Meeting us on the terrace of London’s Chiltern Firehouse, Sam Taylor-Johnson is in high spirits. The photographer and filmmaker has just wrapped an editing session on her Amy Winehouse biopic, Back To Black, and she seems confident in her process. Hearing her talk about the film, we can’t help but feel it too.

“After reading [the script] I knew we were off on an epic journey,” she tells us. Don’t get us wrong, summarising the life of one of Britain’s most iconic musical legends is a massive undertaking, but if anyone is cut out for the job, it’s Taylor-Johnson. Her first feature, Nowhere Boy, which charted the teenage years of John Lennon, became one of the few musical biopics to stick the landing upon release, wowing audiences and earning the photographer-turned-filmmaker four British Academy Film Award nominations.

Her second feature gained a slight more notoriety than her debut, though it was no less of a box-office smash. Fifty Shades of Grey, an adaptation of the E.L. James’ novel-turned-phenomena, was Taylor-Johnson’s biggest project to date, and quickly became the fourth highest- grossing romantic film of all time.

With Back To Black on the horizon, the photographer, artist and filmmaker talks to A Rabbit’s Foot Editor Charles Finch about her love for the moving and still image alike, her experience working on Fifty Shades, and bringing Amy Winehouse to the big screen.

On Making Fifty Shades of Grey

I was on track to make a film with Sony/Columbia called A Reliable Wife. And it was a brilliant, brilliant script by Andy Kevin Walker who wrote Seven. It was beautifully painful, so I went to pitch it to Columbia and Mike DeLuca. And they both said, “Yes, we’re gonna do this movie.” So I got all sort of geared up—like the sort of inner swell you get when something stirs in your gut.

It came to a grinding halt when the big film coming out that summer didn’t perform. Afterwards all the smaller films got slated and Mike DeLuca said to me, “Don’t worry about it. We’re seeing directors for this film Fifty Shades of Grey. Have you read the book?” I said, “No”. I sped-read it and then went in for this meeting, my agent had said to me, “Use it like it’s practice. It’s good to do these big studio meetings.” I’d never really done one before. I went into the room. I didn’t think it was a real opportunity, or even that I was really going to do it. I didn’t even know if I wanted to do it. I went in and I said: “Look, it’s a fucked up fairy story. That’s how you make it.” And they were like: “Great. Well, can you start next week.” Fifty Shades of Grey was an opportunistic moment. In my head I was like, “Well, I know how to do this. I know what I’m doing. I can distort this book into something powerful and interesting. Because it’s such a phenomenon. I’ll find the core of what that phenomenon means. And I’ll create from that.”

The difficult part was that the author of the book and I didn’t share the same vision.She had a completely different interpretation for how the film should be, it was her book. We had two divided paths which is not the way to make a movie or have a good creative experience.

On Fortune

Fifty Shades was successful, but to me, the success was shadowed by the experience. It took me four years to build my interest in directing again… Money counts for nothing if you feel like what you’ve created isn’t from your soul.

On Inspiration

From a very young age I was obsessed with movies. A lot of films make me cry. It’s that feeling of going into a dark room and being gifted a magical experience. That never left me from when I first sat down in the Streatham Odeon, where they had a Saturday morning Cinema Club. I used to go every Saturday morning and see whatever they were show- ing. I never went with anyone. I’d get on the bus and go on my own, it wasn’t that I was cool, I could never really get anyone else to go. Every- one else wanted to go ice skating.

On Photography

When I left the art school Goldsmiths, I was amongst a big new art moment, Damien Hirst, Gary Hume, Sarah Lucas and all of that group. I had to find my own place within it. I picked up a camera that my cousin gave me. It was a very basic Canon. And from that, I felt like it just spoke to me in such a profoundly different way from anything else. I immediately understood composition and the language of photography. It also gave me a sort of shield in order to be sociable but also hide a little bit. I’ve always kept that.

[The war photographer Don McCullin’s] book was in my school library, in the art photography section and I remember that image of the home- less man with the mouse coming out of his mouth. I thought it was the most extraordinary thing I’d ever seen. And then I went through all his Vietnam pictures and that’s what hooked me onto photography was that very book.

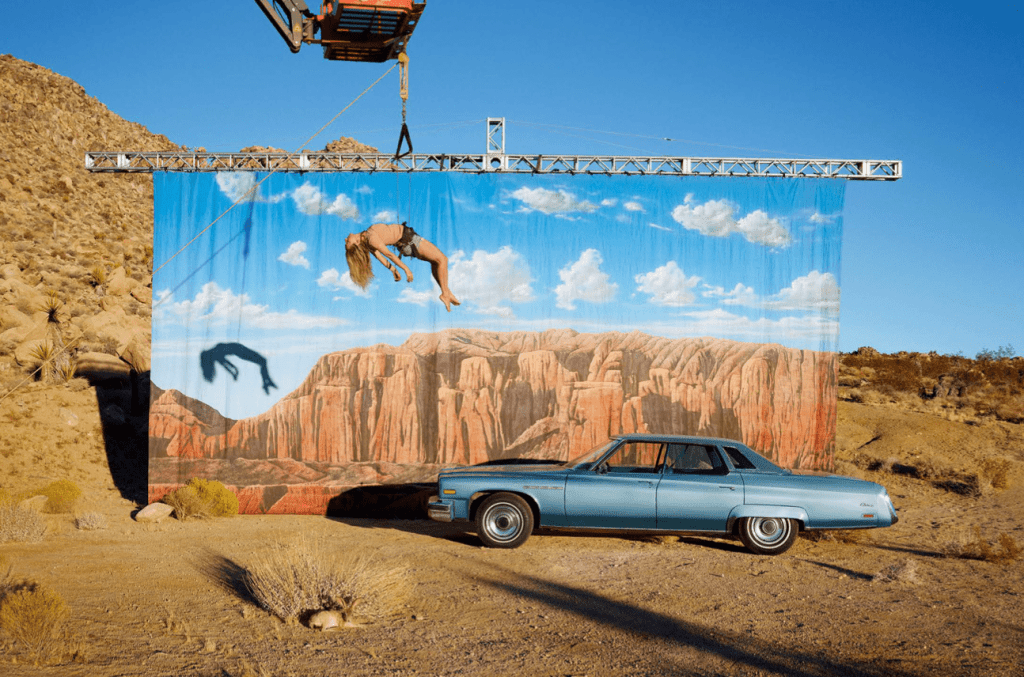

I love photography. I carry my Leica with me everywhere. I try so hard tonot use my phone, which is really difficult. I frame things differently on my phone. When I frame things in my camera, it’s much more thoughtful. With my phone, it’s more immediate. So I try and bring my camera. And I have this beautiful Leica which I carry everywhere. I had a show in Rome about a month ago with Lorcan O’Neill Gallery. It was a series of new self-por- traits of me hanging from cranes in Joshua Tree. It was an intense project that took me about 3 years to realise…It’s like two different brains: film and photography. One takes a massive amount of collaboration and one is very quiet—it needs only me.

On Her Favourite Movies

As a kid, Close Encounters was the first film I loved. The one where you go “ooooh what is this…?” I watched it again recently with my kids and they were all enthralled. I had a stepdad who was obsessed with aliens and UFOs and believed that a UFO flew over our house on the night of Charles and Diana’s wedding. Afterwards he started a whole UFO magazine and then we’d have enthusiasts come round. Our world was a total fantasy world.

I remember when I saw John Carpenter’s The Thing. And then being aware of that sort of new world of fear and hor- ror…but mostly I hate horror.

I have enough real fear in life to deal with, I don’t need more fantasy fear.

Blue is the Warmest Colour is probably one of the best, one of the most profound [erotic] movies. That’s definitely one where you’re like: “Fucking hell, is that really happening?”

Pasolini’s The Gospel According to St. Matthew is such an achingly beautiful film. I think partly because he used all real people, it feels very authentic and those characterful faces and all those soulful eyes…it gives you the time to slowly absorb such a strong atmosphere.

The English Patient. That was one of those movies where you feel the sands shift. It’s one of those movies that affects you on a fundamental DNA level. But that doesn’t happen often. I feel it less and less. I can’t remember a recent movie where I felt that shift. I’ve been watching a lot of early French filmmaking. I kept thinking, I want to create that isolation bubble of love which Godard and others did so well, where the world doesn’t matter. Where they’re a bubble within and away from society. You see everything that’s going on in the world but it doesn’t matter be- cause they’re just desperately in love in their little world. And that’s what I kept referring back to when we were creating my latest film…

On Favourite Filmmakers

Always a tough question to answer in singular terms. A filmmaker may have created just a scene that plays over in my head and then of course there are near perfect movies that hold in your creative thoughts for years. Directors who I am consistently inspired by change depending on what film I’m making or where I am in life. Cassavetes, his film A Wom- an Under the Influence blew my mind as a young avid cinema goer,

he made me want to be a filmmaker. Anthony Minghella was the one who truly encouraged me to be a filmmaker. Jane Campion showed me that there was space for a woman to carve out of the rigid male granite institution in cinema. Paul Thomas Anderson, There Will Be Blood I relent- lessly watch. Other than these 4 instigators the list is long. Most recently, Godard and particularly his film Vivre Sa Vie.

On Back to Black and Amy Winehouse

It’s something that just kicks you in the gut. You either feel it or you don’t and with the upcoming Amy Winehouse film, I read an initial script that didn’t feel right, we rewrote it from scratch. Matt Greenhalgh, who wrote Nowhere Boy, wrote the most beautiful script—achingly beautiful. After reading it, I knew we were off on an epic journey. It was serendipitous. The story is framed by the album Back to Black. It’s the love story that created that album; the love and passion that created it. There was a wild passion between Amy and Blake, her husband at the time. The world stood back and watched this wild, torrid love affair in real time through the paparazzi lens and just commented and judged and ate it up and spat them out.

I watched [Asif Kapadia’s] recent film on Winehouse when that came out and I thought he did a brilliant job. But as I got to know everyone, I thought it’s a perspective too.

I feel like Nowhere Boy, A Million Little Pieces and Back to Black are all very much about the struggle—we are with the protagonist who fights to be themselves against the tide, be it family or addiction. The odds are so heavily stacked against survival, and creatively, what comes out of that time.

On Collaborators

When I read the script, I see the shots and scenes, I then storyboard and hold true to this for the most part. I carry my Leica on set and sometimes

set the frame with shots I’ve taken. I wish I could operate, but it’s a skill I trust to those better at it than me. I’m lucky that I get to work with brilliant cinematographers who can frame and compose shots beautifully and understand how I see the scenes. My closest collaborators are Seamus McGarvey, Jeff Cronenweth and Polly Morgan—the best of the best cine- matographers and collaborators. Matt Greenhalgh for the script, the script and the script. We are on our second movie together and he’s the most in- credible writer and collaborator. I worked with Sarah Greenwood for the first time on Back to Black which was amazing. I love working with these people but film is a massive collaboration with hundreds of people and that’s the fun, the electric energy that goes into putting a story on screen.

On Trusting The Process

I am about to start editing the film I’ve been working on for over a year now. When I am on set, I go into a zone. When I’m shooting a scene, if anyone talks to me or scratches their head, or rustles a bag, I just get really panicked that I’m going to lose the essence of what I’m seeing. I have to be so intensely focused or I fear I’ll lose the precious moment.

You zone in and you zone in and you zone in. I feel like I can see by an eyelash movement whether the scene is going to work or not; if I can see, like, a twinge of something where you can feel that the actors are not in it, then you’ve lost the truth. So if someone disturbs that focus where you’re just in the place, it’s painful. As for filming intimacy and intense emotion,

I don’t find those moments to be particularly tough. I tend to gravitate towards stories that explore both of those as I’m interested in creating portraits of people who have fought and struggled, those moments are part of a whole. The process of filmmaking is tough, getting films made is tough. Being able to work on scenes that are intense or quietly intimate are part of what it is to be human, and that’s what interests me.

Cinema will thrive from us needing a collective experience of story-telling. It’s an ancient art form that will long continue. Content and streaming just doesn’t cut it the same way…