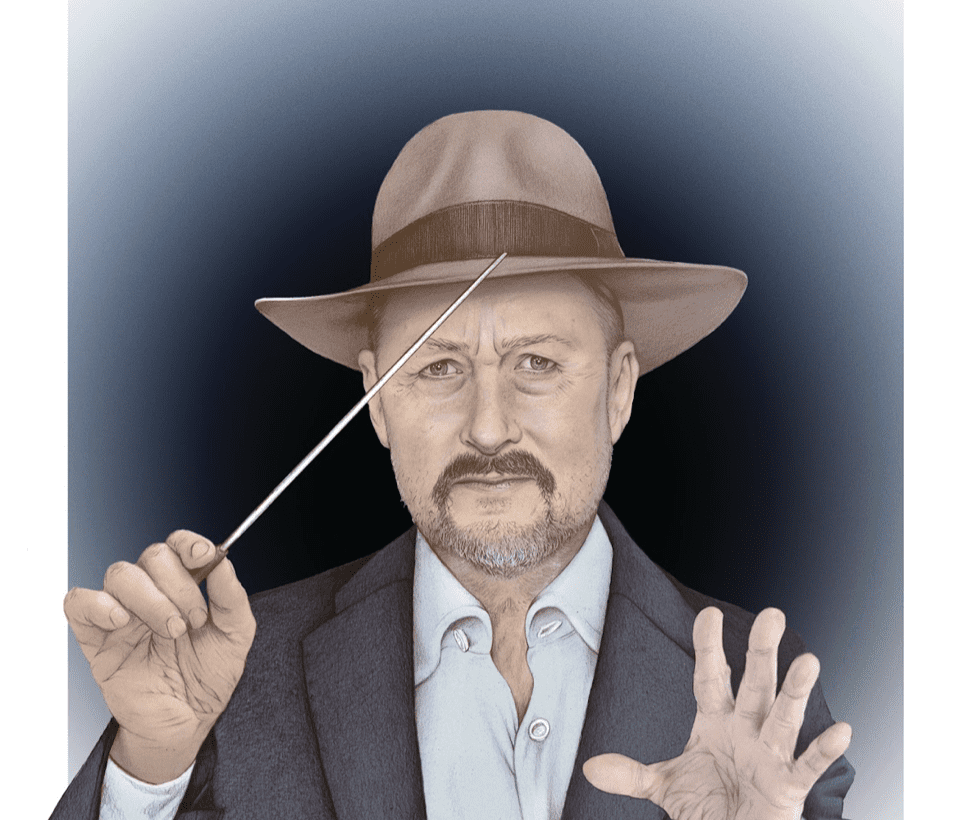

As I walk through the fifth floor of London’s Soho Hotel and enter a room that seems to have been stripped down to its barest bones, Todd Field is already standing, hand outstretched and wearing a friendly smile. Though it’s been around a decade and a half since he’s experienced the slog of a press cycle, the fifty-eight-year-old director looks the least bit worn. In fact, the reality is quite the opposite. Field seems supremely confident in his own skin: the wisdom amassed over his fifteen years away from the spotlight radiating through every gesture and word exchanged.

After a series of stop-and-starts in Hollywood that would see him retreat from feature-filmmaking into the uncharted territory of commercial advertising, Field is back with Tár. Though he reminds me that the story of maestro composer Lydia Tár’s colossal fall from grace could have taken place at any point during humanity’s long, well-documented history of abusing power, it’s hard to ignore the clear parallels to a climate of online cancel culture, identity politics and accountability that has emerged over the last decade. The film feels like Field is taking a stand, not picking a side. He’s not the judge, jury or executioner, but more an observer of greys in a world that has become overwhelmingly concerned with the black and white.

*Spoilers for TÁR below*

It’s been a little while since you’ve had to debut a film in front of an audience like this. How were you feeling before the premiere at Venice this year?

I told Serena Rathbun, my wife, that we needed to go there early so we can have a feeling of this place before the circus arrives. Maybe one of the smartest decisions I’ve ever made [laughs]. Because we watched it get built. It was a beautiful thing to watch the show go up, to watch the carpets arrive. It gave me a sense of the artifice, which was really important, because I was horrified that this film was going to go out into the world. I was terrified. My heart was broken. The only thing that I have that’s analogous would be when our youngest son went to school for the first time—I remember when we dropped him off and he was taken into the classroom. She and I walked out and we pressed our faces against the classroom glass and we watched him, and we wept. That’s how you feel when you work on something seven days a week for years. It’s a hard separation. You’ve been alone with something—with a group of other people—but you’ve been alone with it, for a long time. And you feel protective of it. You’ve spent as much time with it as if you’ve birthed it, and you don’t want anyone to be cruel to it, or mean to it, or dismiss it. That’s how I felt, not to get too confessional. [laughs]

Do you think that was a different kind of terror than the type you might have felt when your other feature films first screened? Did that fifteen year absence from cinema play into that feeling?

I mean, over the last fifteen years I’ve been directing constantly, I do commercial advertising—technically, I feel much stronger as a director than I ever felt with those previous films. I felt very comfortable running a set. It feels like home. But in terms of the anxiety, that goes all the way back to the first film I had at Sundance. I had two short films at Sundance before In The Bedroom, and both times I ended up in the emergency room because I felt like someone had taken a knife and stabbed it through my chest. It was very hard for me to let go. It’s still really hard.

I wonder what lessons you took from your time advertising to this return to feature filmmaking.

Advertising is the skunk works for all new motion picture technology—you’re getting technology and you’re beta testing it long before anyone in the feature film world ever has it. You’re the absolute beginning of something that might be very handy for others. When I started working with commercial advertising, I started to work and learn from different people, and you have to figure out a process of working together very quickly because of the tempo that advertising is executed, your feelings about the process change drastically over that period of time. That was incredibly important, especially in the case of Tár, because other than my first AD slash co-producer Sebastian Fahr-Brix, who I worked with twelve years before in advertising and is Berlin-based, I didn’t know anyone else. I was the only American. Had I not gone into situations where I had to drop in to Australia or India or wherever on short notice to do advertising, that would have been very daunting for me.

There were a lot of scripts that you had written and a lot of projects that you were attached to that for whatever reasons didn’t come into fruition. Did you ever believe that you might not direct a feature film again?

Absolutely. I was going to keep trying, but I certainly had to make peace with that as an absolute possibility, based on a decade and a half of giving your heart to every project and having it go nowhere and having to dust yourself off and keep going. At a certain point where you’ve had fifteen years of ‘no’, that’s a big chunk of your life that is ‘no’. It’s a bigger part of your life than ‘yes’. And so you had better make friends with ‘no’. You had better be able to live in the same room with ‘no’. Or you’re gonna jump out the window of that room.

I know you mentioned that the idea for Lydia as a character came to you about a decade ago, which is interesting to me because it feels very much like the story itself is contextualised by the domino effect of the #MeToo movement over the last handful of years…

Scandal is as old as Nathaniel Hawthorne. The tools of dramatising that scandal are certainly manifested in the present day, but the tools don’t really interest me very much. I had a decision to make: making this a period setting or the present day that surrounds us. I don’t really have a point of view on those tools, but certain things need to happen with the character, so they were handy.

I suppose the abuse of power is both extremely current and also a narrative that is as old as the most famous works of storytelling. Thinking of the very first scene where you see Lydia asleep on a private plane and an unknown is filming her… it feels almost Shakespearean—the modern version of a king being conspired against by his own subjects.

That’s so good! You’re the first person to say that and I’m going to steal it from you. It’s so true. Absolutely. This kind of narrative with a character’s downfall. It’s a timeless story, and it only feels of the moment because it takes place now.

What was the thinking behind placing that scene at the very beginning of the movie? To show Lydia in such a vulnerable position when, for the next hour and a half, at least, we’re seeing her as this über powerful figure.

You’re trying to set up a vernacular that you then follow or you break out from. As you point out, to use the Elizabethan lens…someone’s watching her. Who is it? What does it mean, what are they writing? Do they care about her or do they have contempt for her? It’s asking you to ask a lot of questions, knowing that there’s an expectation that you will get answers to those questions, or that you will seek them out. Yes, she’s vulnerable, as if she was a child asleep in the woods and there are wolves surrounding her. That’s how we meet her, inside that vulnerability. The second time we meet her is when she’s standing offstage getting ready to go onstage, and she’s also vulnerable, for different reasons. These are passively observed, private moments. And then you meet this person that everybody thinks is this person—they’re full of regalia, wearing a very particular mask and dancing that mask for an audience, and looking like they’re the most powerful person in the world. We’ve just seen, twice now, that that can’t possibly be true.

You make it very clear in the movie that there are others who have been complicit in Lydia’s abuse of power, that were using her as much as she was using them. Do you think in the current sphere we’re lacking a nuanced exploration of the grey areas of morality and ethics?

I think that the tempo with which we are fed ‘information’ has been possibly mis-characterised as ‘evidence’. As a practical matter we don’t have time for a grey area. We don’t have time to get through our day so we’re connected with things that might as well be implanted in our brains. They [the grey areas] demand a lot of attention and we just want to get out from underneath it and so we make very snap decisions to survive and have some bandwidth to live our lives.

At the end of the movie Lydia’s crisis team proposes a re-branding—and then she’s, in a way, exiled to a vague Southeast Asian country. Is she doomed to conduct for comic-con audiences for the rest of her career or is this just a brief time-out for her?

I think she’s making music wherever she can have her instrument, and her instrument is a human instrument. There’s a documentary that I watched, when I was working on the script, about Antonia Brico. She was a formidable conductor, and seemingly had no regrets or a sense of self-pity even though she was completely ghettoised by her gender. But, toward the end of that documentary, they ask her “does it hurt that you’ve had all these years and you haven’t been able to conduct?” She finally breaks, and she says, “You have to understand that I’m a musician, but my instrument is human—I have no instrument, which means that I’ve been silenced.”

Whatever music Lydia’s conducting, wherever she’s conducting, and with whoever she’s conducting, if she can have a human instrument, she’s going to play it.

That’s one of my favourite reveals of the year. Sitting in the cinema it was shocking to see the camera pan to those cosplayers in the audience.

It’s funny. Here’s the thing…John Mauceri just wrote a really interesting book called The War On Music. In it, he talks about the composers who were blacklisted by Stalin, Hitler, and Mussolini, and were expelled and came to Hollywood and started to write movie music. [Music] for movies that Hitler would have been obsessed with, and was—it wasn’t like he was some big devotee to Wagner—he liked movies, and he liked Hollywood movies and those were scored by the same people that he expelled based on antisemitism.

The irony of what John lays out in such a smart way, is that it became a fact that these people were literally ghettoised as composers and people forgot that it was based on antisemitism, they thought it was based on the cultural tastemakers. People like Korngold were totally ghettoised—these really major, major composers—because of movie music as if it was a lower art form. But underscoring movies is no different than Wagner underscoring all the gestures and beats of what he wrote. So why is one okay and the other isn’t? Anyone that’s serious about music today is writing for video games.

That’s where the culture is.

Absolutely. I don’t think it’s any less valid than anyone else. If somebody else thinks that, it’s their own bias, but it’s certainly not mine.

Cate Blanchett is considered one of the maestros of her generation. Was it important to have someone of her prestige take on the role to match that of Lydia?

I didn’t think about her perception by the world at large—Cate, as a performer—I thought about how she was perceived by me. I started writing the script and I could only see her face. She has a sense of humanity, intelligence and wit that’s uncommon.

At points you can really see inside the soul of this character. What did Cate teach you about Lydia that you had never considered before?

Where she really surprised me with this character were in things that I didn’t see when we were working together. Because when you’re working together, you’re tired. You’ve already been working seventeen-hour days. You’ve been putting out fires left and right. No sleep. You haven’t eaten. You’re in terrible physical condition [chuckles]. And Cate, likewise, was working those same hours, then going home and continuing to work. It was really only when Monika Willi, my editor, and I, started to sit alone in Scotland without two-hundred people behind us, that I really started to see things…the tiniest, most precise score of physical actions that she had clearly mapped out, that were just a part of her process I had taken for granted because I was thinking about the much larger sweep. That was a rich experience for Mona and I. It’s very different watching what she does on that TV set over there and watching it in a theatre. In the theatre, you realise just how delicate that performance is.

Yes, it’s powerful. Yes, the character is imperious. Yes, it requires a huge amount of skill set, in terms of Cate learning to do everything from conducting to playing the piano to speaking German to stunt driving. What’s more important is: what did she do with the human being? Those are very small, millimetre choices. For me that was the most surprising thing.

Do you have a favourite memory of working with Kubrick on the Eyes Wide Shut set?

There are many. One of them was running lines with Stanley. Stanley would always do wild lines at the end of a take, because he didn’t want to do automatic dialogue replacement (ADR), something I don’t do either. He wanted it to be in the space and sound alive, so he would run a scene afterwards. The first scene that we did, Tom left and Stanley grabbed me and said: “No, no, just wait…let’s run the scene,” and so I got to play the scene with Stanley. That was the very beginning, October ‘96, and I wrapped in January ‘98. It was nice to see somebody work in a really sensible, practical way. He wasn’t sitting behind a chair and a monitor with someone handing out coffees. He worked his tail off.

What’s your go-to Kubrick film?

It depends on what mood I’m in—it depends on the time of day, of the year. Just the other night I took my youngest child and sat him down and showed him Paths of Glory. Sometimes it’s been Paths of Glory. Sometimes it’s been Barry Lyndon. Sometimes it’s been Strangelove. Sometimes it’s been 2001 [A Space Odyssey]. I can feel him through all of it, but there are different rivers that converge there. I would never say I have a favourite. He wasn’t that kind of filmmaker.

I have to ask—does Todd Field play Monster Hunter?

[smiles] I’m a big fan of Monster Hunter.