We have to admit: Love and passion are two of the most mysterious, delicious, horrific, wonderful, catastrophic, paradisiacal, elemental, defining experiences of human life.

We engineer perfumes to inspire them, build whole industries to exploit them, corral them with rules and taboos, write about them endlessly, talk about them eternally, analyse them to death…And yet they remain un mystère profond.

I like to think of life in terms of occasional moments of sublimity and connection, and it seems that the highest form of these is love and passion. I tried to dramatise these moments, delicate as they are, in Before Sunrise and Before Sunset, two films I co-created and co-wrote.

As with our movie characters Celine and Jesse—total strangers who meet through serendipity on a train and then spend a magical night talking and walking through Vienna—we can’t force these lucky surprises. And in the event that we stumble across these experiences, we can’t demand they continue forever. We can, however, cherish them when they happen. We can also remember them, maybe even write about them. And this is one thing I learned from Anaïs Nin, a woman who spent her life chronicling her search for love and passion, and recording every detail in her journal.

I discovered Nin when I was twenty. One day after class I found her book Linotte: The Early Diary of Anaïs Nin 1914-1920 in an L.A. bookstore. She had begun writing in a journal when she was only eleven years old, but her descriptions of her life were so beautiful, so rich. They hardly seemed the product of a heart-broken child who was forced to come to America with her mother and brothers after her narcissistic, philandering father abandoned the family back home in Europe.

I could see while thumbing through her book in the aisle of the bookstore that Nin’s girlhood writing was notably Victorian in style. It began in 1914, after all, when the world was still under the influence of the previous mannered era. But as I stood at the cash register to purchase the book, I looked up and saw that Nin had also (much later, I assumed) written a book of erotica titled Delta of Venus. What possibly could have happened between the prim Catholic girlhood and the publication of the erotic stories?

As we know, life changes us. The people we meet change us—sometimes unexpectedly, which is something I tried to get across in my films. Sometimes out of nowhere we meet people who mark us for life, whose kisses never quite leave our lips. So after finding Nin’s childhood book in that bookstore, I embarked on a years-long journey in reading all of her diaries, falling down a rabbit hole from which I never quite emerged.

I learned that 20-year-old Anaïs Nin had married a young man named Hugh Guiler in late winter of 1923. They’d met at a dance back in New York, but when Guiler was slow to pop the question, Nin’s mother sent her daughter to stay with wealthy family members in glamorous, pre-communist Cuba where she could be presented to all the eligible bachelors. Guiler, who was working as a young banker, high-tailed it to Cuba and quickly married Nin. The bride wore black. Nin wrote in her journal:

God help me, for I am entrusting all to love and binding my very soul to the fulfilment of my human mission. And while the knowing ones whisper: “Love passes, Marriage a failure. Man is selfish,” I stand unwaveringly, in expectation, my soul filled by visions which elevate me above myself.

Nin idealised love and marriage, but it gradually became apparent that, while she may have loved Guiler and even viewed him as a substitute for the loving father she never had, there was little passion for her in the union. She agonised about this for some time, not quite understanding what she was longing for—until someone who was her husband’s diametric opposite appeared.

In early 1931 Nin was introduced to Henry Miller, an American would-be novelist who lived by his wits. Nin had been given some of his writing and recorded in her journal, “It was as potent as a bomb. … There is in this piece of writing a primitive, savage quality. By contrast with the writers I have been reading, it seems like a jungle.” Nin hadn’t known until then that it was this jungle she was seeking.

Miller was invited to have lunch with the Nins in their home in France and the “potent bomb” exploded. Soon Miller was writing secret letters to Nin:

I think I have discovered a title for the book. How do you like either of these—“Tropic of Cancer” or “I Sing the Equator.”…This evening at sunset I lay on my couch and watched the clouds sailing by my window. You can see nothing but the clouds when you lie there and clouds are wonderful when they are punctured by cerulean blue…Sunday morning and no letter from Anaïs. Desperate. Lying on top of you is one thing, but getting close to you is another. I feel close to you, one with you, you’re mine whether it is acknowledged or not…God, I want to see you in Louveciennes, see you in that golden light of the window, in your Nile-green dress and your face pale, as frozen pallor as of the night of the concert…Anaïs, I love you so much!

And so began one of the most passionate love affairs of literary history. But still, it was a moment. The relationship, which was conducted just out of reach of Nin’s marriage and other affairs, had a season of six years or so.

I believe the hole left in Nin’s heart by her father’s abandonment propelled her into a decades-long search for romantic fulfilment. This quest was partially fulfilled in her forties when she met a man named Rupert Pole, but in between she crawled a desert, feeling a painful “hunger,” as she put it. I believe her hunger was for connection, for true love and passion, the kind we experience so rarely.

Nin’s diary helped inspire me to view life as an opportunity to create beautiful moments and to catch those moments in my own diary. I travelled alone on different trips to Britain and Europe, riding through the various countries by train, meeting interesting people along the way, and recording the various stories I accumulated in my journal.

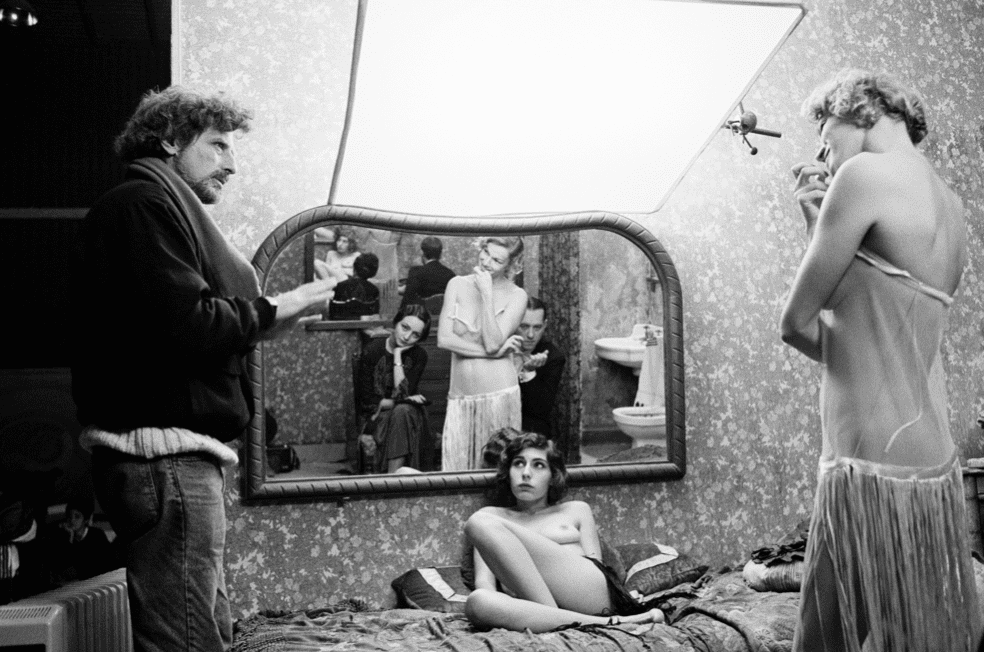

When Richard Linklater asked me to write a screenplay with him, I suggested we use my train travel experiences and this was the genesis of Before Sunrise. In the first scene when Celine and Jesse meet on the train, I had written into the script that the character of Celine, who was based to such a large extent on me, should be reading Anaïs Nin’s diary. That, in a sense, would bring things full-circle. To my disappointment, though, the actress insisted on holding another book in the scene and my nod to Nin was lost. Still, Nin’s influence on me is there, living between the lines.

I believe both Anaïs Nin and I tried to capture within the snow globe of art something of what it is to experience these most fragile and powerful of feelings. Ephemeral though they may be, love and passion truly illuminate our lives.