional photographer who for the majority of the film inhabits the persona of the Box Man, is given the chance to “escape” the box by Yoko, there is a moment where we think they might have a future of real human connection. He rejects this opportunity and instead begins completely covering the windows of the building they’re in with cardboard sheets, creating an even bigger box. Yoko leaves by the back door.

The final sequence traps the audience in a collective sense of peering out at the world through their own cinema screen shaped slit. We’re held trapped for a few minutes in the darkness of the cinema, alone in our fantasy. The Box Man has a universal message for societies which are becoming more individualistic and isolated. There may even be a chance that this stylish and thought-provoking Japanese film about a parallel universe which lives alongside the ‘real one’ gains the kind of traction in the way Parasite (2019) did.

But this is a still film with a provocatively troubling message. This is a film about what happens when people give into the desire of actually enjoying their obsessive, isolated, perhaps even perverted lives. Lives which are always protected and filtered through a screen of some kind. Be it a computer screen, phone screen, tv screen, cinema screen (and on and on). As Ishii himself has said in a recent interview: “We’re all box men now.”