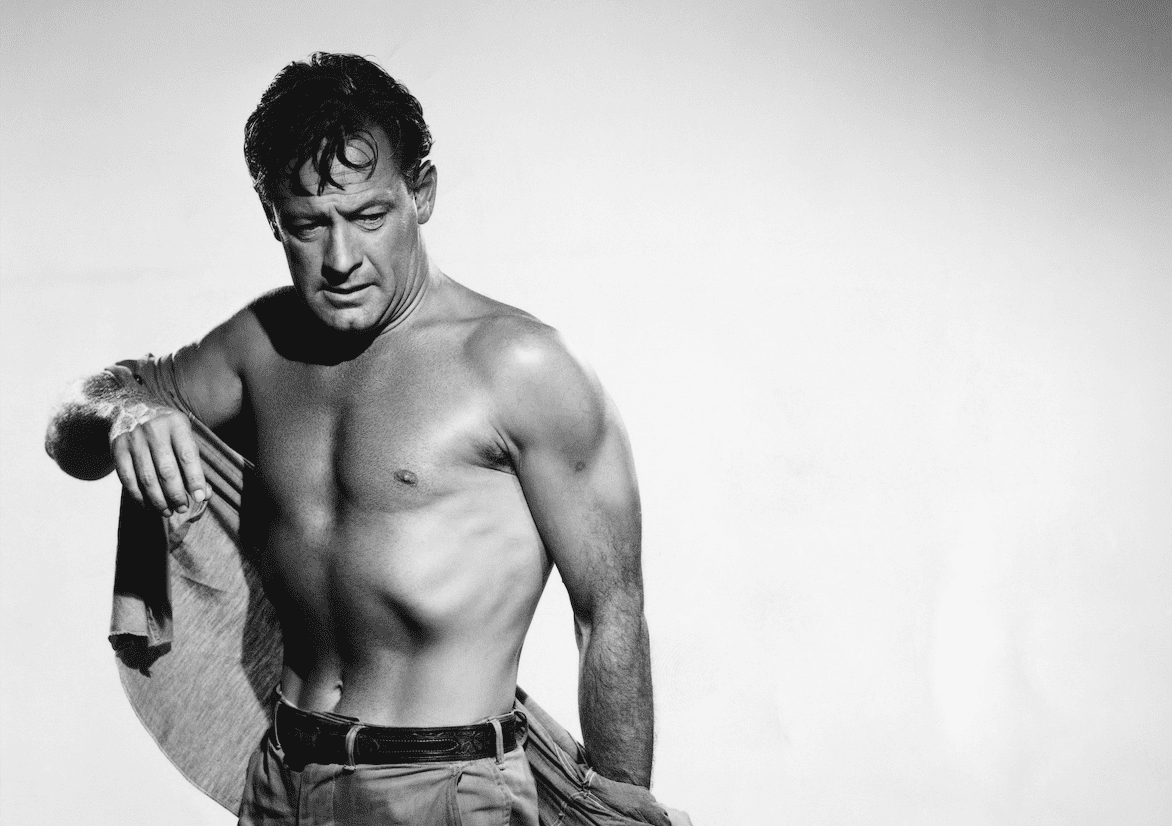

Over the 1950s William Holden’s legend was forged as an actor who had the “missing gene” for turning films into hits. By the age of thirty-nine, he was so popular with the public and critics that he was able to negotiate 10% of the royalties for starring in The Bridge over the River Kwai (1957). The film’s global success led to Holden becoming one of Hollywood’s first-multi millionaires. Notoriously shy, it was an upturn that coincided with the star drifting away from film to explore the remote edges of the world; a move the writer-director Billy Wilder (who landed him his first Academy Award in 1954) described as: “virtually abandoning his profession.” Taking a step back, Holden founded the Mount Kenya Game Ranch in 1959: a conservation park he created to hunt the very wildlife he would, in his autumn years, dedicate himself to protecting.

To understand what drove these remarkable shifts, I tracked down Stephanie Powers—a famous actress in her own right, and the surviving soulmate of Holden. Jaded by journalists who’d romanticised Holden’s privacy and public battles with alcoholism, Powers was “happy to set the record straight” but quickly cautioned against “superimposing” a modern outlook on the actor’s journey:

“Remember that a few years before social media, before smartphones, even just twelve years ago, life and the way people behaved was very different…Not everyone told all the most intimate details of their daily life for them to read. In that light, it might be difficult for you to relate…but then indeed [Bill’s] times were so very different.”

Different they were. In one of Holden’s rarely intimate interviews, in an hour-long section with the popular TV programme Person to Person in 1955 (the same year he’d be voted film’s most profitable star) Holden speaks with marvel on a world slowly connecting together. In black and white, his portrait seems modern. Sloped between his wife and children in his California home he waxes: “through the medium of motion pictures you can actually go to the jungle…I just feel that I’m terribly curious about the world and the people in it.”

Admitting that he’s been privileged enough to travel thanks to his far-reaching movies, Holden seemed to desire more, and soon entered the foothills of Northern Kenya to hunt game. Accompanied by the Swiss banker Carl Hirschman and Irish oil tycoon Ray Ryan (who was eventually assassinated by a stick of dynamite in ‘77), they safaried in the peak of the Mau Mau rebellion in 1956—a time when locals were constantly armed and the untouched planes were open ranges. It was an experience Holden seemed to find pleasurable: “Every day in Africa,” Bill would boast to his friend and actor Bob Preston years later, “might be your last.” Drinking in the Mugwundu hotel and fuelled by cocktails, a bored writer and a porch side view of the savannahs, the trio eventually decided to buy the struggling colonial property. The lodge took a new name, christened after the speckled peak above them—the Mount Kenya Safari Club.

A spontaneous purchase, the white-walled veranda functioned as a base to explore Kenya and to organise safaris for friends and guests. Although moved by natural beauty, Holden is frank that his purpose over these trips was to hunt: it would take seven years of “[coming] back…sometimes two to three times” before he’d admit to a change of heart. In our talk, Powers would speak of the 1950s as a period when the “word conservation was not in anyone’s vocabulary” and “subjects such as extinction, or pollution of the oceans was only recognised by a small group of scientists…[who] were laughed at for their doomsday philosophies.” Despite Ray Ryan’s efforts to glamorise the lodge and invite every celebrity under the sun (including Winston Churchill and Humphrey Bogart) the hotel ran at under a quarter occupancy for its first three years. The reasons that allegedly attracted Holden to Kenya were, in all likelihood, the same that repelled that first wave of jetsetters: Africa appeared unknown, wild and dangerous.

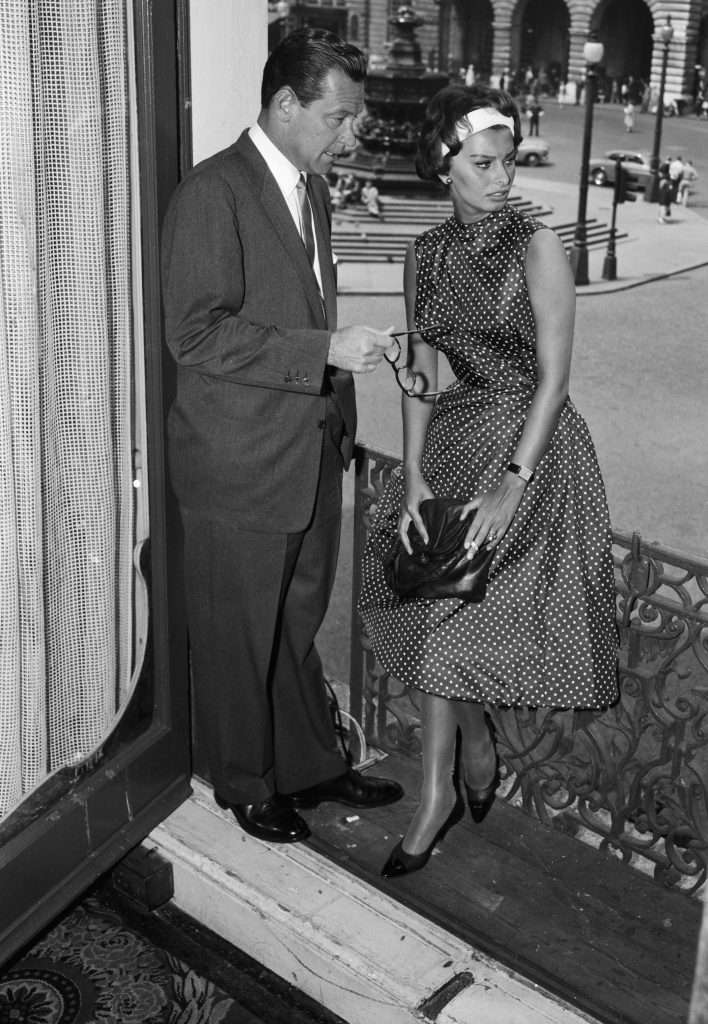

In 1962, with the Mau Mau rebellion pacified, Kenya’s moment seemed ripe. Funding the hotel and local wildlife educational facilities with the profits from films like The World of Suzie Wong (1962), Holden persuaded producer Samuel Engel to cast him as the lead in Lion—on the condition the director shoot the film on the grounds of the Mount Kenya Safari Club. With $100,000 of equipment flown into the remote lodge, Hollywood and the Savannah existed in an uneasy truce. First Holden seduced the Italian co-star and actress Capucine, drawing the Italian model into an on-set affair; according to Powers, Holden was estranged from his wife and sought the blessing of his former agent and film producer Charles K. Feldman, who had a cooling relationship with Capucine at the time. Then, in the middle of shooting, movie prop pythons stored inside the upstairs bathtub would turn on the bath’s water, wriggling out among the terrified guests. Worst of all, ignoring the golden rule on filming with wild animals, Holden’s trainer had his own narrow escape: under the illusion the movie’s lion Zamba had just escaped from his cage, the trainer confused a passing wild lion with the film’s docile animal.

Despite the dramatics, Lion helped position the club as a travel destination when the world was slowly opening up to global travel, although the film was neither a critical nor commercial success. As Holden struggled to make a comeback in film, gossip and fact would mix together cruelly over the 60s—leaving an image of an actor so rapidly aged by the end of the decade it was rumoured he was dying of lung cancer. Having fallen into a brief affair with Audrey Hepburn while filming together in Wilder’s Sabrina (1954), Holden would once more star next to the now-married Hepburn in Paris When It Sizzles (1964). Another disappointing box office performance, Holden allegedly climbed a tree to re-spark his romance with Hepburn (a woman he had once compared to an antelope on a safari) only to fall and injure himself on a car roof. Months later, the actor starred beside Capucine in The 7th Dawn, and their relationship ended shortly after. Their romantic failure was a product, in Bob Thomas’ biography of Holden, of the actor’s “painful” bouts of alcoholism. Although Holden respected Capucine enough to leave her $50,000 in his will, he’s characterized during this time as slowly falling out of love with movies, remarking in a later interview that acting for film was enjoyable “one out of ten times”. By 1966, events seemed to have ended in tragedy: Holden was charged with manslaughter after a traffic accident off the coast of Pisa, having collided with a local driver at enough speed to push the smaller vehicle into oncoming traffic—killing the driver almost instantly.

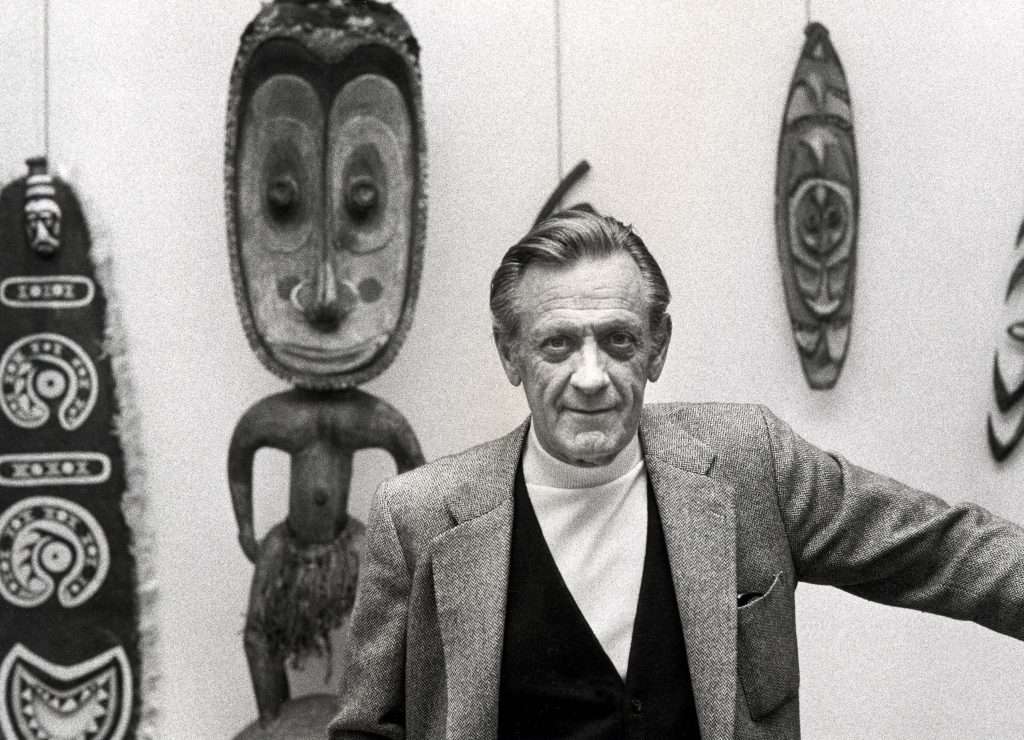

Always on the move, even switching homes after the accident to a Palm Springs penthouse close to the desert that reminded him of the “velvet” air of Kenya, Holden’s wanderlust would reach a point common in all great journeys, a tilt best described by the French travel writer Nicolas Bouvier: “You think you are making a trip but soon it is making you—or unmaking you.” Observing the dwindling wildlife in his regular Kenyan safaris, in 1967, on a trip with the ironically named TV personality Don Hunt, Holden changed the direction of his journey—and Kenya’s—for good: purchasing the hotel’s surrounding 1,216 acres and transforming it into the Mount Kenya Game Ranch; the very first conservation park of its kind in all of East Africa.

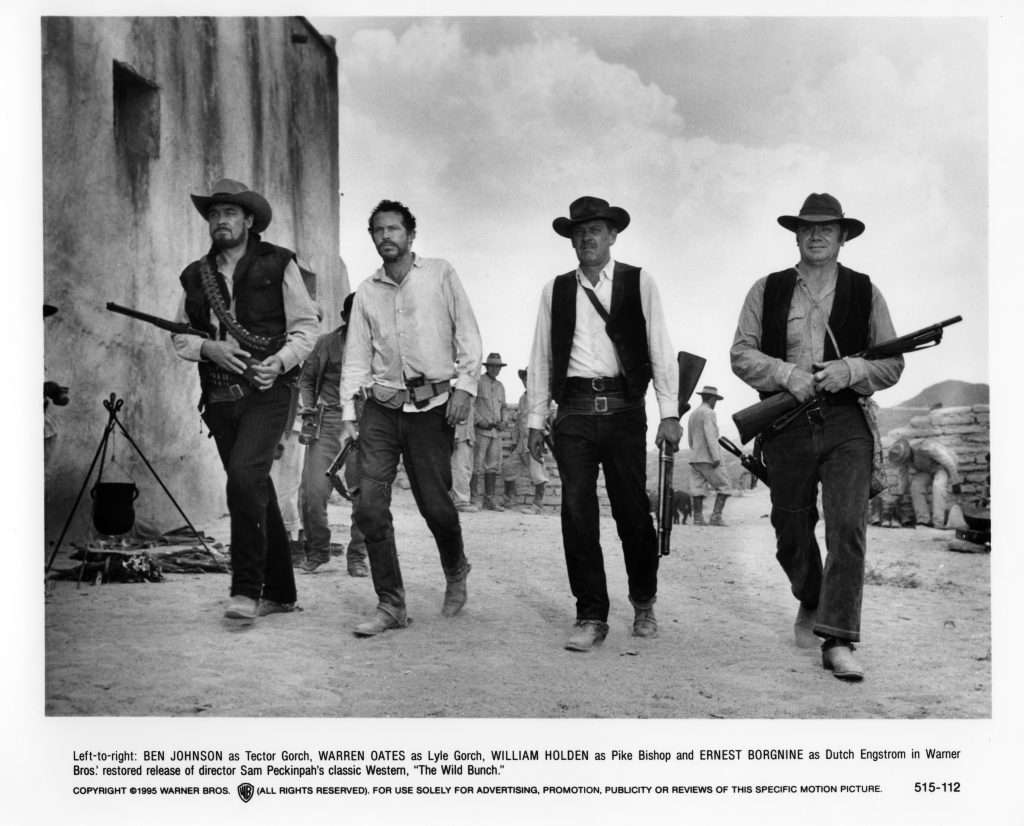

Described by Powers as “engaging with activities which were way out of the ordinary for American movie stars of the time”, despite the heavy investment, Holden’s sudden dedication to animals would not be lauded or even much understood outside of Africa—the public was more interested in seeing the once faded star shoot bandidos in Peckinpah’s bloodsoaked western The Wild Bunch (1969). Before appearing suited and confident on an appearance in The Dick Cavett Show that year, Holden was introduced as “one of America’s most foremost gamekeepers,” and he joked, “I was going into Italy and I wrote conservationist [on my passport] and the fellow looked at me and took the pencil and crossed it out and wrote actor…I guess I have to consider that a compliment because he could’ve written ham.” Asked by Cavett on the difference between a hunter and a conservationist, Holden coolly continued:

“Certain animals have to be cropped in order to keep living…but when a hunter goes out and shoots a trophy animal…what he does is he’s destroying that bull that has already survived a period of years and proven himself to a be a little better…sixty years ago in Kenya it was not uncommon to shoot an elephant and get over a hundred pounds of ivory, and now it’s very rare to find an elephant that has over sixty pounds of tusk.”

Over the 70s Holden’s passion for Africa would develop into a dedicated project to undo the damage he’d witnessed. In ‘72, the glitzy hotel was sold off to the Saudi Billionaire Khashoggi, allowing Holden to focus on healing the landscape he’d purchased. Migratory routes that intersected with humans—known as “conflict zones”—were sealed off or re-routed. Educational centres were constructed to turn away Kenya’s youth from poaching. Over the years, and with the help of the President of Kenya, thirty-seven species of breeding herds—including rhinoceros and bongo—were reintroduced into his range and donated to new animal sanctuaries that were blossoming around the globe. Working also as a Park Commissioner in L.A and planting a miniature African ecosystem in the Coachella Valley, in ‘74, two years after their first meeting, Holden would have a chance encounter with Stefanie Powers at a New York bookstore, seeing the future Hart to Hart star reading a travel guide on Kenya. Always eager to share his passion for Africa with people he respected, Holden invited her to see his conservation ranch: beginning an eight-year romance that led to new highs for the actor.

A generation apart from the likes of Capucine and Hepburn, Powers was able to encourage Holden to attend Alcoholics Anonymous. Sober, the couple travelled the world, building businesses to support the indigenous communities and artisans they visited; people Holden had long idealized as “the last frame of reference for the simple word: mankind.” The period would mark a fresh renaissance for the actor; seeing an Oscar nomination for his role as the tired television president in Network (1976)—a prize narrowly pinched by our own editor’s father and Holden’s co-star Peter Finch, alongside the viciously satirical S.O.B (1980). So often using the camera to laugh at fame, in a media tour for the film, Holden’s focus remained resolute on funding his work in Kenya; relaying, with typical good humour on the John Carson talkshow, the pressing need for conservationism: offering the host “great interviews with gorillas” alongside the heartfelt advice that “people should go [to Kenya] while they can because it may not last.”

In my talk with Powers, she says that Holden never “capitalized”, as he liked to put it, on “his endeavours with wildlife conservation in Kenya”; a landscape he had once described in a travel guide as “magic”. Yet his final moments are marked by a sense of urgency and pride. Famously able to avoid fans in his lodge by smiling and walking at pace, in 1980, Holden would open up the Mount Kenya Game Ranch to the media: inviting a television crew to visit the remote park that was previously off-limits to cameras. On-screen, the actor appears tanned from his travels with Powers, relaxed, years younger, praising the lodge’s impact until he remarks: “for twenty-two to twenty-three years I really haven’t done much to publicise what we’ve been doing…going out and capturing rhino, or elephant or giraffe…there’s going to be a day when I don’t feel like doing it anymore.’’ Tragically, Holden was right.

Falling back into drinking, the star would slip on an antique rug in his Santa Monica apartment months later, cracking his head on a nightstand and bleeding to death quietly in his sleep. Despite requesting a cheap cremation and no eulogy, for a man who had hung himself from a fifth-floor balcony for minutes to prove he could handle his own stunts and was still strong enough to help wrestle a knife from a Chinese assassin on a trip with Powers five years earlier, it was—in Billy Wilders’ forbidden eulogy—a “lousy death”. To the director who first realized Holden’s genius for acting, the world had lost another rare piece of history; a man so authentic, he was unaware that he himself was “an endangered species: the beautiful American.” Over the years, writers and journalists have made their own romances for a man who died at only 63 years old, wondering if Holden was too private, perhaps, or too ashamed, to call attention to his injuries: all I can tell you is that there are no answers to a private man’s mysteries and that writers, given gaps, love stories.

Life, of course, is more enduring than what we invent. Mourning Holden’s sudden death, Powers transformed the Mount Kenya ranch into a global wildlife charity: naming it The William Holden Wildlife Foundation in his memory. Preserving nature and educating over 11,000 Kenyans each year on how to care for the landscape they loved, the slopes of North Kenya remain in good health. But at the close of our conversation, Power says something curious to me: that Holden “was not an activist in today’s language”. In my eyes, Holden is a pioneer, and Powers is far closer to the modern term: working for free and tirelessly publicising the charity she’d once called “the child [they] never had.” On the foundation’s website, a curious reader can still find the last printed message Holden ever wrote, words which criticise the concrete jungle humans are so often born into and words that describe wildlife as “the echo of our beginnings”. Still inspiring people’s lives today, an echo, to me, is a fitting word for what Holden discovered—and what he left behind.

It’s a truth that might be hard to hear, but one that’s travelled far.