*You can purchase Young Kim’s acclaimed new memoir, A Year on Earth with Mr. Hell, here.*

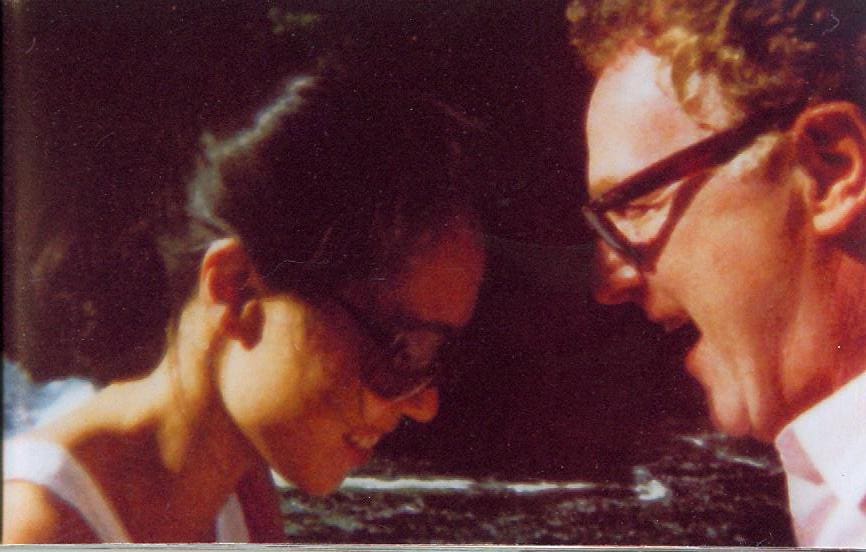

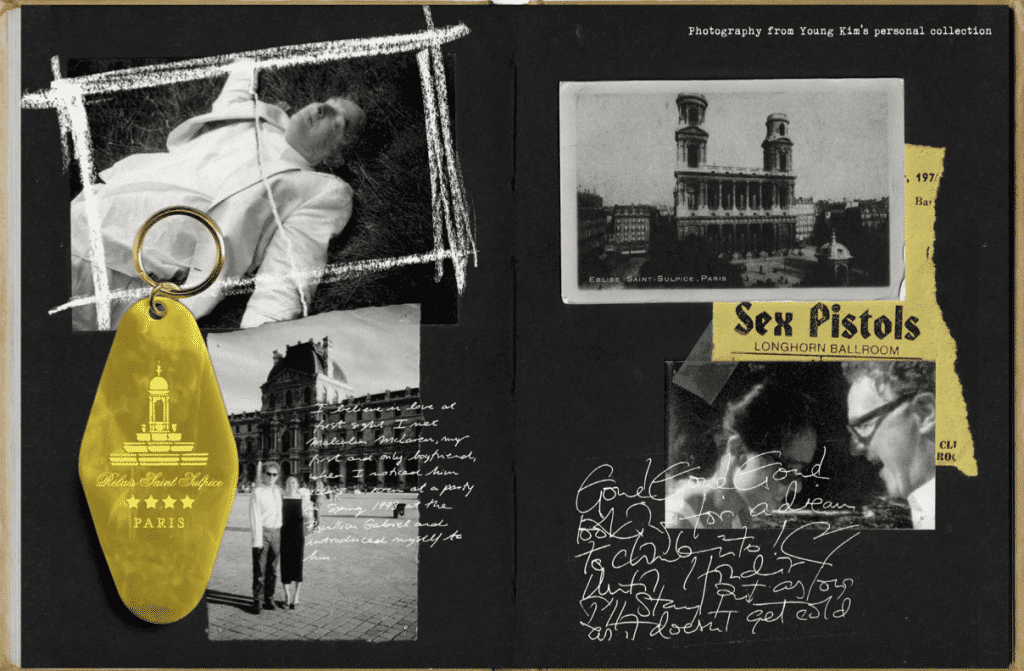

I believe in love at first sight. I met Malcolm McLaren, my first and only boyfriend, when I noticed him across a room at a party at the Pavillon Gabriel in Paris the Spring of 1998. It was, in fact, Vivienne Westwood’s after-show party. I didn’t know much about him but seeing him standing there, talking to his son, I thought he simply looked magical.

Though I’m naturally shy and dread talking to strangers, I didn’t think twice but went right over to him once his son had walked away. “I’ve always wanted to meet you,” I told him. How I came up with this line, I have no idea. It wasn’t true. (The person I’d always wanted to meet was Mikhail Baryshnikov.)

I knew little about his history and was aware mainly about what he was doing at the time from the current press— helping the Polish government make Warsaw hip and managing a Chinese girl band called Jungk. He was really into China. He felt it was the next big thing. So, unlike most people, I didn’t bring up his past. Maybe that was what made him interested in me. I wasn’t an obsessive punk fan like the majority of people who accosted him.

Malcolm did many important things in his life, but he was best known as the godfather of punk, turning what he initially discovered in New York into an audio-visual political and artistic movement, most famously with the Sex Pistols. He sold the clothes he designed with his partner at the time, Vivienne Westwood, in the shops he created at 430 King’s Road: Let It Rock, Too Fast To Live Too Young To Die, Sex, Seditionaries and Worlds End. His shops were Gesamtkunstwerke and brought together his art school education and fashion background. (His mother had had a successful dress factory and his grandfather had been a master tailor on Savile Row.) Each iteration, at the same address, had a specific concept and style that he devised: interior, exterior, graphics, philosophy, clothing and music.

When our conversation wound up, he gave me his card, (from Smythson, he later pointed out to me) which had only his name printed on it. In his beautiful handwriting, he wrote on its back the name of the hotel he was staying at and told me to call him the next morning at 10 and he’d tell me where we would meet for the Yohji Yamamoto show the following evening. The rest, as they say, is history.

At the time, I was studying fashion in Paris and he lived in London so he would regularly take the Eurostar to come visit. Paris was a special place for him. It was always a place of refuge and inspiration. He’d gone there as a student and after the disastrous Sex Pistols hearing, he ran off to Paris to lick his wounds. Paris was where he discovered the Burundi beat which he gave to Adam Ant and Bow Wow Wow and sowed the seeds of his first solo album, Duck Rock. A few years before we met, he even made an album called Paris, featuring Catherine Deneuve and Françoise Hardy. It was also a city where he was known by those who knew, but not by the public at large, unlike in London. There, everyone knew him—from the garbage collectors and construction workers to the cab drivers and shop assistants, all shouting his name…fans rang his doorbell and rifled his garbage. In Paris, he would be left alone.

When he called saying he might come visit, he’d play with me and keep me hanging because he knew I was crazy about him. He loved creating drama and making me beg him to come—to show how much I cared. Of course I knew it was all a bit of a charade and deep down, he cared. I knew he would come if he could. Though it drove me nuts, I loved it all and it made me adore him even more.

“I’m coming!” the voice threatened gaily. “I’m coming on the choo-choo! There’s a train in a couple of hours that will get me to Paris in time to take my baby to dinner. Wouldn’t that be nice?”

“Oh Malcolm! That would be wonderful! How exciting. I can’t wait to see you! What time will you get in?”

“We-elll…” the voice turned coy and dangerously non-committal. “I’m not sure. I have to see. Only if I get my work done. Otherwise, Sarah will be angry.” Sarah was his assistant and the way he talked about her, she was in charge and scary. He made her sound like Nurse Ratched.

“Oh Malcolm, but you have to come! You have to!”

“I’ll see…” he replied with glee, having hooked me. “I can’t promise. I’ll call you later. Byeeee!”

Oh, he was exasperating. I just had to wait patiently, hoping he would get his work done. I knew better than to call him back. One thing I’d learned, and very quickly, was never call a man at work unless you want to be upset. The same person who could be so sweet could be a growling, aggressive monster if you caught him at the wrong moment. There was nothing I could do except occupy myself.

I decided to take a hot bath. It would mean one less thing to worry about later if he did come. I always bathe in the evening—an Asian tradition. The idea is that you relax and go to bed clean. I took the cordless phone with me to the bathroom.

Sure enough, as I was in the bath, the phone rang.

“I’m coming!” he announced in a formal manner.

“Oh, I’m so thrilled Malcolm! What time are you arriving? I’ll come meet you at the Gare du Nord.”

“What’s that sound?” he asked suspiciously.

“It’s the water splashing. I’m in the bath.”

“The bath! What are you doing with the phone in the bath!” he shrieked. “You’ll electrocute yourself! I know someone who died that way! Claude François!”

“Don’t be silly. I’m not going to drop the phone in the water. And a little battery couldn’t electrocute me.”

“Get out!” he screamed.

“Oh, stop it!” I laughed. “What time are you coming?”

“My Eurostar gets in at 7.45. I’ve booked a room at the St. Sulpice.”

“OK. I’ll see you then.”

“Gotta go…. Byeeee!!”

I arrived at the Gare du Nord well ahead of time and waited at the end of the platform, anxiously watching the clock. The train chugged in and a stream of people started to come down the platform. Soon, I saw him: his curly hair waving from the incredible velocity with which he sped along the platform, one hand grasping a smart forest green canvas and brown leather bag—part of a set from Swaine Adenay on Savile Row. I waved to him excitedly, rushing towards him, catching his eye.

“Well, you rascal! You’re here. Are you happy to see me?” he demanded. “Of course, Malcolm! Of course! You know that!” I insisted earnestly, practically jumping up and down with joy. “Well, then give me a kiss!” he ordered. I threw my arms around him and kissed him. “That’s better!” he proclaimed. “Let’s get a taxi now,” he stated in a business-like manner as he spun around and headed off. I scrambled after him. I walk incredibly fast. But Malcolm was faster—the only person I’ve ever met who was. “You wear different shoes from him,” observed a male friend dryly when I mentioned this.

The Relais St. Sulpice and later its sister hotel, the Hotel des Jardins du Luxembourg became our regulars. They’d recently been bought by Swedes and totally refurbished. They were central and charming in a traditional style but there was nothing fuddy-duddy or old lady-ish about them at all. The walls were padded and covered over with floral patterned calicoes—something completely new to me.

Malcolm had had a lot of experience with hotels and he knew a new hotel was a clean hotel. Like its name, this hotel was just off the Place Saint Sulpice in Saint Germain des Prés, on the Left Bank. The Hotel des Jardins du Luxembourg was about a ten-minute walk away on a quiet impasse a stone’s throw from the gardens. We always stayed in one of the two rooms that gave directly onto the street. You didn’t need to go through the hotel itself but unlocked the door from the sidewalk. Malcolm liked hotels that were not like hotels—more like your private apartment so people didn’t know your business.

Though we lived in many different parts of Paris, Saint Germain and the Left Bank was in a way, Malcolm’s spiritual home and became mine. He loved its history— the Sorbonne and the Ecole des Beaux Arts, the student revolts, the Beatniks, the writers, artists and philosophers, the little repertory cinemas, cafés, antique shops, clubs, bars, the Luxembourg Gardens… He’d discovered the hotel because it was just behind the studio where he’d created his Paris album.

From our room, we could hear the bells from the Saint Sulpice church, which he’d recorded for the album. He took me around the corner to visit it, explaining that it had never been completely finished—hence the mismatched towers. A series of architects had worked on it and the last, unhappy with the result, committed suicide shortly after the work finished. He led me inside and showed me the Delacroix frescoes.

In front of the church, in the middle of the square is a grand fountain with lions. On the North side of the square is the fashionable Café de la Mairie, with a large terrace. It was there that Malcolm had watched and waited for Catherine Deneuve to emerge from her apartment nearby so he could recruit her to sing on his Paris album.

Another hotel we stayed at was the Duc de Saint Simon. There was a special Blue Room that Malcolm liked. “Fergie’s stayed here,” he explained to me. That made me laugh, that he would care about such a thing. Though he was a punk, he still got a kick out of these silly things. He was tickled when the hotel staff referred to me as his “fiancée.” His glee was undimmed when I explained that this word had a different meaning in French. It means “girlfriend” and not that you’re engaged to be married. “The hotel must be thrilled to have such a nice young couple like us staying here,” he mused happily to me. I just smiled and nodded. It was charmingly delusional. To the day he died, I never thought of Malcolm as old and there was never anything old about him. Except for his face, his skin was rosy and without a wrinkle. Even his hands and feet looked like they’d been born yesterday. But he was, after all, fifty-two by the time we met and truthfully, not technically “young.”

Malcolm liked to eat breakfast in bed. This was new for me as I had been brought up to never eat anything except properly seated at the dining table. (You never ate lying down nor did you eat while standing up either—“You are not a horse,” my mother would lecture.) Furthermore, I felt embarrassed to be lying brazenly in bed clad only in a slip with a man I obviously wasn’t married to. “Answer the door,” Malcolm ordered. “I can’t!” I squeaked, wondering what to do. “Answer it,” Malcolm repeated. “No!” I refused, throwing the sheets over myself. Giggling, Malcolm opened the door himself, admonishing me, “Get out from under there! Don’t be ridiculous.” But I stayed put until the door closed. He placed the tray on the bed and we tucked in to eat the crusty croissants, drink the warm coffee and fresh orange pressés and fight over the International Herald Tribune. “You know, I can read too!” I’d complain, trying to steal some of the pages as he deliberately ignored me and hogged the paper to tease me. It seemed so wonderfully decadent to me, especially not having to worry about scattering crumbs in the bed.

We loved doing the same things—we were both flâneurs— visiting exhibitions, watching films new and old, going to markets, and checking out shops. I wasn’t used to sitting around in cafés or eating in restaurants as I was still a student. (I even had a roommate, which was why we stayed in hotels.) I’d never had the money to do this, but of course I enjoyed that too.

He explained how the French gardens were strictly geometrically designed and manicured, whereas the English had rambling, seemingly wild gardens. Gardens for eccentrics, made for sitting on and lolling about in, having picnics, unlike French ones where you’d sit in a stately manner in a metal chair painted olive green on the gravel path.

In fact, in Paris, in most cases, you are not allowed to step foot on the lawn. One section in the Luxembourg had a sign that only four-year-old children and younger were permitted. “You could sit there. You’d fit right in,” I suggested to Malcolm. He was such a giant child. As Malcolm liked to lie on the grass, we would have to find a far-flung corner where there was no restriction. He would flop down blissfully, while I sat uncomfortably on a piece of paper I would tear off from my notebook. I would have preferred to sit in a chair on the path, but Malcolm would demand that I stay right next to him. And though reluctant at first—I’m always convinced a bug will crawl up my leg under my skirt— I was happy to indulge him.

“You belong right here, under my arm, just like my Pooghie Bear” he’d insist. When he was a small child, he was inseparable from the arm of a teddy bear that he called his “Pooghie Bear.” “I only had an arm,” he’d explain mournfully when I asked what happened to the rest of the bear.

Over time, I did become his Pooghie Bear. He would barely let me out of his sight and he’d trust me with everything. My love for him was unconditional and he was perfect to me in every way. Even his flaws were charming. I would do anything for him, perhaps begrudgingly at first about certain things, but ultimately happily, as it gave him pleasure. I tried to do everything for him so he would only have to think and be creative. Why should he bother with anything else? He was a great artist and a wonderful, magical person. He loved being taken care of, possibly because he’d been so neglected as a child. He was needy and I need to be needed. As unlikely as it was, we were perfect for each other and Paris eventually became our home.

Somehow, though I was so inexperienced, my instincts were accurate. I had seen something all the way across the room at that party in Paris, just as in the song, “Some Enchanted Evening” from Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific:

Some enchanted evening, when you find your true love,

When you hear her call you across a crowded room,

Then fly to her side and make her your own,

Or all through your life you may dream all alone.

Once you have found her, never let her go.