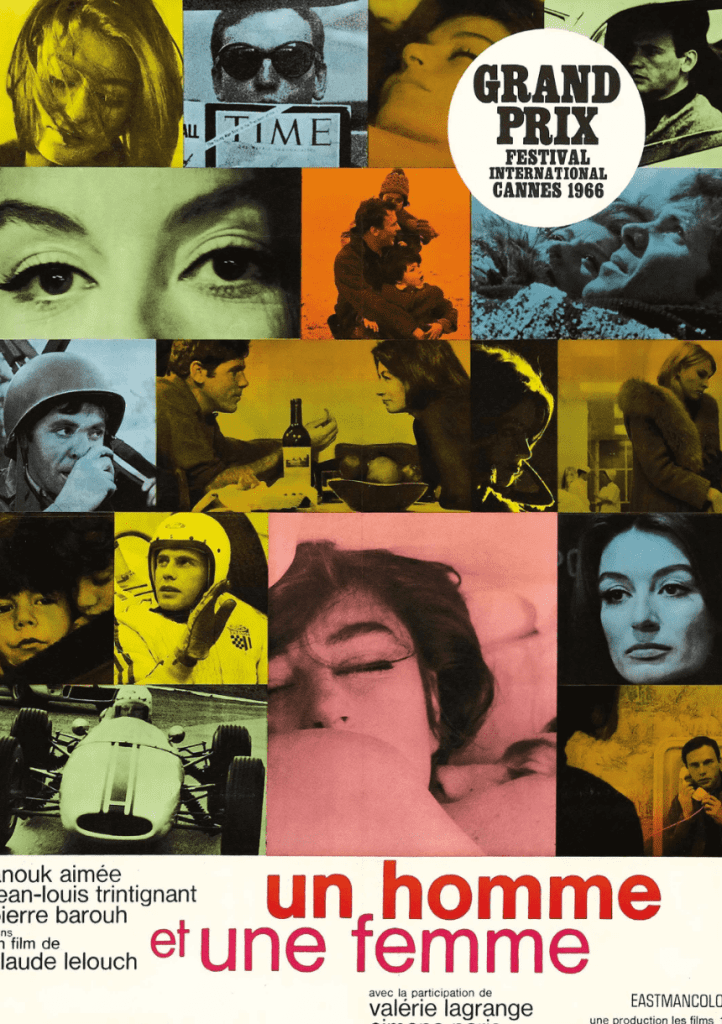

Winner of the Palme d’Or at the 1966 Festival de Cannes, Un Homme et une Femme is one of the definitive romantic movies of our time. It won Academy Awards, Golden Globes and armfuls of awards at international festivals, and yet, with all its impressive prizes, accolades and popular successes, what matters here is what is at the heart: the most beautiful love story between a man and a woman.

That story is a very simple one, as suggested by the title of the film: a young widow and widower meet by chance at their children’s boarding school.

Claude Lelouch established himself as the master of romance with this film. The difference with his peers from the New Wave and other 60s French filmmakers such as Louis Malle or Alain Resnais is that Lelouch films are pure and essentially well-meaning romances.

François Truffaut is another master of the ‘Love’ genre, however in his films, from La Peau Douce to La Femme d’à côté, love always comes with emotionally sad circumstances and “tragedy”—which is the literal translation for “drame” in French. Indeed, the word Drama in English is used for theatre, radio or television and cinema. But in French, Drame is not a film genre.

In the film, Jean-Louis Duroc, the character played by Trintignant, says to Anne Gauthier (Anouk Aimée) that in life, when something is not serious, we say “it’s cinema” and asks her why she thinks we don’t take cinema seriously. I believe that with this film, Claude Lelouch tells us that (his) cinema is about love.

Jean-Louis Duroc

Dans la vie quand une chose n’est pas sérieuse on dit c’est du cinéma. Pourquoi vous pensez qu’on ne prend pas le cinéma au sérieux?

Anne Gauthier

Je ne sais pas, moi. Peut-être parce qu’on y va quand tout va bien?

Jean-Louis Duroc

Alors vous pensez qu’on devrait y aller quand tout va mal?

Anne Gauthier

Pourquoi pas.

Many think of A Man and a Woman [the film’s English-language name] as the ultimate love story. Four years after Truffaut’s Jules et Jim and Godard’s Le Mépris, Claude Lelouch gives us a film with romantic passion, and a positive outcome. Resisting the melodrama of films like The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964) where sensational drama is played out by exaggerated characters, the romance between Jean-Louis Trintignant and Anouk Aimée hardly needs any words. The dialogue is light, the love scenes are passionately tender and the film is full of soft transitions. We are led from one section to the next with lush cinematography effortlessly blending full colour, black-and-white and sepia-toned shots.

Lelouch was a pioneer in mixing different film stocks: black-and-white, colour, 35mm, 16mm and super 8. For years film critics debated the symbolism of the mixed film stocks, but Lelouch eventually acknowledged that the primary reason was that he was running out of money, and black and white stock was cheaper. His original plan involved shooting strictly in black and white, but when an American distributor offered him $40,000 to film in colour, he filmed the outdoor sequences in colour, and the indoor scenes in black and white. If necessity is the mother of invention, then like love, Lelouch’s financial difficulties reflect a movie whose very soul oscillates between the vibrant highs and monochromatic lows of its two lovers.

The film also gives us one of the most memorable musical scores ever written. Francis Lai’s composition immediately appeals to the emotions, particularly in France where the film’s theme song has been a part of almost every family for generations. Lelouch said that the soundtrack was recorded prior to filming, and that he would play the music on the set to inspire the actors.

In France, we used to allow ourselves to create sensual and overtly romantic stories. The musical embodiment will come a few years later with Je t’aime… moi non plus, the famous 1969 duo song by Serge Gainsbourg and Jane Birkin, although first written for and recorded with Brigitte Bardot in 1967; which Gainsbourg would turn into a film of the same title eight years on. Just like Francis Lai’s score, music, love and cinema are never far apart for the French.

Although I was born 22 years after its release, I always felt connected with Un Homme et une Femme, in its simplicity and its charm. Jean-Louis Trintignant and Anouk Aimée had something mature about them, there was nothing forbidden or perilous in their love story. Of course there is Lelouch’s craft and skills at putting together striking images and a strongly evocative musical score, but the beauty of A Man and a Woman comes from the poetry and the universality of what happens when two people fall in love.

Naturally there is the place where it all happens: Deauville, where the romance grows against the cold, windy and wet Normandy winter. The resort is now a romance gateway, and the film A Man and a Woman certainly added to the charm of Deauville, often referred to as the Queen of the Normandy coast, ‘Paris-sur-Mer’ or the ‘Riviera’ of Normandy.

Notable for its long sandy beach, beautiful Belle Epoque hotels, casinos and racecourses, Deauville has been a playground for passions and whims of the rich and famous since the mid-19th century. In 1913 Boy Capel even rented a shop between the casino and the Normandy Hotel for his creative lover Coco Chanel. French romance and American auteurs are inextricably linked here, and Deauville has hosted the annual American Film Festival since its creation in 1975 to promote independent American cinema in France.

If the setting is enough to inspire the flâneur in you, Lelouch’s love for cars, or rather the allure of the Ford Mustang, is the final passion of A Man and a Woman. It’s far from an action movie, but two years before Bullitt, the Ford Mustang has a pivotal role in the film. Jean-Louis Trintignant plays a race-car driver (the actor was an amateur rally driver in real life and both him and the character share the same first name) so there are multiple scenes with people racing and working on cars. After receiving a telegram in which Anne tells him that she loves him, Jean-Louis drives back to Paris after competing in the Monte Carlo Rally in his 1966 Mustang race car. Of course, Jean-Louis and Anne fall in love in one. And it is the same Mustang that Jean-Louis drives to the Paris train station at the end of the movie, so he can meet Anne again after their goodbye in Deauville. After all, when a woman sends a telegram ‘like that’, you go to her no matter what—you race towards love.

In 1986 Lelouch directed a sequel, A Man and a Woman: 20 Years Later, but it wasn’t coherent as a self-homage and the only moments that worked were the flashbacks to the previous film, or when Trintignant and Aimée were allowed to develop any intimacy. What we all wanted is more of the “dabba dabba da, dabba dabba da”. A follow up to both films, The Best Years of a Life, was released in 2019, and that second-sequel filled me with a nostalgic affection. We see Trintignant lost in his thoughts and dreaming of the one woman who meant so much to him. The Best Years of a Life was Trintignant’s final film during his lifetime before his death last year in June.

As Peter Bradshaw commented in his obituary last year, Jean-Louis Trintignant was an actor of charisma, depth and dark emotions. He first started in Roger Vadim’s And God Created Woman in 1956, next to the emerging superstar Brigitte Bardot and went on with a long and distinguished career on stage and screen, until Michael Haneke’s Amour in 2012, another Palme d’Or-winning drama in which he plays opposite Emmanuelle Riva.

Lelouch said of Trintignant that he was the actor who taught him how to direct actors: “We really brought each other a lot. He changed his method of acting while working with me, and I began to truly understand what directing actors was all about, working with him. I think the relationship between a director and actor is the same as in a love story between two people. One cannot direct an actor if you do not love him or her. And he cannot be good if he or she doesn’t love you in return.”

As Lelouch told me in 2019, when I interviewed him for The Best Years of a Life, A Man and a Woman remains a declaration of love: to its actors, to our cinema, and to love itself.