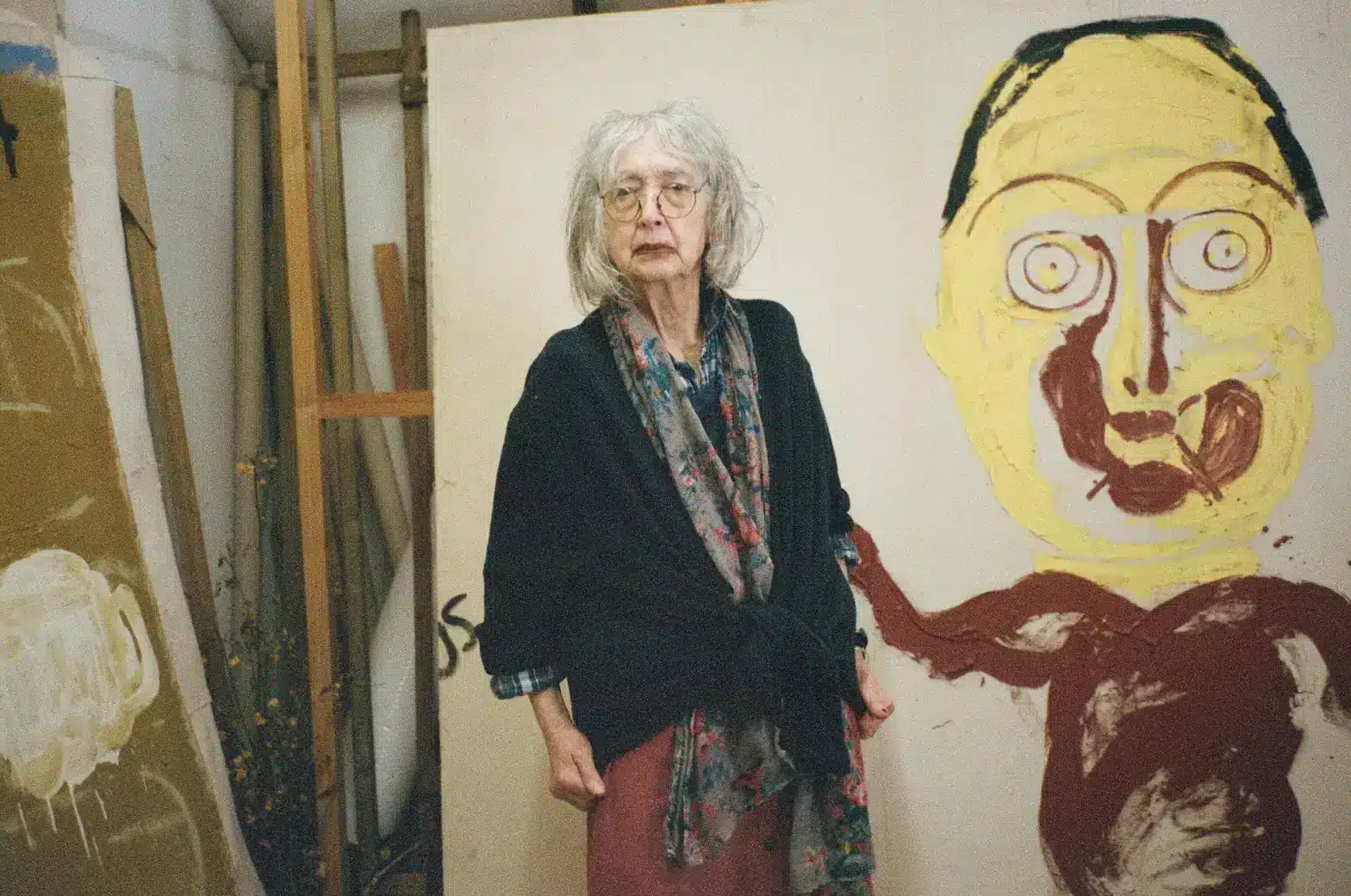

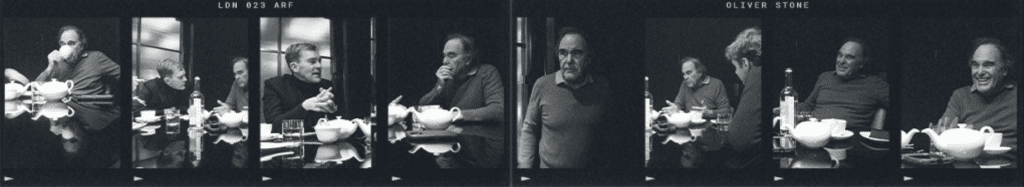

I met Oliver Stone for the first time when he came to London for the premiere of his film about US whistleblower Edward Snowden in 2016. We were introduced by my friend Max Arvelaiz, who in an earlier incarnation worked for the Venezuelan president Hugo Chàvez—and now works with Oliver. But I’ve been watching his films since 1978’s Midnight Express, and followed the political and artistic journey of his filmmaking ever since: through four decades of features and dramatisations, biopic and documentaries.

Oliver has a reputation as a radical filmmaker in the tradition of Costa-Gavras and Pontecorvo. But as a Vietnam veteran and one-time Reagan supporter, his political evolution has been anything but conventional. It flowed from what he learned from experience about the US, both at home and abroad—and perhaps his own mixed US-French background. As Max puts it, “Oliver is an American storyteller with a French sweep of history.”

And in our regular conversations over the last few years, it’s striking how Oliver is still learning. He still reads voraciously and closely follows events across the world—and is of course making films.

This conversation gives some of the flavour.

— Seumas Milne

On Political Motivations

SEAUMAS MILNE

Was the Vietnam War the crucial element in your political shift? It seems to me that you were always a storyteller. Before you went to Vietnam, you wanted to be a novelist and it sounds like being turned down for your novel was the trigger that made you volunteer.

OLIVER STONE

It wasn’t that I was seeking any political understanding, it was just about lying. My parents had lied to me—their divorce proved it had been a lie, so the concept of family had been a lie. Vietnam was just clearly another lie I lived through. It wasn’t about politics. I came back and the country seemed like a mess. Same thing went for Reagan’s policies in Central America.

SM

By the time you made Salvador you definitely had a political angle.

OLIVER STONE

By then, Reagan had been in office for five years. I go down to Central America and there I see another mini Vietnam brewing. American troops were evident and there was no question that they were going to go into Nicaragua, but then it was uncovered through a contractor that the CIA were cooperating with the Contras, and [journalist] Robert Parry, who I deeply admired at the time, wrote a terrific story on it. I began to understand the degree of complicity. I wanted to make a movie about the contractor, and I would say that my consciousness expanded around that period.

SM

So it was after Reagan was elected, not because of your Vietnam experiences. I remember seeing Salvador and the time and finding it electrifying, and of course very political.

OLIVER STONE

Well it was a people’s film first of all. I remember I insisted on keeping this scene where Boyle [played by James Woods] speaks to the CIA in the embassy gardens at San Salvador and he tells them straight out in five minutes what is wrong with American foreign policy, and of course that was the first thing they fought to cut.

On Fighting with the Studios

SM

I read that you didn’t get any distribution from the studios.

OLIVER STONE

We were turned down everywhere. My whole life has been fighting with distribution … it’s never-ending. Salvador was unlucky for me.

SM

Was the reason you couldn’t get distribution with Salvador, but you could with Platoon, was because Platoon was set years earlier, while

Salvador was about events happening at the time?

OLIVER STONE

Yeah. But Salvador also had way too much violence, sex and torture, yet it was far more interesting than they were making at the time about Central America. It was about a real journalist who didn’t give a shit—Peter Boyle—a truth-teller with big swollen knuckles. So, they said no.

But I was a creature of rejection, before and since then. Even Platoon’s distribution company never really committed to the film until they saw the rough-cut. And even then they only put up a limited amount of money for a sixteen-theatre release at Christmas.

SM

But it was massive.

OLIVER STONE

They liked the movie, but it’s a war picture—a downer to some degree. Then they send out the director who is a veteran and you get a lot of press, and it took off on day one. It was hot for six months.

SM

You were saying that JFK was when the trouble with studios started again.

OLIVER STONE

Born on the Fourth of July wasn’t easy either. The studios didn’t want to make that, because [Ron Kovic] is a veteran in a wheelchair who gets castrated. Tom Cruise getting castrated is not appealing to the average American teenager. The film is graphic … the hospital scenes are brutal. But again, it’s because I always wanted to show the truth. My father used to jump on my case as a kid and say: “Don’t tell the truth, you’re going to get in trouble.”

On the Importance of Truth

SM

It sounds like you were having that dialogue with him all your life. So where did the truth-telling urge come from?

OLIVER STONE

The truth itches and you’ve got to scratch the itch.

SM

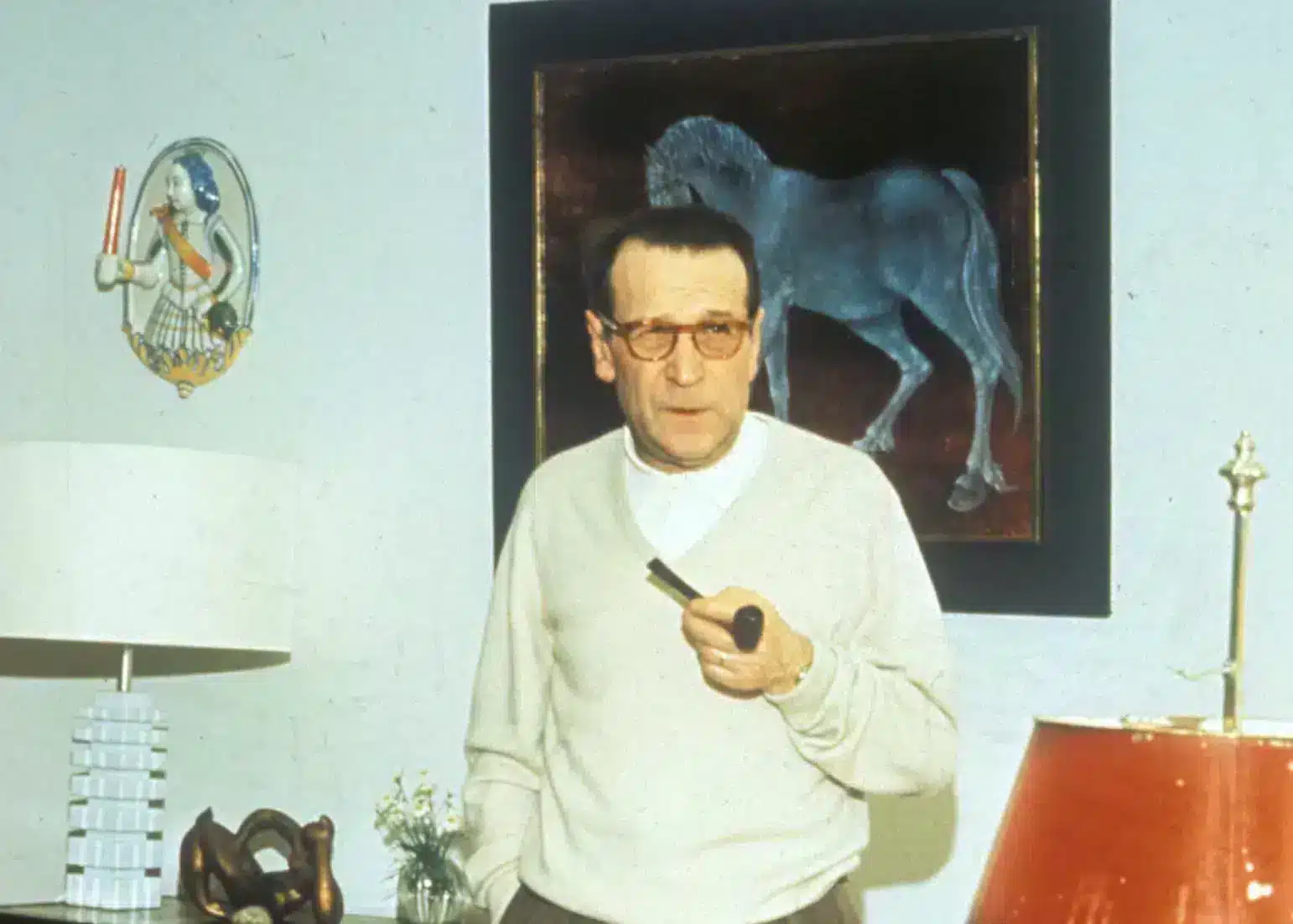

It feels to me, and this might sound like crude psychology, that you come from an outsider’s background in the US. You mum was from France, your dad Jewish-American, and you describe in your book a feeling of being locked out of the mainstream. I wonder if that feeds the truth-telling and the big-picture political dimension that threads through your films.

OLIVER STONE

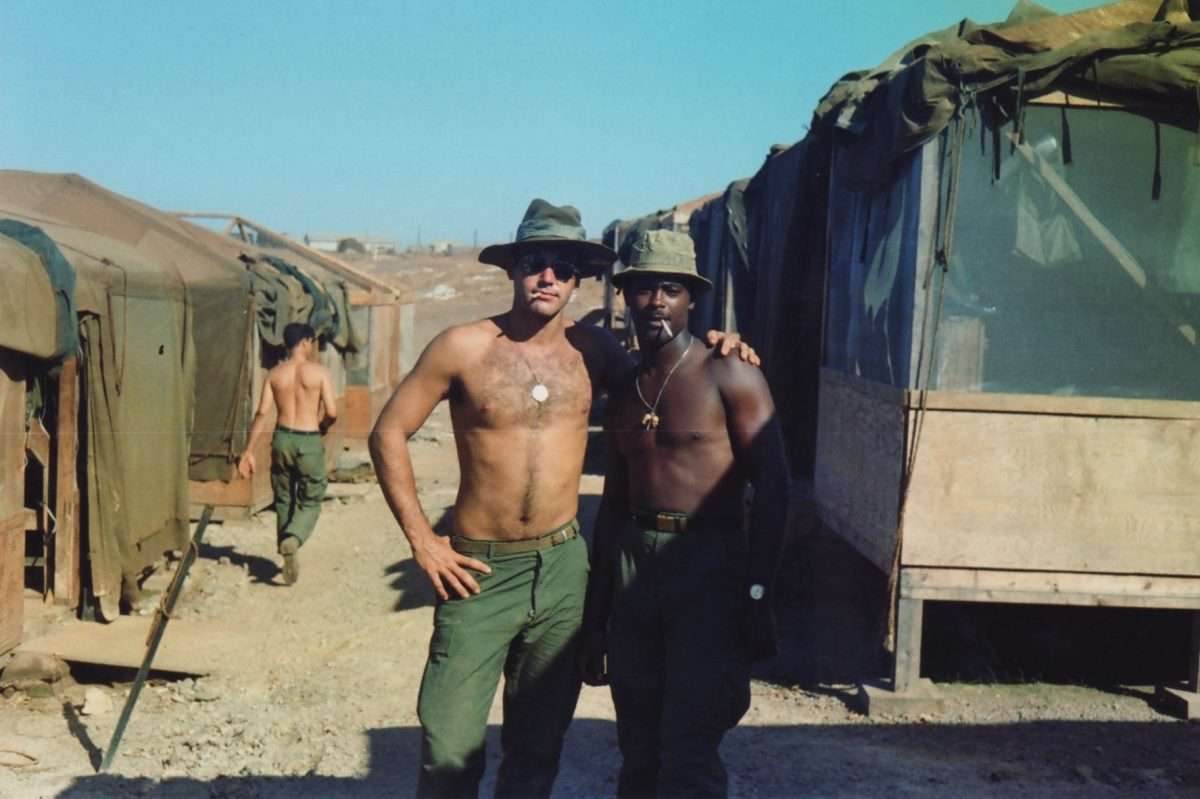

That came later. At school I was a conformist. After graduating, I went to Yale. But then I had an internal breakdown, went to Vietnam first as a teacher, came back, wrote a book, and then the book’s rejected. So when I go back to Vietnam, I want the real thing. I wanted to see as dirty a war as possible.

SM

You were kind of punishing yourself, weren’t you?

OLIVER STONE

I was ruthless with myself. I was suicidal. The whole world had crashed around me when I got back: my parents had divorced and I had nothing to go home to.

I survived and that was surprising, and they threw me in jail on top of that for federal smuggling. The military was brutal, so I got out fast, and I wanted to write about it. I had a version of Platoon very early called ‘Break’—I didn’t do anything with it. Then I kept writing. I was doing a lot of drugs, and writing and writing. I entered a period where movie writing was more exciting to me than book writing. It was a new form in the sixties, European influenced by the French New Wave. I’m half French, so I’m really digging the mix. And I ended up—thank God—at NYU. They encouraged us to take chances. Sure, they gave us cheap cameras, but all this was very lucky. Most American veterans return to their small towns and die there.

SM

To do that, to come back from Vietnam, keep getting kickbacks, struggle to get the first film made, that must have taken a lot of dedication.

OLIVER STONE

Yeah and a lot of rejection. I wrote ten or eleven scripts and really put my heart into it. Robert Bolts [the great screenwriter and Oliver’s mentor] kind of saved my ass in a way. He was English and the English have always been attuned to my work, and he loved a treatment of Platoon I wrote and got me an agent. You need that when you’re getting started.

SM

But it took a long time. Overall it took years to get to the place where you were even writing Midnight Express.

OLIVER STONE

That was in ‘77.

SM

What kept you going? What was the drive to tell stories all about really? I mean, the storytelling seems to have been there since you were twenty-years-old. Originally you wanted to do a novel. Then you decide to do it in films. And your filmmaking trajectory has covered everything from feature films and dramatisations, like Scarface and Nixon, through biopics, interviews and documentaries of every kind, from The Doors to Snowden. And the politicisation came quite late. But the one common thread seems to be the storytelling.

OLIVER STONE

Vietnam gave me the hard material. When you’re raised in a sheltered life going to the private schools, very rarely are you in touch with the ordinary person. Until my parents’ divorce, I was spoiled. So, experience is the most valuable thing you can have, and most of that is rejection. And that’s the world I knew: the world of small Greyhound bus stations, struggling for my weekly paychecks at temp jobs. New York City is also a hard place. It turned very gentrified in the eighties but I remember the sixties and seventies and New York was rough. A lot of reality on the streets hits you in the face, so the people I was talking to … they were all struggling to make it. Vietnam was regarded as a lost cause. People in New York would say: “Why did you go there?”

SM

That’s a reasonable question considering you weren’t drafted. Why?

OLIVER STONE

I thought it was the right thing to do. I also believed in the adventurous Custer books, and the cavalry and Indian pictures.

SM

It’s quite a jump from that to the films you’ve made over the past thirty years.

OLIVER STONE

It is. I’m sure my father wouldn’t recognise me. I think sometimes in life you go to your polar opposite. The question is: did I go far enough? I feel like I failed because I haven’t achieved the political changes I wanted to see. You know, all these films I made hit a big note in America, and I was very respected. But we kept going back to war.

SM

No work of art by itself is going to change events. But they do change minds. I was just reading some academic research on how films can change opinions about and trust in governments, in both positive and negative ways. And there’s no question that those films had an impact on people’s thinking and consciousness, and that feeds into social change. You just can’t necessarily trace it in a measurable way. It’s very rare to have a Zola-style ‘J’Accuse’ intervention that has a direct effect.

OLIVER STONE

Zola did it, but he had to pay a massive price for it—they wanted him dead. You hear about what a hero he was, not the price he paid.

SM

Did your becoming a Buddhist affect how you saw your role and experience as a filmmaker and artist?

OLIVER STONE

That really came around during my next movie, Heaven & Earth in 1993. In the story, this woman uses her Buddhism as a way to overcome adversity, and I admired that deeply, and it helped change my own internal approach to life. It’s very hard for many people to accept, especially if you are an artist or egotistical or selfish. You have to go with the idea that the world is a lot more important than you. Buddhism is a fascinating exercise for living. I’m not preaching it to anyone, but it seemed to help calm me down.

SM

We could all use things like that.

OLIVER STONE

It’s practical. My father used to say, “Nobody gives a beans about you.” We’re just tiny dots, and it helps me understand my place in the universe. But that movie gave me strength. Her strength was amazing—it’s one of my best movies I think. Fuck ‘em if they didn’t like it. Making The Doors was also liberating, because I have these desires within me to fuck everyone, do drugs … the hedonism. I loved that.

SM

That was the same year you made JFK, which you say was a turning point in how you were treated. You were accused of spinning conspiracy theories. But the sequence of events around the murder of Kennedy is, on the face of it, pretty suspicious. You were saying that you didn’t think that way in 1963, but it’s hardly surprising that most Americans still don’t believe the lone gunman story. So it’s ironic that JFK was attacked as a ‘conspiracist’ movie.

OLIVER STONE

The CIA devoted an entire department to Garrison, the DA in New Orleans who wrote the book that the film is based on. But there were so many screwed up details, and it’s an unbelievable case where all the prima facie evidence is wrong. At the time of making JFK, I was shocked to be attacked—and how strongly opposed to any kind of investigation the media were. But surprisingly, the film opened and made a lot of money around the world. So, I realised I’d been through hell and survived, and that I need to continue taking chances. I made Heaven & Earth after that, which of course bombed; but at least I was proud of it. Then I directed Natural Born Killers, which is a very dark satire about the media—who I hated at that point.

On Becoming the Outsider

SEAUMAS MILNE

I don’t think you like the media now.

OLIVER STONE

I like you [laughs] and there are some good media people. When JFK came out I used to be invited to these Washington events; with the National Press Club, and I began to see that the establishment, so to speak, was not so honest. It would’ve been good if they expressed some concern: “Hey maybe Stone’s onto something”, but they preferred to ridicule me. Ridicule hurts, but you’re telling the truth so you have to stick with it. I’ve believed that since school, because I would always back the underdog. I still remember this handicapped kid that nobody liked in fourth grade, and I encouraged people to go easy on him and we became friends. I was nice to him. As a result, I got attacked by my schoolmates.

SM

So you were always pro-underdog. That seems to be the missing link between coming from a conformist Republican family and then suddenly wanting to tell peoples’ stories about injustice and abuse of power.

OLIVER STONE

I even rooted for the baseball teams that were not the best. I was drawn to underdogs.

SM

If you look through your whole pattern of filmmaking, it seems you start with fictional stories and then move into dramatisations, like JFK and Nixon, and latterly more in the direction of documentaries and extended interviews, almost in the zone of journalism.

OLIVER STONE

After JFK, I became well-known all around the world. But when I made Natural Born Killers, I was back to being a bum again, because they tried to pin these ‘copycat’ crimes on me.

The media were saying that I killed people with that film. It was cut to meet the ratings, and I’ve since restored it to the original version for DVD but you won’t find that theatrically. I’m still fighting over this; the same as with Salvador.

I’m always fighting.

Warner Bros wouldn’t work with me anymore … they didn’t finance Nixon because of the controversy. At that point, I became more of a rebel in the industry, which was never a goal for me. I was a famous director, I succeeded. But then I had to fight through the same things I fought with on Salvador for a shot. I became an underdog again.

SM

If these films were not worth making, you wouldn’t have to fight for them. What your story proves is that when you make films like that and you’ve got the power to have a big audience, people try to make it difficult for you.

OLIVER STONE

They [the critics and studios] didn’t understand that I was fighting for my ideas. But my ideas became … suspect. So making Nixon was one of the hardest experiences. I love the film. Anthony Hopkins, who plays Nixon, was delightful. It cost forty-million-dollars and it made thirteen-million at the box office. We thought we had another JFK, but of course Nixon himself wasn’t as popular as JFK. The film bombed. There went my career. Every time I make a film now, I say, “This could be my career”, but I do it, because it’s worth it.

JFK is my apotheosis. It’s the most successful thing I’ve had in terms of fighting the system. Platoon made me more money, and Wall Street did well—even though the studios didn’t want to release it, hardly. Again, they opened the film on Christmas, at shitty theatres, drive-ins. This is a longer beef … I’m sorry to pull it up.

SM

It’s revealing about your journey. I told my son, who is a movie-buff, that we were meeting this evening. He said, one of the interesting things about you is that you had the chance to make films with big budgets in Hollywood while kicking against the system. What you’re telling us now is a correction.

OLIVER STONE

Nixon even had my biggest budget and good reviews. I got nominated for writing—not for directing. The town was turning against me at that time: “Oliver Stone has too many Oscars, he’s a troublemaker … ” Nixon took the wind out of me. My tenth film in ten years, so exhaustion set in. After Nixon I stopped.

SM

You took a break from filmmaking.

OLIVER STONE

Yes, and I returned with [1997’s] U-Turn, which capped off the three crime films I made—including Natural Born Killers and Savages. There were the presidential films—JFK, Nixon and W … but, one second please. I just have to talk about Alexander, which was misunderstood…

On an Unrealised Masterpiece

OLIVER STONE

Alexander [2004] is the most ambitious film I made. But I was unhappy with the original version because the studios got involved. Alexander broke my heart. The reviews were horrible. But there’s a film there. It was released during the Iraq war, and there was a misunderstanding that Alexander was related to that, that he was an imperialist. But it’s the opposite. He sees the Asian side of the Greek equation; he did not want slaves. He goes to the end of the world, places where they didn’t know what was next. It was a huge undertaking and his dream was to unite East and West—a oneness. An ideal globalisation. It was a beautiful idea.

SM

I heard that one reason Fidel Castro was open to doing an interview with you for South of the Border is because he had seen the film, and was an admirer of Alexander. They do feel a bit differently about him in Iran of course.

OLIVER STONE

I put a lot into the movie, but it was misunderstood. It was partly my fault. It shouldn’t have been released.

SM

What was the mistake?

OLIVER STONE

Warner Bros insisted on it being less than three hours and cutting a lot of violence, so the first cut was not me. So, I waited a few years [2007], went back to the original script and produced it for DVD, with a run time of three-hours-and-thirty-four-minutes.

SM

That’s interesting, because the way the media, and social media in particular, has developed, people’s attention span has surely gotten shorter.

OLIVER STONE

You have to let the story breathe. I wanted to register who he was, not betray or cheapen him. He is a political hero to me, because he transcends … he unifies. I wanted Alexander to be my Lawrence of Arabia, frankly. I had visions. It was almost there … in other words, another devastation and that leads to retreat.

SM

You finished your presidential trilogy with W [on George W. Bush].

OLIVER STONE

I think there’s a lot of wisdom in that film. But it’s still incredible the American government allowed a moron like that to become president. When you think about all the devastation, the wars … he said, “You’re with us or against us.” You can’t say that to the world. It’s arrogant, and as a result we destroyed the Middle East in a sense. He was the worst president we’ve ever had. Bush really set an agenda and a whole mindset. Gore wouldn’t have overreacted with Afghanistan. I learned that in Vietnam: everybody overreacts. The moment gunfire happens, people freak out, and people get killed. Try and find out where the fire is coming from before you shoot up the place.

On Having a Dialogue

SM

Your interview films like South of the Border are a different kind of political intervention where you talk at length with Latin American leaders like Chavez, as you did with Putin later on. As a journalist, what I find interesting is that you still produce these interviews in a cinematic way.

OLIVER STONE

I also did Ukraine on Fire which I’m proud of. The reason I go to Castro or Chavez is because they were challenging the American point of view, and saying that we couldn’t get away with everything we wanted to. It was ironic that I’m considering people who run their countries in a tough way—no question—as the underdogs. Look at Castro, I mean to hold an island like that against the US … but people hear about the films and misunderstand. They say, “Stone loves dictators.” I don’t love dictators any more than you do. I don’t like bullies. I hate them.

SM

Then [2016’s] Snowden was your return to feature films—that was when we met with Jeremy Corbyn at the premiere in London.

OLIVER STONE

Yes, he was the sweetest man, and very sympathetic. The Jeremy Corbyn episode must have been very difficult, it was an astounding perversion of the media.

Snowden is about intelligence and cyber-warfare—a whole new concept at the time — and a major violation. The US is still the biggest cyber power in the world … but we’re crying out about other countries using it. We’re the bullies pretending to be the underdogs, and [whistle-blower Edward] Snowden proved that this wasn’t true. He discovered total surveillance and that the government broke the law. And again, no American funding for the film—everything I make comes from abroad. I shot it in Germany pretending to be in America. So here I am, at the end of my career, and I’m having to make

American movies outside of the US. But I’m proud; the film is good. I didn’t compromise—but it was technically difficult because I’m not a computer person. Well … we had Snowden to help.

END