It’s hard to understand, given the success of Angela Carter and Raymond Carver, why Rachel Ingalls isn’t in the rock and roll hall of literary fame. Ingalls herself suggested it was the “very odd, unsalable length” of her novellas. Across her eleven collections and stories, her gimlet eye skewers a range of themes but it’s love, sex and passion that sit at the heart of her glittering tales.

Who is Rachel Ingalls? Only shards of information about her private life are known. Born in Boston in 1940 (her father was a professor of Sanskrit at Harvard), Ingalls dropped out of school and studied in Germany before winning a place at Radcliffe College. Shakespeare’s quadricentennial drew her to London and in 1965 she came for good, living in North London until her death aged 78 in 2019.

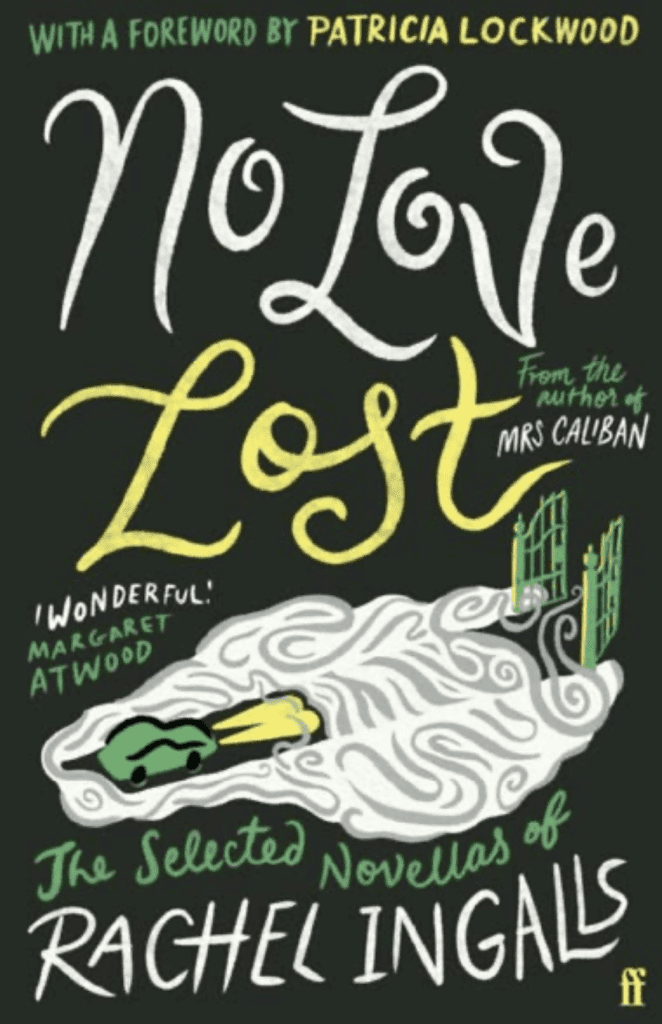

John Updike reviewed Mrs Caliban (her 1982 tale of a desperate housewife, Dorothy, trapped in a loveless marriage, who falls in love with a “six-foot-seven-inch frog-like creature” escaped from a science lab) as: “So deft and austere in its prose, so drolly casual in its fantasy”. In 1986 it was listed by the British Book Marketing Council as one of the top twenty American novels of the post-World War II period.

Faber’s Chairman, Charles Monteith, described her as ‘a genius—not a word I use lightly’ and published her debut in 1970. Since then she has been praised by Margaret Atwood, Joyce Carol Oates, Ursula K. Le Guin and Daniel Handler (aka Lemony Snicket) who told me that Ingalls is a favourite author, having discovered her by chance whilst at college, picking up Binstead’s Safari (1983) in a bookstore and was ‘electrified by it’.

Ingalls was passionate about Shakespeare, opera and cinema. In a 2018 interview, Ingalls said the Gothic element in her work comes from an ‘early exposure to Hollywood horror films’ such as The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954). She would often see four films a day at the NFT, such as the Soviet silent film The Bear’s Wedding (1925) about a man who turns into a bear, murders his wife and drinks her blood. As Handler put it, “she recognises Beowulf when she sees a cheesy monster movie”. Ingalls said she thought that ‘the so-called monster was always more exciting than the drippy husband or fiancé.’

The story, ‘Friends in the Country’ is an allegory about coercive dynamics between a young couple who take a wrong turn when driving to a dinner party, enter a macabre mansion and try to leave with supine inability. Love can be a war zone: “there are all kinds of prisons in the world. Everywhere”; even domesticity is a death-trap.

Her father, the Harvard Sanskrit professor, remarried after the mother’s death and Rachel never published again. ‘I sensed she wrote for her father, she was obsessed with him,’ her close friend, the painter and novelist Hugh Fleetwood told me. Ingalls’ introduction by her father to the ancient Indian epics no doubt sowed the seeds of her fascination with liminality as in the story, ‘Blessed Art Thou’ where Anselm, a young monk, is seduced by the angel Gabriel. The power of his lovesickness turns him into a woman and he falls pregnant. Ingalls uses myth to examine gender and spirituality: (“Do you think we’re what our bodies are?”) and decades before our current ‘terf’-war.

Her darkness is offset with anarchic humour. ‘In the Act’ riffs on Ovid’s tale of Pygmalion: when a wife discovers her toadish husband has made a female sex doll called Dolly, she enacts a revenge of equal rights, kicking off a carnival of chaos. As Handler opined, “the love affairs in her work have the footprint of fear in them and show you why one stays with someone who just insulted you and how you make up your own narrative like a gauzy curtain in front of who they really are.’”

Upon meeting Ingalls, Kate Wilson (also at Faber) said that she was “astonished that someone so shy and diffident, and almost child-like could have written something of the calibre, oddness and passion of Mrs Caliban“. Fleetwood told me that “Rachel was ‘full of contradictions which is what I loved about her. She was incredibly fey but underneath there was vanadium steel’.” Friends with Jean Rhys, Ingalls was kind and caring, sending the “down-on her-luck Rhys a rug to keep her warm in Devon and a bottle of whisky”, her executor and confidante the publisher Kate Pocock told me.

Writing for her was a ‘compulsion’ she expressed in a letter. Ingalls had other compulsions too, buying “thousands of clothes, tags on, kept in their bags” including a “Versace dress that she never wore.” Did she have lovers? No-one knows for certain; she was, according to Fleetwood, “secretive”. Ingalls certainly never married. She had a German lover as a student but broke off the engagement: “I don’t think she wanted anybody to control her. She lived in her own world and I’m sure she didn’t want children, so why marry?”

Anyone who reads Ingalls’ work knows that she has lived a thousand metaphysical lives. She has loved monsters and men, fallen pregnant and miscarried, been the betrayed and the betrayer, suffered imprisonment in a bitter marriage, lost her mind, found it, thrown herself into the jaws of a lion and been set aglow by the fire of love.

I long for her tales to light up the silver screen.