Neo-Tokyo. It’s a post-war setting that’s almost on the nose for the $1bn Yen movie adaptation of Akira—the anime classic directed by its own mangaka Katsushiro Otomo. When a science experiment goes wrong and wipes out Tokyo in an explosion, a new, brighter city grows from the crater. Drugged up, roughed up and forgotten by their peers, Otomo’s twin heroes, Kaneda and Tetsuo, live as biker vagrants in this new city’s underbelly, racing the streets like blurs of uncontrolled lightning. Pioneering the cyberpunk genre, Otomo immerses his souped-up cafe racers in military experiments, Shinto worship (for those following the manga), anarchy, and a dose of ESP-induced teen angst. While the movie would take the West by storm, what’s often overlooked by foreign viewers is that its boiler-suit wearing motorbiking protagonists are inspired by a real youth movement: the bosozoku.

It’s a shame. Without bosozoku, Akira may as well be based on unicycles. Always darkening his childhood diet of cute sci-fi manga (which, like Atom, was ostensibly obsessed with atomic destruction), Otomo yearned for a hard science fiction that could balance social realism with his imaginative flights of fancy. Taking cues from Moebius and realistic perspectives rather than anime’s older Disneyland aesthetic, Otomo was one of the first mangaka to draw lifelike Asian characters. The bosozoku are part of that process: characters lifted from an adrenaline-seeking youth culture that was furious at a post-war Japan moving too fast to catch up with.

Two bombs level two different cities, leaving behind a charred crater in each wake. This isn’t Akira’s central narrative structure, but 1946 Japan. Threatened with out and out nuclear annihilation by America, Imperial Japan surrenders, admits its emperor has no god-given powers, and orders its soldiers home.

For the kamikaze pilots ready to fly themselves to certain death, the retreat was a bitter pill to swallow. Under the auspices of a hopefully benign American protectorate, an unlikely subculture of misfits spawned from its WWII veterans. Mixing samurai bushido spirit with nods to an American greaser boy rebellion, the bosozoku bicycle gangs emerged. Spawned by suicidal pilots and soldiers without a war to return to, customised motorcycles, crime and drag racing became their next best fix.

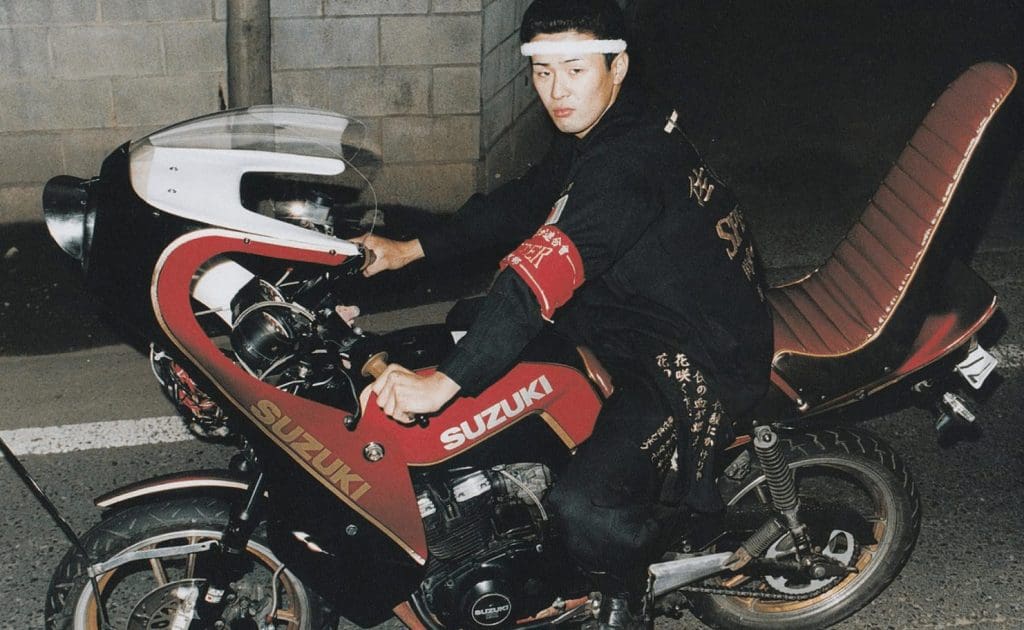

By the time the 80’s rolled around, a futuristic Japan had emerged from the ashes of its old war aesthetic. Despite the prosperity, old ways, groups and identities had become strained; and the disconnect took a distinctive Japanese style. Inheriting the biker’s kamikaze spirit, teenagers with access to cheap dirt bikes surged the bosozoku movement to a small militia of 40,000 young men and women. Operating in distinctive groups, their old-war boiler suits—tokkofuku garbs known as ‘attack uniforms’—were complete with lead pipes for fights, pomades, headbands and surgical masks. Teens would ride illegally modified vehicles with garish insignias, flags, fluorescent bodykits, raised seats and mufflers. And as they rallied down Japan’s expressways, vandalising cars and poll stations along the way, their muffled bike engines would echo like thunder along the busy streets.

There’s a right-wing pride for an old Japan in their rallies, while the vandalism echoes the nihilism seen in Akira‘s most apocalyptic scenes of self-destruction. Run largely by adolescents who had dropped out of the social system, the biker-bushido spirit has a youthful camaraderie that wouldn’t be out of place among Kaneda’s eccentric gang of delinquents. Admitting the irony of a group of dropouts who didn’t give a damn about school finding meaning, one living biker admits, “My friends and I would spend days together, racking our brains and trying to come up with poems we wanted written on our tokkofuku.” It’s an odd tribe: mottos could range from gratitude for teachers putting up with their poor behavior and love letters written next to gang signs and fascist samurai phrases ‘Shichisho hokoku’ (Live your life seven times in dedication to your country).

Maybe it’s that tough exterior, vulnerability, and a rush of petrol-headed adrenaline that inspired Otomo’s cyberpunk protagonists. Or perhaps it’s that these samurai-inspired racers feel left behind by the world—like so many characters in Akira. More than the style (just look at the rival ‘Clown Gang’ and ‘The Capsules’ outfits), the contrast between man and machine like drove Otomo’s interest in the sub-culture. “Amoebas [the source Akira’s psychic power] don’t make bombs or motorbikes,” warns Kaneda’s love-interest, “they just eat.” Brimming with Shinto worship, drum rolls and psychic energy, an older, more spiritual Japan lives under Akira’s sprawling metropolis: threatening a city that’s been paved over by an adult world of machines, warfare and technology. The twin identities are doomed to destroy each other, time after time—and the antagonistic bosozoku who straddle the line between East and West, new and old, are the ideal drawing board for that rebellion.

Blurring together fantasy and reality, Otomo’s nod to the bosozoku’s discontent exaggerates a future that hasn’t gotten better, but darker. Fuelled by a nuclear powered fear for what miracle or curse science might bring next, the relentless pace of technology is Otomo’s core motif—and Kaneda and his 200 horsepower vehicle might be a motorist’s wet dream for escaping a city built over its own ashes. In the underbelly of that bright new world, when Tetsuo steals Kaneda’s keys, his options are pure bosozoku: drive somewhere, anywhere, that’s not here—or burn the whole place down.