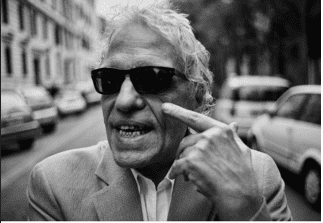

Abel Ferrara sways sideways in his Rome apartment, closes his eyes, sips a bottle of water, and says, “Yo, you hear me? Alright, let’s go.” Of all the contemporary directors, Ferrara could most likely be a character from one of his films—a famously no-bullshit New Yorker with a yearning to walk the wild side. Today though, he lives a much quieter life with his wife and child in Italy. It’s a long way from the worlds he depicted in Bad Lieutenant, The Addiction and King of New York, but Ferrara remains prolific, returning with a recent spiritual drama: the story of Padre Pio. The lionised capuchin monk is half of a diptych of two important spiritual influences (and subsequently biopics) in Ferrara’s life—the first being filmmaker and poet Pier Paolo Pasolini.

In some ways, Abel himself is a spiritual figure. A rebellious art-house director whose battles with drugs and alcohol have been well-documented; a converted, now-sober Buddhist. He’s always aligned himself with street life, but the intellectual and deeply-thoughtful narratives and themes across his thirty-five projects betray more than another New York wiseguy. Padre Pio might be another film in his long body of work, but it’s also about a person going through a change, and that—when you get to the crux of the matter—is Abel Ferrara.

What was your first encounter with a figure like Padre Pio? Is he someone you came upon later in life?

He’s iconic. It’s like, what was your first encounter with Christopher Colombus? My seven-year-old daughter was asking me today about Leonardo Di Vinci, but I can’t remember my first encounter with him or Padre Pio. Especially when you grow up Catholic. When I lived in Naples [while making his documentary Napoli, Napoli, Napoli], his face was always there—like Maradona on the walls. We lived a gangster life back then, and he was the patron saint of every down-and-out, every tough guy…every radical. Like Jesus for the hardcore.

Why make a film about him now?

I wanted to do this when we finished Pasolini [Abel’s biopic about the legendary filmmaker] and because the whole experience with stigmata interested me. Plus he comes from near the same village my grandfather is from in Puglia, born almost at the same time and I wanted to make a film about my grandfather. In a way, this gives me that opportunity.

So your grandfather was religious?

My grandmother was the more religious of the two—she was a kind of a ‘seller of miracles’ herself. In the neighbourhood in the Bronx, they had statues of saints all over the apartment and people would come in and she’d tell them who to pray to, and how much to pay. And these people…believed. They had very specific requests.

Talking about Pasolini and Padre Pio, they both encouraged suffering. They seem like spiritual mentors of yours in some ways. Do you think suffering is necessary?

I’m a Buddhist now, and our stake is that we’re not on earth to suffer. That’s probably the reason I became a Buddhist. Trust me, I did enough suffering, much of it self-induced. If you think suffering is necessary, you’re delusional. At his stigmata, Pio found his true calling, and he became, let’s say, enlightened because of his relationship with Jesus, which is what the film was about—that moment. Because he was struggling and troubled, and he was going through some serious changes. That’s what I related to.

Did the Fransciscan Church give you any backlash?

They were totally supportive. Shia went to the monastery and they took him in, he stayed in Pio’s bed. They loved the film. Anything we wanted they helped with, but most of his stuff, his writing and letters, is out there anyway. We used the actual Capuchin monks in the movie as extras in the movie, too.

Your body of work can be quite provocative, like your start in porn, or the murderous heroine dressed as a nun in MS. 45. Were there any suspicions when you first came together that you would have other intentions?

I’ll tell ya, one of the monks actually told me that a film of mine changed his life; I asked, ‘Which one?’ He answered, ‘Dangerous Game’ [Abel’s 1993 drug-and-sex filled melodrama starring Madonna and Harvey Keitel]. I said, ‘Are you crazy?’ These guys are not what you think they are. They’re very cool. Very cool. Totally open. They know the doctrine, and they live it. They give confession and communion. But they’re not what you think.

Shia found Catholicism while shooting the film. I’m curious to know if you still feel a connection considering the Catholic symbolism in some of your films.

Sure, I started off life as a Roman Catholic. Converting to Buddhism just furthered my relationship with Jesus. It started with a girlfriend. She never called herself a Buddhist, but she was into yoga and being vegetarian—that kind of thing. I’m all into whatever the girl I’m with is into…so I became vegetarian and went to retreats. I was listening to the guys; these big-time teachers she had, and they got me. I understood it in a big way, but I was still drinking and drugging. I would meditate and think I was a great meditator. But then, ten years ago, I got sober, stopped the drinking and the drugging—you can’t do meditation high—and so when you start doing it not high…now I’m getting it. Not quite an awakening experience, but close. It made a difference.

Does it help make sense of your work?

Yeah. It’s like a muscle you use to concentrate and narrow in. Especially living in this world, between the electronic fucking stuff coming at you, and this video-call shit we’re using now. I’m into it all. I mean, I’m not on Facebook or Instagram, but you can’t avoid it. It’s Information City. You get bombarded, but I’m not living in a cave in the Himalayas, I’m on the street bro, you understand? I’m in a practice and regularly going to a program…but who the fuck knows what practice everyone else is performing in?

Is it easier to escape the bombardment outside of the US, specifically New York?

I’m more of a celebrity here in Italy. New York is a grind, it’s all economic data. Unless you’re a billionaire, it throws it off for the regular, normal working kind of people. When I came to New York to begin with, I don’t even think I paid rent. We just did this documentary where I went back to the old places in New York City and I mean, dude, I was living near Union Square, 18th and Broadway—this really beautiful loft. We paid four-hundred-dollars a month. When they were putting it up to five-hundred-dollars we almost burned that fucking building down. The guys living there are paying ten-thousand-bucks a month now. That’s not inflation—whatever it is, I don’t want to be a part of it. Back then, you could make your money and still be an artist.

You’ve always seemed like an outsider in the US. Did you ever feel a part of the American film business?

Today everyone’s an outsider—even the folks on the inside. Other than movies for kids, I don’t know what the film business stands for or where it exists anymore. I guess it exists in the heart of every person who believes in it. But you have to think about the positives—that’s the Buddhist in me talking. If you got a phone, you’re golden. You go over to computer and you have a fucking movie studio. If it was 1935, you were out of luck, bro. You had to go to the studios and you needed the equipment. Even when I was coming up, we couldn’t produce movies that had a synced sound…or lighting: until Kubrick made Barry Lyndon and came up with these fucking crazy lenses, we couldn’t shoot at night in New York.

You don’t think there are too many people trying to become filmmakers?

It’s tremendously positive. But there’s also no excuse to not make your movie.

Can we talk about your early New York films, like The Driller Killer? I wonder if you ever revisit them.

I had a lot more going on and had a different creative mindset. But what we’re doing now [Abel and his frequent collaborators] is similar to what we were doing then. Sometimes I look back and think, why didn’t we just stick it out? But we had this fucking desire to go to LA, shoot on better and bigger equipment and make bigger movies. It is something every American director has to accomplish in their lives. Going to Hollywood is like going to Mecca, and I don’t know why. And so we went, and we got the shit beat out of us, and then we left.

Would you return to Hollywood?

I’m not going to go there and try to take a job now—not unless I’m starving, or if the project requires me to go there. Sometimes, I think, ‘Did we really need to do that?’ Now we’re back making movies like the early days. Tomasso is really The Driller Killer, but without the drill: we shot in our house, with our friends, and there wasn’t a budget. Maybe we didn’t need the middle part of our journey, but I have no regrets.

I read that you crowdfunded for a movie?

That didn’t work. I thought it was going to be a great breakthrough in making money for movies and we put a lot of energy in it but we didn’t even raise 10%. We got to about ten-thousand-dollars, but it was a two-million-dollar movie—it was for Siberia. It still seems like a great idea. People want to see a film get made, and you basically pre-order your ticket based on the pitch and because you dig it. In theory it’s brilliant.

A lot of people are discovering your classic films on YouTube and streaming online. How do you feel about your art being so freely available?

I’m not gonna get bent out of shape about it. People try to tell you these aren’t money-making organisations, but that’s a bunch of bullshit, and these major corporate entities are ripping artists off. It’s just the reality. Should me and my team be getting paid? Of course. I’m also not going to buy the bullshit of, ‘Oh but you get all this publicity.’ Fine. Just don’t rip me off. I can’t control the lifelong distribution of the thirty-five plus projects I made. They’re on their own out there, so I gotta worry about what I’m doing next.

What is next for you?

I have a few different things. When I’m free, I actually don’t watch a lot of movies. I love to read—I know that seems archaic. I often have a list of books on my phone. But I actually got a deal to write my own autobiography. It’s a challenge. I’ve written scripts, but a book is not like writing a script. Still, who the fuck knows? I’ve been reading so many things, especially biographies of different people to help me write it…contemporary guys, like William Gibson, T.C. Boyle; these Americans from my era. Chuck Palahniuk who wrote Fight Club: I like his style too. When is it out? I don’t know. I’ve got to finish it first. But my own autobiography. Crazy.

I suppose you’ll be looking back at the thirty-five plus projects. Do you consider them as one body of work?

Kubrick said that films are inverted pyramids based on one idea. It’s the opposite. A film is a life. It’s got so much to it, and it changes dynamically. Especially when you look back at the people in the movie, what you know about them, who made it with you, and what they did in other films after. My relationship to those people, and subsequently my body of work, changes when I see them elsewhere.

You’re all about the future.

It’s like you said, the past is already out there, be it on YouTube or the DVDs. Some can be tough to find, but people will find a way. You’re talking about The Driller Killer, man. It’s a movie made forty years ago. These films are alive, and they’ll hopefully have a life for another forty years. Well, for God knows how long, bro…

Like this interview? Take a look at our conversation with director Wes Anderson – read here!