In 1973, Brassaï was seventy-four years old and known worldwide by his one, self invented name, master of an extraordinarily original body of work, photographic, sculptural and literary, amounting to a holy grail revered and cited as an inspiration by a host of photographers as accomplished and original themselves as Diane Arbus, Helmut Newton, David Bailey and Bill Brandt. Picasso had called Brassaï’s drawings and sketches a goldmine, and they’d collaborated on all manner of projects since the 1930s. Henry Miller had anointed Brassaï, “The Eye of Paris” – a title much accepted and quoted even at Brassaï’s landmark MoMA NY exhibition.

In 1973, I was nineteen years old and a tad hopeless, having muddled through a sequence of secondary schools, yet instinctively contrarian, headstrong, determined with an instinct for portrait photography. I was driving across the country in a 1964 VW with no precise plan, no means of support, but determined to find my way. Determined not to head for Harvard for which I’d been predestined by an egregiously exigent Harvard-Rhodes-Scholar-Oxford-doctorate father who’d dressed me in ‘Harvard Class of ??’ t-shirts in infancy. By now, he’d been rendered an apoplectic academic with a seriously dim view of my ‘determinations’. Were I not to follow his heavy footprints he presented an alternative in his refrain: “You haven’t got a mothball’s chance in a public urinal.”

I did love and admire my father and his turns of phrase. Broke in Boulder, Colorado, I turned the VW around and headed for the safe haven of Harvard summer school. I’d sought safe haven in otherworldly worlds—even dangerous ones felt safer than the hapless confines of a public urinal. Mind altering drugs guided by readings of Aldous Huxley, led to a fascination with Surrealism, the humor and wit of Dada and Duchamp, hence Warhol, (and in time, assignments for Interview magazine).

At Harvard summer school, I was drawn to a post-graduate course, taught in French, on the Surrealist and Dadaist movements. I hadn’t much more than a fine grammar school education and faded grammar school French to match: no qualification for admission to this most advanced class beyond an honest intrigue with the curriculum, a fond sense of the halcyon years between the wars in Paris and a vague affinity for André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto and the fancy Minotaure magazine. Somehow, I passed the required interview with the erudite Professor John L. Brown who took an eccentric chance on me. And so began a sybaritic Summer in Cambridge of sailing small boats on the Charles River and attendance at Mr. Brown’s class and for good measure, some anthropology classes. I wondered whether Harvard weren’t so bad, but greater need was for safe haven from the apoplectic academic; Harvard felt to become an arena, his arena.

Come the fall, once again worried by the specter of the mothball, I remembered that my father had spent years at work on his doctoral thesis; so I explained to him that I had a ‘thesis’ to write for the great Professor Brown at Harvard. Holed up alone for an idyllic if melancholy September and October in Southampton, I did write, and I chose to write about Brassaï, who had not been much part of Professor Brown’s curriculum but whose work intrigued me no end. Brassaï, an individualist, never part of any movement, was no Surrealist per say (as was Man Ray), yet I found surreal tones in his photographs and titled my paper, Brassaï and Surrealism / Brassaï as Surrealist. He seemed to inhabit a world of his

own mystery, imagination and invention which he documented in photographs. My ‘thesis’ elaborated on specific photographs and their dream-like qualities whether the foggy, strobe-lit night images—buoys in the Seine that appeared as birds, or the stark portraits – Matisse in front of a big sketch Brassaï had whimsically asked him to make blindfolded. The sketch resembled a Picasso. (I read my paper now and wonder at the delirious imagination of the kid who wrote it.)

Finally, in February of 1974, I mailed my paper, in English, to Professor Brown who returned it with some critical markings and a formal not informing that the paper, six months late, had been due in August, and in French, and so I’d flunked. He was perplexed as to why I’d bothered to submit it at all but conceded that my treatise might be of interest to an acquaintance of his: Brassaï himself. Professor Brown provided an address on the rue du Faubourg St. Jacques, 14th arrondissement, Paris.

In April of 1974, an enthusiastic, page-long, typewritten letter from Brassaï with his handwritten notes arrived from Paris. It began saying that my piece had given him ‘une grande satisfaction’ [red underlined] and a few lines later, the sentence that altered my perception of myself, forever: “You have well understood and expressed the spirit in which I made my photographs.” Brassaï embellished: “Jean Giono said to me one day: “Reality pushed to the extreme, leads to unreality. To go straight to things is to accept their magic…” I too think that the sincere and humble pursuit of the most everyday reality leads imperceptibly to the fantastic. And the change of scenery takes place without our noticing it. Also, I never looked for the exotic or sensational in subjects. Most of the time, I drew from the daily life around me. (…) Starting from the most everyday reality to arrive at the surreal, such was my goal, my preoccupation, my experience in the matter of photography…”

Brassaï’s letter was a saving grace: I felt redemption, validation of my thoughts and by extension, my very existence. I felt I could die now: I’d done something. I was somebody.

My father, a drama critic and classic film distributor, was impressed and arranged an attic maid’s room for me in the 8th arrondissement a tiny, tidy 6th floor walk-up recently vacated by Jean-Pierre Leaud and belonging to François Truffaut’s offices. I could stay indefinitely. I did feel bidden a hail-mary-good riddance, but I was delighted to be able to write back to Brassaï that I just happened I’d be coming to Paris. I was told to be in touch on arrival and was subsequently invited for lunch.

On the appointed day in November, I rode the minute elevator up the center of the stairwell to the 4th floor apartment Brassaï had inhabited since soon after the building was constructed in 1932, the year of his first successes and his first book of photographs, Paris de Nuit. Mme. Brassaï, Gilberte, flustered and nervous at the front door, explained that a visiting art collector was presently overstaying his welcome. I was to take a walk and come back in half an hour. I wandered the quartier and recognized traces of the Montparnasse Brassaï had photographed nearly half a century ago, along the external walls of La Santé prison down the Blvd. Arago and back to Brassaï’s on the Faubourg St. Jacques where an elegant baby carriage had appeared, parked in the entrance lobby. I felt it had

significance. I photographed it. Gilberte met me at the door again with impatience—the collector was still deliberating. She ushered me into the parlor where Brassaï was sitting on a sofa next to the fastidious expert, a highly groomed man in a three piece suit, a stick-pin in his tie. The floor was strewn with dozens of exquisite, shiny, ferrotype prints. A strikingly huge, dark, woven wool tapestry composed by Brassaï from his photographs of graffiti covered an entire wall. I was introduced and told to sit next to Brassaï on the sofa where he received me with disarmingly instant charm that felt familial and confidential. He seemed just as relieved with my fresh presence as he was frustrated with the collector. Shortly, Brassaï stood up to the sound of crackling prints under the shuffle of his pantoufle slippers and marched out of the room in exasperation. The collector shrieked and, on his way out, could be heard berating Brassaï as a ‘fou’ to Gilberte.

Brassaï came back to the sofa and chuckled with an amusement I grew to love. Mischief. And then he confided, “My friends are all dead.” Most of Brassaï’s friends had been older. Picasso, his faithful pal since long before and during the war had died just the year before at ninety-one. Brassaï was now seventy-five. I’d already felt familiar with him: his humor, mystery and melancholy matched the man who had expressed himself powerfully, with visual and literary articulation in photographs, prose and poetry, drawing and sculpture. Brassaï’s one brief foray in cinema, “Tant qu’il y aura des bêtes” had won the prize for originality at the Cannes Festival in 1956: an hilarious and moving short, a personifying study of zoo animals and their quasi-human habits: humour, mystery and melancholy. (Brassaï commented, “My 22 minutes were long enough in the movie business!”) We three went and had a robust lunch on the Place Denfert-Rochereau. His spirits vacillated up, low, and then a laugh. He was writing brilliant biographies—one on his hero, Proust and two that were in the form of participatory biographies on his colleagues Picasso and Henry Miller: narratives in which Brassaï himself figured.

Brassaï had had a big show in New York presented by John Szarkowski at MoMA in 1968. (I’d used the catalogue as principal reference in my ‘thesis’.) But of late, he’d had difficulty publishing a particular book of his photographs. He’d organized boxes of meticulously edited prints labelled and titled for books and exhibitions, and he’d sent priceless binders full of two hundred special prints to an agent in New York: photographs from the early 1930s considered too risqué to publish while the subjects were alive (madams, prostitutes and johns, nudity and opium dens). This trove of prints languished in New York—with no interest or response from the agent.

My beloved friend and sometimes surrogate mother, Elaine, of Elaine’s restaurant, had sent me a Christmas card folded over three crisp hundred-dollar bills. The note read, ‘Take Icelandic, there’s a dollar left for cigarettes.’ So, I was going home for Christmas, and Brassaï asked if I might somehow recuperate his prints and get them back to Paris. I did—with a nocturnal stop at Elaine’s where George Plimpton and other denizens raved in amazement over the two big binders as if discovering the lost time in Paris they’d always sought. Once safely back in Brassaï’s hands, the prints became the book soon published by Gallimard to triumphant acclaim: The Secret Paris of the 1930s. How proud I was to have been able to help and for Brassaï’s gratitude.

I stayed in Paris for exactly an impecunious year until the very last flight by which my return ticket expired. I saw Brassaï regularly, deriving infinite encouragement from his direct comments on my own photographs and his sympathies and amusement as I eked sustenance, a subsistence, hustling at backgammon after midnight in nightclubs on the rue de Ponthieu. More reputably, I contracted a stint as the very first Paris-based photographer correspondent for the fledgling W magazine.

Back in New York for a difficult spell, I attempted to concoct a book—to be titled ‘Elaine’s Kitchen’—of my portraits, done in the restaurant’s fluorescent-lit kitchen, of illustrious patrons. My attempt was aborted. Elaine handed me an un payable bill for $500 in spaghetti I’d shared with her over backgammon. Another year had passed, and the window for my matriculating at Harvard closed while I’d been distracted: lost in the shuffle of dice and heaps of wee-hours spaghetti. Feeling exiled, I got back in the old VW and drove as far as I could, to Los Angeles. I stayed in touch with Brassaï. He wrote letters of recommendation for grants I never quite got and kept me posted on his Secret Paris book tour and glamorous reception at the Marlborough gallery in New York. At my insistence, he and Gilberte went up to Elaine’s where they were fêted on the house. LA wasn’t all palm trees, sailing adventures to Catalina and movie premieres. I worked moving boxes and all sorts of unmentionably sordid jobs—got my hands awfully dirty. I took occasional magazine assignments, some of those, unmentionable, too.

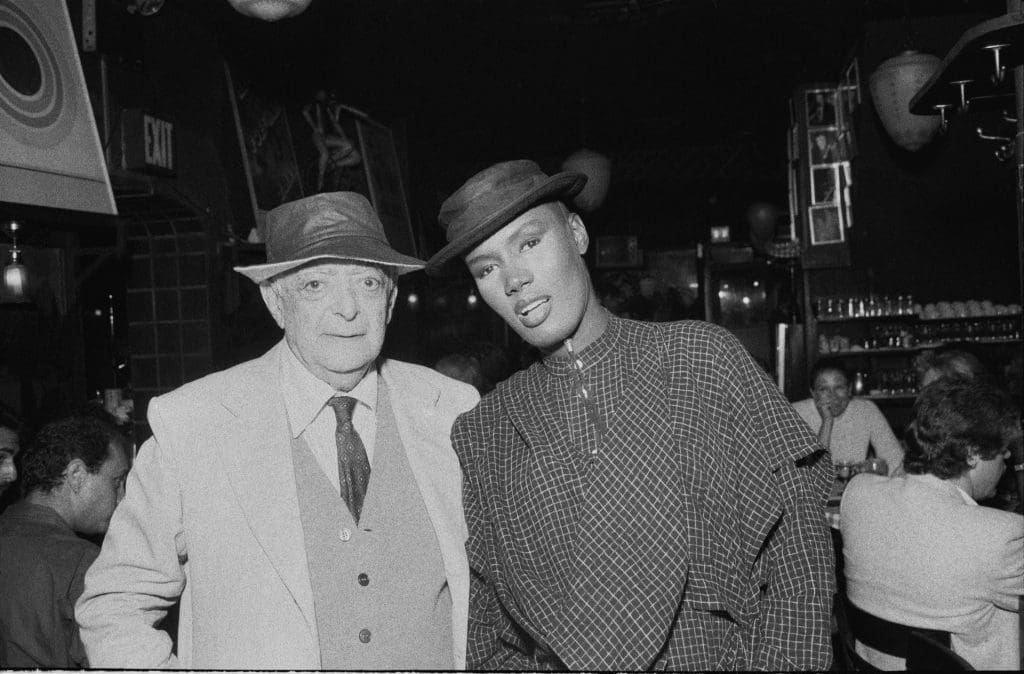

Three years later, in 1979, I’d flown definitively back to New York in fear of becoming an actual Californian and found myself at the night shift helm of a Checker cab for a few years. It wasn’t Harvard; it was an education from which I did graduate. Brassaï arrived in New York for the heralded launch of his masterpiece new book—The Artists of My Life—and yet another huge Marlborough show: myriad portraits of virtually all the important artists of his day in their elements and with details of their studios and work including Maillol, Picasso, Bonnard, Braque, Matisse, Giacometti, Miro, Kokoschka and Dali. It was September, and the 9th was his 80th birthday; we had dinner at Elaine’s for six: Gilberte, Jean-Paul Goude, Grace Jones, Elaine, Brassaï and me. Brassaï presented an elated Elaine with an inscribed poster for the exhibition: a 1939 portrait of Picasso with an enormous heat stove in his atelier on the rue des Grands Augustins. It went up over the end of the bar where Elaine sat conjuring her bills every night, and there it hung for the next thirty-three years.

Brassaï felt something about 1970s New York and Elaine as analogous to Paris between the wars: model, romantic years for Elaine and for many of the writers, her patrons, who’d founded The Paris Review in the 1950s: the same group Brassaï had photographed in their youth on a spiral staircase in post-war Paris. In that 1970s New York, Phillipe Petit sauntered into Elaine’s after his high wire crossing between the World Trade Towers to the cheers of writers, filmmakers, producers, musicians, sports figures, theatre people, theatre patrons in black tie after an opening, artists, editors, even poets of remote renown who enjoyed an exuberant status of their own. Elaine sat at the epicenter, where the status was celebrated and conferred in coveted table assignments. On Brassaï, Elaine lavished pure veneration. To help publicize his artists book and exhibition, I endeavored to interview Brassaï and photograph his portrait for Bob Colacello at Interview magazine. On a weekend in Southampton, Brassaï insisted on re editing the interview—questions and answers both. He went up to his room and typed all night on my little Olivetti. I contributed an opening question, “As a child in Transylvania, weren’t you afraid of Count Dracula?” His answer: “No. Murnau’s Nosferatu [the silent movie that made Dracula famous] hadn’t been made until 1922. Doubtless he was there, but no-one had yet heard of Count Dracula.”

Brassaï was amused by the association anyway. Dracula had become the Transylvanian even more widely known for his nighttime forays than Brassaï. In New York, at the MoMA reception for Ansel Adams, Brassaï was being photographed and two young girls approached and asked him who he was. “I am Dracula.”

In 1981, for Vanity Fair magazine, which had been published from 1913 to 1936, a much anticipated re launch was in the works. Jean-Paul Goude had introduced me to Bea Feitler, an infinitely talented art director, who had taken me under her wing and was designing the new Vanity Fair prototype. Bea built two features and a ‘front of book’ piece around my archival portraits. One, a portrait of Brassaï, served to introduce a portfolio of Brassaï’s artists’ portraits laid out ingeniously, juxtaposed to those artists’ respective works. Brassaï adored the layout as well as being in the new magazine’s limelight. Bea had been the protégé of Marvin Israel at Harper’s Bazaar where Brassaï himself had worked on myriad assignments for the primordial and seminal art director Alexei Brodovich and his editor, Carmel Snow. Those assignments included the artists’ portraits Bea had laid out. A circle completed. Brassaï took vicarious pleasure in my assignments for Vanity Fair. We commiserated about the inevitable difference between editors’ assignment concepts and the reality of what one eventually delivered for a portrait or a story. I was learning.

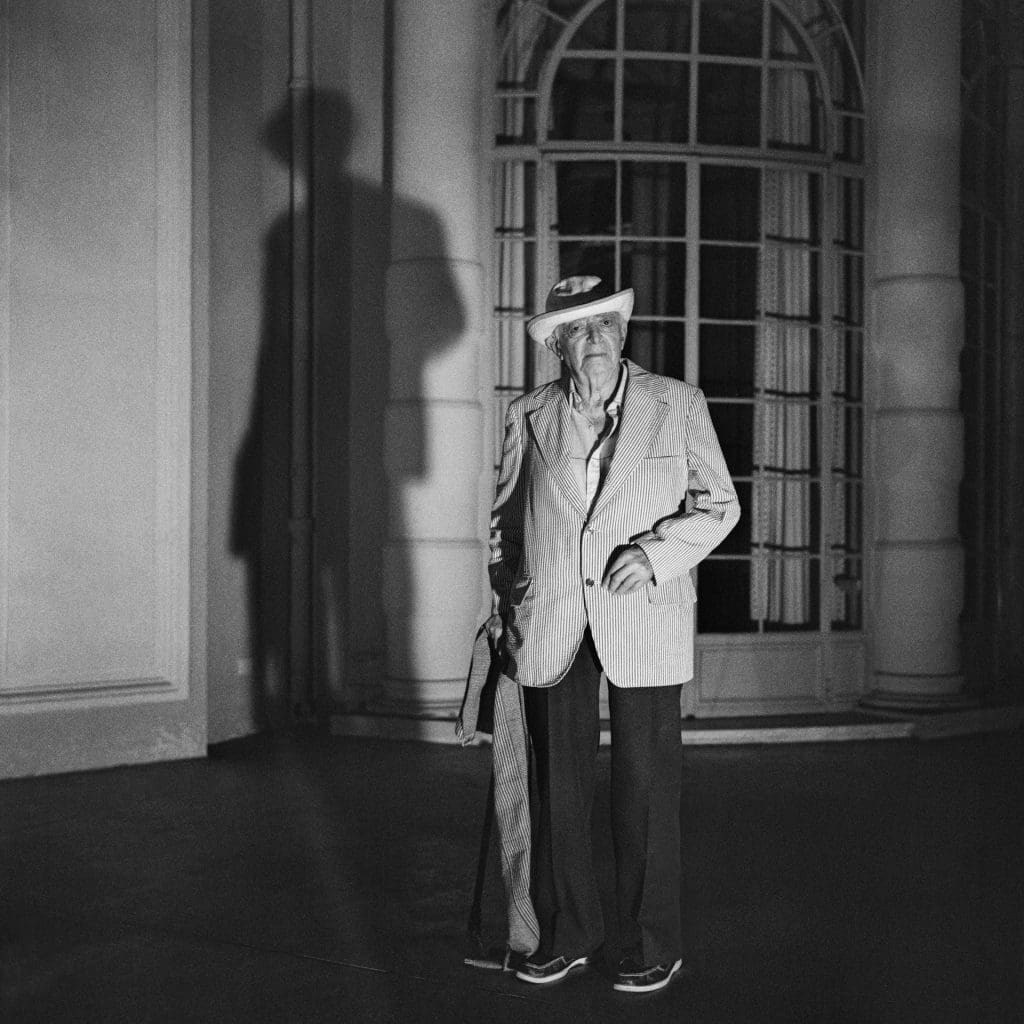

In May and June of 1982, I went to visit Brassaï in Beaulieu and Èze. On a lunch trip to Monte Carlo, we stopped at a newsstand for the new copy of Life magazine, which Brassaï opened to find a pin-sharp close-up on a double-page spread of his own eye by John Loengard. The image provided a moment of surreal surprise and amusement; Brassaï, Henry Miller’s very ‘Eye of Paris’, was confronted starkly with his own gigantic eye. Brassaï was a ‘noctambulist’ in the literal sense of one who ambles at night. That inclination had led to his initial use of photography to record what amazed him in the dark and to his first book, Paris de Nuit, in 1932. In early July of 1984, at the end of another extended visit in Beaulieu, we had dinner down in the port on the terrace of the African Queen restaurant. Brassaï’s big eyes literally spat tears of laughter at reminiscences of once insurmountable difficulties and desperate measures. We talked about the little fires he’d built, absent a fireplace, in the middle of his Paris apartment to stay warm during the war. The oak floor still showed char in places. Later that night, we went for a stroll around town, and I photographed Brassaï noctambulating for what turned out to be his last time. The next morning, I went up to Paris where I got news, few days later, that Brassaï’s failing heart had given out.

The summer after Brassaï died, while visiting a grief-stricken Gilberte in Beaulieu, I stayed nearby at a gloriously simple hotel atop Cap Ferrat where I invited Helmut Newton and his wife, June, to come over from Monaco for a small dinner with Gilberte. Brassaï and Helmut had had jovial relations. Brassaï had once played a comical role in a series of Helmut’s photographs, but Gilberte had often kept Helmut at a distance. She felt him competitive and stressful. In condolence, at dinner, Helmut was emotional and explained how Brassaï had inspired and motivated him. Gilberte was deeply moved. So was I. Helmut said he envied my communion with Brassaï. It often comes home to roost how very privileged and extraordinary was our rapport. I’m endlessly grateful. In 1999, enroute to the opening of the Brassaï retrospective at The National Gallery, I watched Irving Penn travel alone, in silence. We happened to board the same train car in New York to Washington, D.C. I didn’t yet know Penn; I didn’t introduce myself. He hailed a cab to the Gallery, where he talked to no one and went directly to the photographs and stood and studied each print, one-by-one, with meditative reverence. Such was his intensity of focus that no one approached him: two hours, oblivious to the social carryings-on and the opening’s formalities. When done, he walked a brisk bee-line for the door, back down the steps to hail another taxi back to the train, straight back to New York. Pure homage.

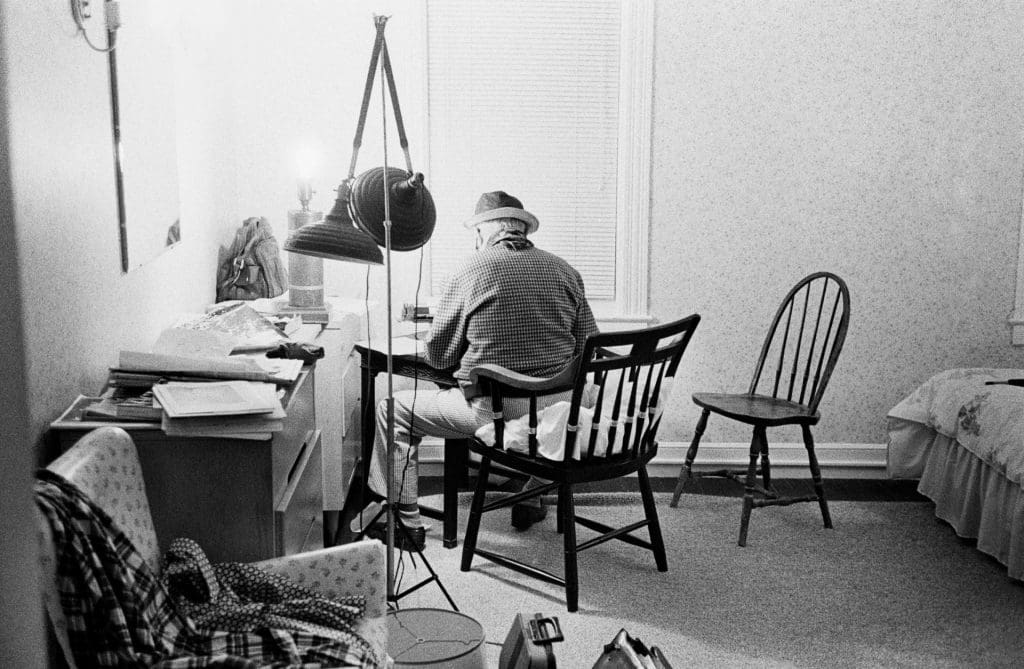

As Brassaï had gotten older, privacy, always a distinct priority, became paramount. He was content in devotion to his writing and his archive. Major museum shows threatened to cause anxiety and to take time. While Gilberte became a gatekeeper known to irritated gallerists and curators as ‘Madame Quidit-Non’, Brassaï’s door had always opened for me. Following Brassaï’s wishes and her own instincts, Gilberte gave her remaining twenty years to putting the photographs, drawings, sculptures and tapestries in impeccable order with the help of archivist Stuart Alexander and managed unimaginable success: retrospectives at the Pompidou and capital cities worldwide, generous donations and legacies to the French and international museums. She arranged her devoted nephew, Philippe Ribeyrolles, to succeed her. In collaboration with Philippe, Peter Galassi, Szarkowski’s successor as Director of Photography at MoMA, and now an independent curator, has produced a definitive, all-encompassing and scholarly work titled, simply, Brassaï. Of Brassaï’s biography, Conversations with Picasso, Picasso said, “If you want to know about me, read Brassaï’s book.” For Brassaï, the same might be said of Galassi’s tome. I’ve had magazine and commissioned portrait work galore, museum retrospectives and books of my own, even an honorary doctorate, not exactly golden showers, but hat off to my father: it was on that Harvard campus that seeds were planted for a most transformative rapport. I do forever miss Brassaï and Gilberte: their humor, and sense of scale and historical proportion that have put challenges in perspective, by example, and guided, leavened and enlightened my way.