Sixteen years after humanity had placed a man on the moon, Ireland debated if it could legalise condoms. The dates paint a hard fact: Ireland was a country so press-ganged by the Catholic Church, that sex felt more complicated than rocket science.

It wasn’t until 1995 that Ireland had its next leap forward. Playboy was legalised. Naturally, in a paper-thin margin of 10,000 votes, Ireland was curious enough to allow divorce the following year. There was a lot of masturbating to catch up on. And to the dismay of our dear old pope, a miracle followed each vote: our economy picked up. Then it doubled, tripled, went needle high on every every graph. We even gave it a name that sounds like a Sunday-cartoon superhero: The Celtic Tiger.

It might surprise the world that Ireland’s romance is more complicated than what we let on. We’re passionate about almost everything (the one thing that’s still illegal in Ireland is being boring) and among the 20 words we have for love, the most popular gra means both fondness and pleasure. After a painful start, Ireland might love itself more than it ever has; it might even feel as if it’s on top of the world—but deep down, we’re never far from our troubled history. You couldn’t quite call it melancholy, the word’s too simple.

Our hearts are rebellious things.

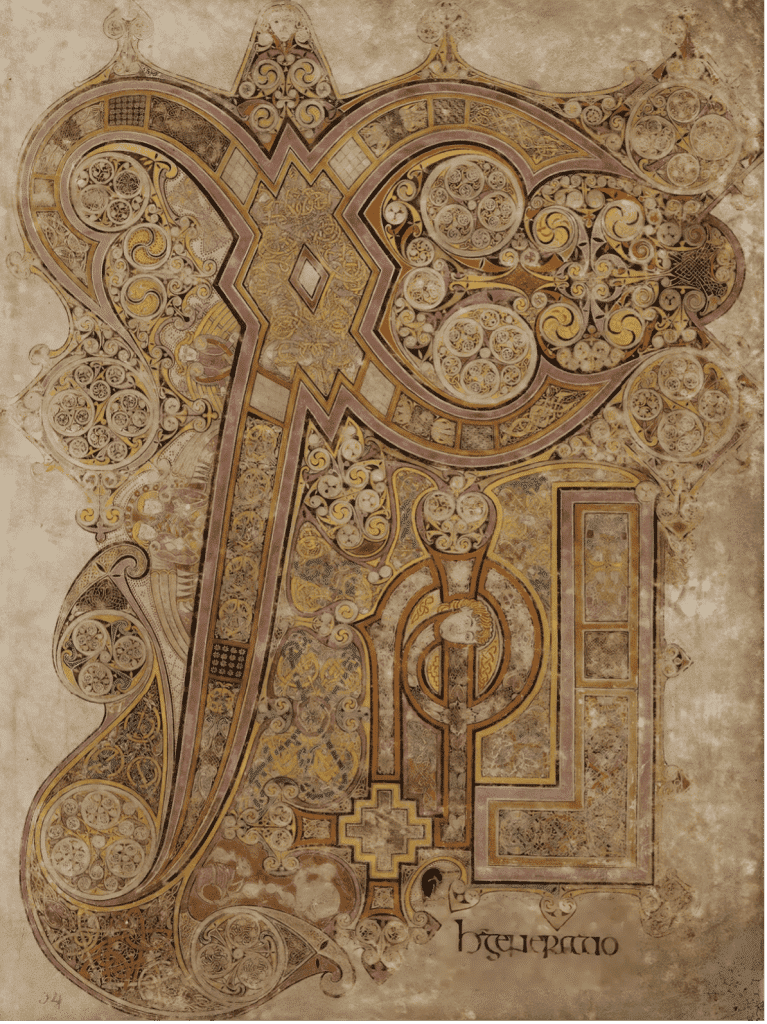

DIRTY BOOKS

To the writer and notable pervert James Joyce, every love story in modern Ireland begins with one man’s broken heart: Charles Stewart Parnell.

Tall and thickly bearded, Parnell was Ireland’s unlikely political voice: a Protestant landlord who used his Parliamentary influence to lobby for Irish independence from Britain to the point he was revered as Ireland’s “uncrowned king”. But Parnell also had one tragic weakness. He was the secret lover of Katherine O’Shea: a woman trapped in a loveless marriage with a husband unwilling to divorce due to his wife’s vast estate.

When Parnell’s affair finally became public knowledge in 1887, Ireland’s Catholic voters couldn’t stomach the cardinal sin. Voted out of power at the cusp of achieving his goal, Parnell died in disgrace the next year. Among his remaining possessions was a white rose that he had kept from his first meeting with O’Shea—her name and the date they met faithfully recorded in the envelope that kept it. With O’Shea laying the faded rose upon her lover’s grave, Ireland’s uncrowned king died two deaths: love, and any dream for a peaceful free state, rotted with his petals.

The Irish mourned the man they turned against as a hero; but now they were voiceless. Shackled to a divisive marriage with Britain, Ireland’s romance was off to a dark start. Assassinations became the mode de resistance; patriotism and religious sympathies quickly dominated cultural taste. By the turn of the century, even literature was under intense scrutiny, and John Synge’s brilliant 1908 play Playboy of the Western World triggered riots across Dublin for the simple crime of satirising the Irish countryside.

Both a sympathetic nationalist and a talented poet, W.B Yeats watched in dismay as his muse Maud Gonne joined the surge, marrying the unstable republican John MacBride. United by a frustrated group of teachers, poets and soldiers, in 1916 Ireland experienced the Easter Rising: a violent uprising for independence in Dublin that saw Gonne’s lover and dozens of other well-heeled Dubliners killed by British firing squads. To Yeats, “a terrible beauty was born”. If Ireland couldn’t get a divorce, it was about to drag itself through hell.

SEX AND CINEMA

Syphilitic from whores, Joyce wrote from across the Shannon waters, in a self-imposed exile in Trieste; enjoying a love nest with a wife he once called his ‘Dirty Little Fuckbird’. His return from Trieste to Dublin was marked by one investment: Ireland’s first ever cinema—Volta. Playing only arthouse Italian and French films, Joyce’s venue closed its doors by the end of WWI to a largely uninterested Irish public.

Joyce may have been the grandfather of Irish cinema, but his venue was mistimed. The Irish were at their wits end; their capital city had been devastated by their first modern revolt, and any further luxuries drained by a global conflict between empires. In 1918, an exhausted Britain relented to Ireland’s request for independence—on an even more tepid divorce: breaking the island into a Protestant British North and a Catholic Republican South that would see guerrilla warfare erupt between its borders for decades.

Somewhat sensing the mood, Joyce’s modernist classic would be published two years after WWI. The writer would boast that if Dublin was “destroyed by bombs” you could rebuild it through his ambitious bookend. A love story set in Dublin over the exact summer day the writer met his wife, the novel’s labyrinthine plot, stream-of-consciousness prose, and forty-page run-on sentence of a wife’s affair led to the novel being banned in Britain and America for indecency (the Irish were too mortified to even sell it). Like any great arthouse film, however, Joyce was a realist at heart: re-inventing literature with a book that was as sexual as it was honest; and all the more stranger for showing it candidly. Like Parnell, his epic was more wild and more lyrical than any polite narrative could allow for; reflecting a country that was impossible to understand in simple terms.

Across the Atlantic, a fresh Irish republic inspired new romance for young Americans. In 1931, travelling across rural Ireland by donkey, a 16-year old Orson Welles would gain his first professional stint in acting— strolling into Dublin’s ornate Gate Theatre and confidently explaining he was a famous American star. The manager was so impressed by the sheer boldness of the teenager’s lie that he gave Welles a leading spot as a stage actor for six months before passing him on to the Abbey Theatre (the very space founded by the dying W.B Yeats to promote Irish nationalism).

Praised as a “smart Jewman” by a confused Irish audience over his opening performance, Orwell would recall his experience years later with his director friend Henry Jaglom. To the great raconteur, while there “wasn’t much fucking” there was an awful lot of repression: one trip to the isolated Aran Islands saw scores of “great marvellous girls” grab him so forcefully it was “as close to male rape as you could imagine”. Eventually, it was the priests—concerned by one too many eager confessions—that asked the young American to keep on travelling.

A quarter Irish but twice as eccentric, the legendary filmmaker John Huston would settle in county Wicklow a generation later in 1952 (eventually giving up his American citizenship to become an Irish citizen in 1961). His son Danny Huston (an actor with the same beautiful baritone voice as his father) gave me a few reasons for the decision. One was the director’s “disappointment” with America’s crusade against socialism in film, seen in initiatives like the House of Un-American Activities Committee. The other was “tax”—artists were, and still are, tax free in Ireland. And Huston, who had already directed Oscar-winners like The Maltese Falcon, The Treasure of Sierra Madre or The African Queen, had ambitious plans for his lifestyle in the emerald isles.

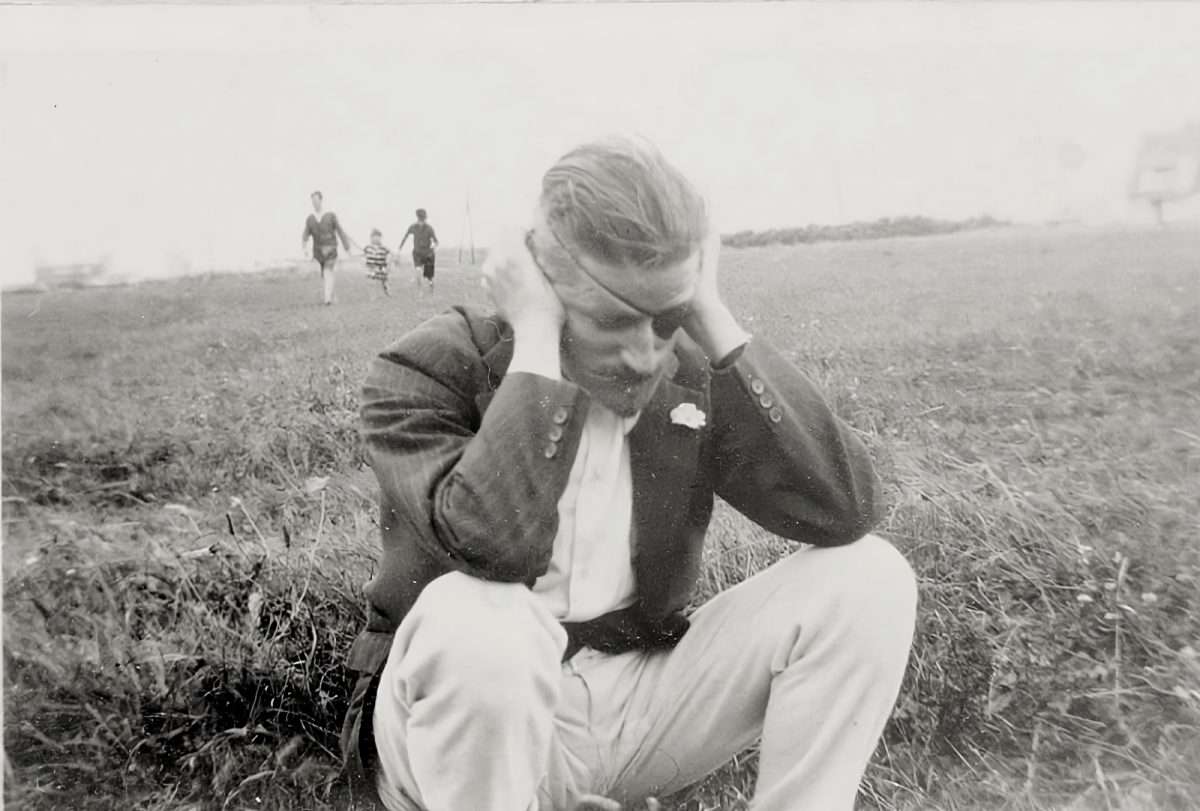

In Peter Viedel’s account of his visits with John Huston, the director quickly imitated a brogue, engrossing the younger writer in a love for fox-hunting trips that drove his wife Enrica Soma so mad in the process that his Irish country manor resembled a “modern version of a Tolstoy novel”. A lifelong womaniser, Huston was able to have convinced his wife he had fallen asleep (fully-clothed) on his secretary’s bed on the ground he’d asked her to untie his shoes while drinking. Always on the hunt, for Viedel, Huston’s personality is that of the perfect Irish contrarian: so in love with the nation’s rural attitudes that you could find “one of Hollywood’s most successful movie directors, sitting in a grimy Irish pub, as pleased as if he had just won an Oscar”.

Between his many travels, Huston would settle in a Galway mansion called St Clarens, raising his daughter Anjelica and Tony Huston inside a building he believed was “the finest country manor in Ireland”. Hosting the likes of Jean Paul Sartre, John Wayne and Humphrey Bogart, his son Danny would call the house more than a little haunted by a ghost and Huston’s children were regaled by an Irish nanny with a fondness for quoting Synge’s lyrical lines from Playboy of the Western World. Never quite faithful, Huston perhaps took Synge’s words to heart; flying away often, but always returning, as his surviving partner Zoe Sallis tells me, to “lick his wounds as the king of his castle.”

So what drove Huston into this home so deeply? To Danny and Zoe, Ireland healed their father. He could paint Galway’s craggy hills that rose above the Atlantic sea that touched his first home, he could roam and hunt (Huston was an ex-cavalry major in an earlier chapter), and he was never far away from his favourite meal of Guinness and oysters. Around and within his walls, people revered him on his own terms; and the Irish liked that he was a man about town (he became the leader of the rural hunting group the Galway Blazers). Most of all, Huston found a mutual love for storytelling. It could be the ghost stories John Huston would whisper to his children, taken from the fey and strange goblins and faeries the locals mythologised, or simply the tall tales that threaded every countryside pub. Put simply, Huston was in love; the gigantic adventurer, with his own troubled heart, had found himself in a fairy tale home.

A TROUBLED REVOLUTION

Published in 1955 J.P Donleavy’s The Ginger Man was a stylistic sequel to Ulysses; a Dublin comedy so outrageous it reads as if Stephen Dedalus’ younger brother smoked ether with Hunter S. Thompson. Of course, Huston was light-years away from the psychotic ginger man Dunleavy created. But the younger American’s novel would mark a shift in Ireland’s culture: while Joyce’s protagonists searched for meaning, Dunleavy’s rich oversexed Irish-American had long given up the chase. It represented a broken Ireland that Joyce’s paralyzed revolutionaries were slowly handing over thirty years on—and a book, unlike Ulysses, that was frightening enough for the state to not just not sell, but ban.

Screened at Cannes and never formally shown in Ireland, Godard’s cinematographer Raoul Coutard and Irish journalist Peter Lennon would create the documentary A Rocky Road to Dublin just over a decade later. Together they put Dunleavy’s comedy to task; painting a picture of a country stubbornly unable to answer the question: “What do you do with your revolution once you’ve got it?”

Despite being filmed in 1967, the documentary delights in feeling dated. Among the profiles are children in the Jesuit schools (the system that educated most of Ireland’s young minds) arguing that: “If Adam and Eve hadn’t committed original sin there would probably be a cure for every disease”. From mod nightclubs which leave the narrator wondering if “perhaps we’ve lost our sense of sin”, to stilted upper-class bars where “Irish woman have long accepted, more or less cheerfully, that they have to patiently lay in wait for the man”—sex was in short supply. The dark comedy of Catholicism looms over it all: a handsome priest puffs a cigarette, joking with gravediggers before a woman recounts a backstreet abortion; and best of all, an elderly film censors describes himself as working “between the devil and the Holy See,” banning movies based on sight alone. In the midst of the madness is an interview with John Huston, puffing a cigar, serene, wearing an Irish flatcap, recounting with his timbered voice:

“Since becoming an Irish citizen I’ve naturally given thought to the best ways I can serve my country. One day I was shooting on this very location when the Taessoch [Ireland’s prime minister] paid us a visit. I took the liberty to point out that a film made by Irishmen in Ireland would be of infinitely greater importance to the country than any foreign film we were making. Ploughing some million dollars into the economy of the country helps, but in the long run that wouldn’t mean half as much as a native film made by Irishmen.”

Just as Ireland had found its own literary identity in its revolutionary years, the nation now had to adapt that to the world stage; it had to translate stories onto the screen, to find something modern. David Leans’ earlier Ryan’s Daughter and its exotic paddywhackery certainly would have rubbed the proud director the wrong way, and John Wayne’s more subtle The Quiet Man might have amused Huston; but Ireland needed a film with the quality of an original epic—the romance of its own history. Not foreign directors cashing in on a country rich in tall tales (something, perhaps, Huston felt conflicted in witnessing.)

Leaving St. Cleran’s after the death of his second wife Enrica Soma and worried by the damp Irish air on his ailing lungs, Huston—keeping his Irish citizenship—also kept thatdream alive. Like the great Irish exile before him, 13 years after his documentary interview, Huston’s final film location would be a story of Ireland written and filmed from abroad, in his new hideout in Valencia, Los Angeles. It was done with the Irish family he raised in St. Clerans: his younger son Tony Huston helming the work as co-director and his daughter Angelica Huston, now beautiful, playing the female lead.

Danny would tell me Huston always “revered the writers” he adapted, and the film was an ambitious recreation of James Joyce’s final short story, The Dead. Based off Joyce’s troubled romance with his wife and her deceased childhood crush, Huston was adamant the movie be as authentic as possible, insisting the entire cast was “real Irish, not just people who claim to be”. In my call, Danny Huston explained his father had rebuked his original idea they film the main plot outside Ireland as a “godawful idea” but Huston health was too low to travel. When the Irish actors eventually arrived in L.A for their “Hollywood experience”, the cast were promptly put in a van, driven in the opposite direction to the Magic Mountain amusement park and told to camp up in a desert motel.

Defiant until the end, however, Huston’s love of Ireland was a success for both relatives: Tony received an Oscar and Angelica was granted an Independent Spirit for The Dead. The director—bound to an oxygen tank throughout the shoot—died with the film’s applause; his last scene a pitch-perfect monologue of Joyce’s closing words on Ireland: linking sex and state together, and lamenting the invisible bond of “the living and the dead” that bind each of us together; like snow falling faintly across the Shannon waters.

CHEAP SPIRITS

Born in a post-war Ireland, the hell-raising buddy of actor Peter O’ Toole and Palme d’or winning actor Richard Harris was an even more outspoken Irish celebrity in film; a man who once venerated the IRA and described Guinness as “health food”. Self-described as “the most promiscuous man in the world”, Richard Harris moved from humble roots in Limerick (with a father who often forgot his name), escaping the confines of an Abbot education, to eking out a meagre existence as a rat-catcher in London and part-time actor. Once terrified by his modest Catholic roots, at the peak of his fame, Harris had overseen a lovelife that included an Empress of Iran, Prince Margaret and Ava Gardner.

It’s no accident that when John Huston made his ambitious biblical film The Bible, Huston played God, and Richard Harris played Cain. Huston was eccentric; but Harris was borderline mad. He was also the literal face of the Ginger Man’s lost generation— a young genius actor who charted the best and worst of that new wave of Irish romance.

Before playing IRA volunteer in The Terrible Beauty (the line Yeats first coined), it was his breakout role in the West-end adaptation of Dunleavy’s The Ginger Man that showed his darker colours. Opting for the Stanislavsky method to get himself ready for the lead role, he devolved into manic binge drinking, merging into the nihilistic wife-beating lead of the novel and striking his just-married wife during black-out sessions while he got into character. Harris was, tragically, pitch perfect for the role, and his performance was lauded; but after three nights into his Dublin run, the production was cancelled due to outrage, and threats of violence, by the Catholic Church.

Moving into film, between his heavy drinking, Harris slowly became immersed in the homegrown cinema Huston hoped Ireland might one day create. In perhaps his greatest performance in one of Ireland’s modern masterpieces, in 1990 the Irish director Jim Sheridan would direct The Field, casting Harris as the farmer Bull McCabe. With the benefit of thirty years, the character wasn’t so much the polar opposite of The Ginger Man role Harris had played before, but a cracked mirror. A hard-faced countrysider not far removed from Joyce’s era, he plays a tragic bully who lyrically walks into a pub and describes foreigners and the rich American investors as the “outsiders who took the corn from our mouths when the potatoes went rotten in the ditches”. It’s a similar colonial premise you’ll see played out as nihilistic comedy in McDonagh’s Banshees of Inisherin (a movie that re-treads Ireland’s traumatic past into nonsense poetry and pastiche) but one that exemplifies the tiredness of Ireland’s pastoral obsession: how, like Joyce wrote, Ireland’s rural, backwards way of looking at itself was robbing it of its own future.

Harris went even further by the time his own curtains closed. With a love between his ex-wives and their children that was like a “fucking fortress” in his own words, Harris died peacefully in a hospital bed at the age of 72 in 2002. His teetotal ex-wife Elizabeth—who had long forgiven him for a string of drunken beatings over The Ginger Man—toasted to his memory with their family. A long way from Parnell, but perhaps no less touching, Harris’ final kiss was from the woman he once beat—sipping on a Guinness and wetting the actor’s dead lips with dark stout.

GRA IN MODERN IRELAND

A close friend of Peter O’Toole and a one-time acquaintance of Richard Harris, the actor Sir Johnny Standing was kinder on Harris when we spoke. During our talk Johnny (who had a penchant for calling me “Darling” and complaining about “this wank of a coronation”) described Harris as a “nice bloke”; colouring his view with the fact their sole meeting was a drunken Harris encouraging him to fist fight a designer they’d met at a party. Standing explained to me that Harris was “totally in awe” of the slightly older Peter O’Toole; the two actors would often work together, and even popped out for a pint mid-play only to miss their set. It wasn’t an odd occurrence either. Michael Caine recalled one famous night with O’Toole that became two days in a blink; and our own editor’s father Peter Finch would buy a Dublin pub with O’Toole after being informed it was closed (the landlord kindly tore up the ruinously expensive cheque after they stumbled their way back in the morning). As Johnny speaks around some of these tall tales—one I’ve promised never to repeat but ends in a nunnery—it’s hard, somehow, not to be swept up by the same passion that makes Joyce, Donleavy, Huston, and their band of artists and pubmen so attractive; each of these Irish artists were outsiders to a degree, rebels in another place; finding solace in the power of their stories.

Today, the Irish haven’t changed their interests so much as their style.

With a record 14 Oscar-nominations this year for Ireland, Ireland’s once small homegrown movie industry is now rapidly expanding; with plans to move well beyond three major studios thanks to government funding. The Irish, however, are staying humble: when Paul Mescal was asked what he’d do with his Oscar nomination for playing the most depressing male lead of the decade, his response was classic: ‘drink’. In a country where whiskey translates to ‘water of life’, there’s a fondness for figures like Parnell et al who make us smile at our darker side. Novel adaptations like Sally Rooney’s Normal People, or new voices like Lisa McGee, Martin McDonagh, or Kevin Barry, are the beginning of our new emerald wave; a wave that’s learnt, like Joyce and Donleavy, to enjoy the darkness ever so slightly—only this time, we’re determined not to let it hold us back.

Even though we’ve joined the rest of the world in pretending there’s some clear pattern to the human heart, we haven’t quite left our old one behind either. If you go to Galway, to the very end of Ireland, that famine-ridden and beautiful countryside Huston settled into, you’ll find the same folk stories they regaled him with. You’ll find water wizards, arson, and pot-shed shrines. Tall tales. A bit more sex. Houses that look like smashed seashells, ruins from the hungry 1800s. A quick glance at our tourism board will show you how Ireland is in love with that Ireland too, and it’s a love like a winding stair. We move forward—but our hearts notice the circle. Deep in our national psyches is a winding connection to a pained history. Only there’s joy in it. Because all the trials, rebellions and successes we’ve had since the moment we we got here—well, they’re all part of one fond, lyrical sound:

gra.