It’s a Wednesday night in Dalston, London and the facade of Molly Blooms, an Irish pub on the Kingsland Road, looks different than usual. Above barbed wire and a spray-painted ‘Free Palestine’ slogan, a banner cobbled together from planks of wood reads ‘The Rutz’. Inside, the clover-green walls are adorned with posters from Irish Republican history. The bathroom’s white tiles are smeared with brown, imitating the ‘dirty strikes’ undertaken by IRA prisoners during The Troubles. By 6pm, a long line of people curls down a rainy side street, eagerly waiting to get inside.

Everyone is here to see the group Kneecap, at an event to promote their album Fine Art, due for release the following day. For the occasion, they’ve transformed the pub into a fictional community boozer reminiscent of the kind you might find on a West Belfast side street. On its third spin—which is followed by a session of trad music and a DJ set—the album is introduced by actor Michael Fassbender. “That was weird as fuck,” says Naoise Ó Cairealláin, one of the band’s members. Irvine Welsh (“the one that wrote Trainspotting”) was also there. “Bizarre, there were all sorts.”

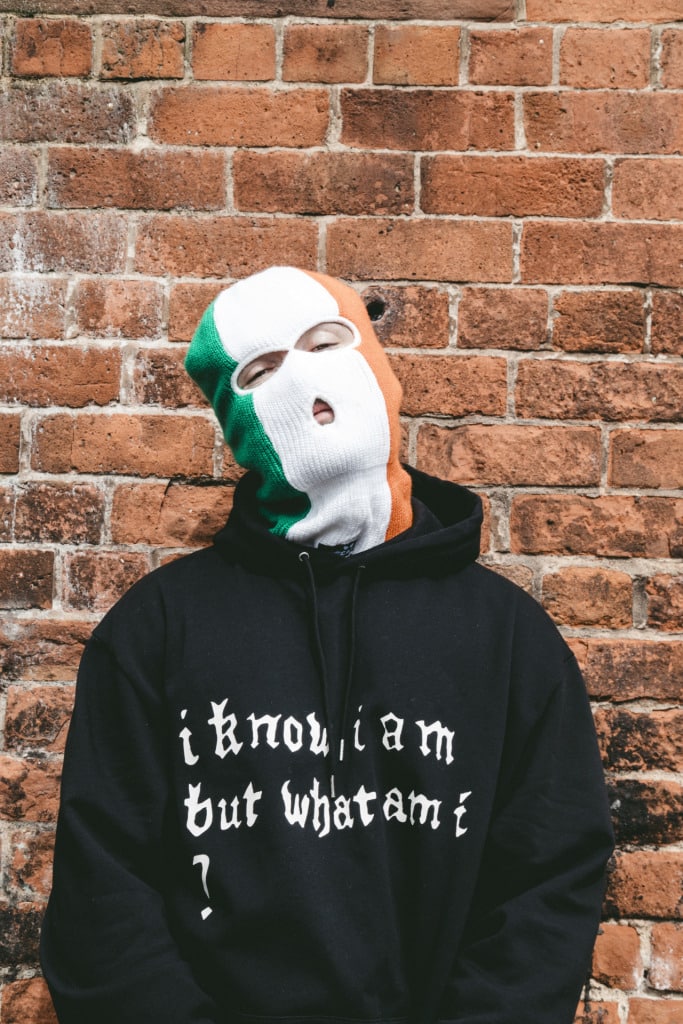

The following day, we meet the group at the Curzon Soho bar, where they’re scheduled for a record signing. Besides Naoise (stage name: Móglaí Bap), Kneecap is comprised of Liam Óg Ó Hannaidh (Mo Chara) and JJ Ó Dochartaigh (DJ Próvaí), who are all native Irish speakers. Unlike the night before, JJ is not wearing his Irish tricolour balaclava. The head garment started out as a practicality: JJ was a teacher and needed to conceal his identity during gigs in which references to drugs were abundant. The silhouette of the head garment has since become a symbol for the group who, through Irish hip hop, advocate for a united Ireland (Tiocfaidh ár lá, ‘Our day will come’, is a Republican phrase repeated throughout their music) and have some good craic in the process.

Kneecap gained popularity with songs like ‘Get Your Brits Out’, ‘C.E.A.R.T.A’ (which translates to “rights”), and ‘H.O.O.D’. The title of their album Fine Art refers to the backlash over their “Farewell to the Union” tour poster featuring former DUP First Minister Arlene Foster and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson strapped to a rocket. “They were outraged, obviously,” says Naoise. “Whenever we were trying to get comments off us, we just said ‘it’s fine art’ and it stuck.” This same response was used to defend their mural in West Belfast featuring a burning police car, which faced accusations of spreading sectarian hatred. “These people are more outraged by a piece of art than by politics and mental health. There’s a fascination with things that don’t matter much,” adds Naoise. “I haven’t seen the DUP address suicide rates. The way they talk about us—I’ve never seen the BBC discuss real issues with such passion.”

“It’s also a reflection on who decides what art is,” says Naoise, referring to the British government’s refusal to grant the band vital arts funding. “They decide what art is, and you can make art only if it aligns politically with what they believe. Art doesn’t take sides; it starts a dialogue.” The controversy and backlash around this decision ultimately boosted ticket sales and popularity. “We were delighted,” says Liam. “The PR was worth more than that £15,000.” “After we wiped away the tears, we didn’t care much,” JJ adds.

“These people are more outraged by a piece of art than by politics and mental health. There’s a fascination with things that don’t matter much…I haven’t seen the DUP address suicide rates. The way they talk about us—I’ve never seen the BBC discuss real issues with such passion.”

Naoise Ó Cairealláin

Fine Art, produced by Toddla T—known for working with Stormzy, AJ Tracey, Roisin Murphy, and Arctic Monkeys—is a concept album set in a fictional pub (The Rutz). Tied together with skits, it stages a night out in all its highs and lows. The euphoric opening track ‘3CAG’—short for 3 Chonsan Agus Guta, ‘Three consonants and a vowel’ (aka MDMA), featuring vocals by Lankum’s Radie Peat, kicks off the evening. ‘Love Making’ is a bass-heavy track about a one-night stand. In ‘Harrow Road,’ they land in London. ‘Parful’ samples ‘Dancing on Narrow Ground,’ a BBC documentary about Protestant and Catholic youths dancing across the divide. “It resonated with us. We just want to put people in a sweaty room with a drink and some ecstasy. I don’t think young people care about politics, really,” says Naoise.

The energy of Kneecap’s live sets is captured in the recordings. “What’s the word? High octane,” says Naoise. “Your English is very good,” jokes Liam. “When you go to our gigs, it’s a whole journey,” says JJ. More minor key tracks include ‘Sick in the Head,’ reflecting on the high cost of mental health services compared to drugs, ‘Better Way to Live,’ featuring Grian Chatten of Fontaines DC, exploring a more downbeat cycle of hedonism, and ‘Rhino Ket’: “Can’t sit, can’t think, can barely even walk/Dunno how the fuck we’ll make it back to the Falls.”

“We like to acknowledge that there’s a high and also a low. You have to come down nicely,” says JJ.

In 2019, filmmaker Rich Peppiatt walked into a bar on the Falls Road in West Belfast. Having recently moved to the city with his wife, his interest was piqued by a poster for an Irish Hip Hop concert at Limelight. Inside, he found Kneecap performing to a packed crowd. “There were probably about 800 people in there,” he says via Zoom. “I knew Kneecap were rapping in Irish, which was interesting. But what was more surprising was that 800 people were rapping back in Irish—I didn’t realise there were that many young people in Belfast who understood Irish. I thought it was a language confined to the countryside and old people. As a filmmaker, I thought if I don’t know this, there must be millions who don’t either. It was the start of something interesting; the foundation of what potentially could be a story.”

Peppiatt contacted the band and began meeting them casually to develop the story. He decided on a biopic narrative feature, creating a mythology of the band with a truth that is greater than fiction. “Every fuckin’ story about Belfast start like this,” opens the film in a narration by Liam, with a montage of archive footage of explosions. “But not this one.” It starts instead, with the baptism of Naoise as a “wee baby” in a forest, which is interrupted when the police think they’ve uncovered a secret IRA camp. The film jumps forward as the three start to make music together. JJ, a music and Irish language teacher, interprets for Liam when he refuses to speak English to the police. Noticing some lyrics in his notebook, JJ says they can use their studio, leading to the formation of an Irish rap group. “What is Belfast known for? George Best, Titanic, kneecappings.”

The film portrays the Irish language as a form of resistance. “Every word of Irish spoken is a bullet fired for Irish freedom,” says Naoise’s father, Arlo, played by Michael Fassbender. Fassbender’s previous role as hunger striker Bobby Sands in Steve McQueen’s Hunger made him a fitting choice, but it was also a practicality. “There are only a handful of top-tier Irish actors who speak Irish,” says Peppiatt. Despite his role being a cameo (“I read one review that said they got Michael Fassbender and barely used him. How arrogant,” says Peppiatt), the actor “raised everyone’s game.” Naoise, Liam, and JJ enrolled in extensive acting lessons. “We went two months without any drink. Then we got to the hotel the night before filming and got pissed—the whole first day of filming we were all hungover.”

The writing process was a close collaboration between Peppiatt and the band. “From the start, I said to the lads that it’s not my story to tell,” says Peppiatt. The band consulted on script details and structural questions. “They were like, none of us can be the lead character—we all equally need to be the lead. Do you know how fucking hard it is to write a film with three protagonists?” In their interviews, the band and Peppiatt gently slag each other off, in a way that signifies deep fondness. “Still don’t trust him,” says Liam about working with an Englishman. “He’s got 11 toes,” adds JJ. “They have this annoying ability that they don’t seem to try, and it just works out really well for them,” says Peppiatt. The band’s relationship with Peppiatt is like that towards a slightly more sensible older brother. “It’s always very difficult doing red carpet things because what do you wear when you have to stand next to three blokes in a tracksuit?”, says the director.

800 people were rapping back in Irish—I didn’t realise there were that many young people in Belfast who understood Irish. I thought it was a language confined to the countryside and old people. As a filmmaker, I thought if I don’t know this, there must be millions who don’t either. It was the start of something interesting.”

Rich Peppiatt

Peppiatt and Kneecap wanted to redefine what an Irish language film could be. “They’re always set in the past. It’s always the potato famine,” says Peppiatt. “We thought, wouldn’t it be cool to make a film for Irish speakers that was modern and gritty and blackly comic—sex and drugs.” Trainspotting was a key reference, not only for its depiction of hedonism but for its temporal and geographic specificity. “When it was made, people were like ‘why make a film about Edinburgh skags?’” Kneecap, like Trainspotting, is filled with colloquial language, from ‘peelers’ (police) to ‘taig’ (a Catholic). “Even as the film got bigger and more money came in, the mission stayed the same. This had to represent West Belfast in 2019.”

The specificity paid off. The film was an instant hit at the Sundance Film Festival. “They laugh at totally different jokes,” says Naoise. “Obviously they do, they’re Americans,” adds JJ. Many Americans are now trying to learn Irish. “Too many. It’s not going to be a minority language anymore,” says Liam. “We’re not going to have our niche.” With Kneecap, four stars are born: Naoise, Liam, JJ, and Peppiatt. “We joke about who invented who,” says the director, who is now working on his second feature. “There’s no band in existence who, at the same time as their debut album, have had a mainstream feature film coming out distributed around the world. It’s a rocket ship of a launch pad, because right now, most people don’t know who Kneecap are.”

On the Falls Road in West Belfast sits the Cultúrlann McAdam Ó Fiaich, an Irish language cultural centre. It is here that Kneecap suggest we meet for their photo shoot—it is where they did all the acting classes and writing sessions for the film. Fresh from Glastonbury (Kneecap performed twice, though controversially, none of the performances were aired by the BBC), only Naoise and Liam are in attendance. As JJ has a new born child, DJ Próvaí’s balclava-clad role is taken for the day by Peadar ó Goill, the band’s photographer and friend. Inside and outside the centre, they are constantly stopped by passersby. The postman chats with them. A man abruptly parks his car in the street to get a selfie for his son. Inside, a group of ladies ask for a photo with the young musicians. “No, no. Mine was black,” says one lady cheekily, when offered the balaclava.

Even as Kneecap’s success grows, this area of West Belfast will always be their heartland. While they list dream collaborators—“Amyl and The Sniffers, Jay Z, Roy Keane, Christy Moore, Robert De Niro from Shark Tale”—for Kneecap, fame will never come at the cost of integrity. “In a world where everything feels PR-ed and packaged, and celebrities are scared to say anything controversial, Kneecap would rather stand for their principles and disappear tomorrow than compromise. If they never played a gig again because they supported Gaza, that’s fine. It comes from a political place but also just being decent human beings,” says Peppiatt. “And hopefully, as they get bigger, they won’t turn into assholes.”

Kneecap is in cinemas in the USA from 2nd August, in cinemas on the island of Ireland from 8 August, and England, Scotland and Wales from 23 August.

Photography by Macy Stewart. Creative direction by Broadpeak Studio, styling by Anna Pierce, hair and make up by Shaia Hassay. Clothes courtesy of Robyn Lynch and CELINE.