Art & Photography, Confessions, Culture

One of the world’s most important war photographers, Sir Don McCullin has captured conflict as a way to reveal the barbarity of war. Our editor Charles Finch met Don at his home in the countryside to discuss the man behind some of the most emotionally-stirring shots in history.

You’re not a painter, but you paint with your camera.

Yes, I’m painting with the light.

Yet you don’t like being described as an artist. Why?

Because I’m a photographer, and I’m quite happy with that title. The trouble is that the art world has crept in on my photographic world. It all came from America—they didn’t think photography was dignified enough for them so they jacked it up and said they were artists.

The inscription that you write on the bottom of a photograph, is that part of the work now?

It’s my part. I met a man who died recently. His name was Peter Beard [the celebrated photographer], and he said to me: “You must write as much information as you can on your pictures” and he’s quite right—you can’t have a picture without an inscription or a title or some reason for it [existing]. After all, photography is a form of information. When I’m gone people are going to find tens of thousands of prints and think “where the fuck’s this?”

I’ve known you for many years and you are a very humble man. I think you share that with many of the great artists I’ve met—the majority of the ones that I’ve liked are all humble.

I don’t know how I’ve been disciplined or what’s provoked it, because to be a photographer is to have enormous discipline. When you get out of bed at 6:30 in the morning, go into that dark room, put your hands in that cold water and chemical, which is dangerous—there must be a screw loose up here to be dedicated to such danger. But I was in such danger in the battlefields, and I managed to crawl back and get here.

Do you think the battlefields have given you a context to appreciate life in the everyday?

Without a doubt. One day, I saw a tank run over a Vietnamese civilian. It was like a carpet, when the tank went by, this man had become that thin. Another day, I saw a man who had been hit in the arse with a bullet and it had come out of his neck. The velocity of the bullet can travel through your body and come out a different place.

Horror.

I’ve seen the anatomy of humanity spilled out on roadways. There was a place called Highway One in Vietnam going to Cambodia, it was the most dangerous place on earth. I’ve seen all that carnage. It’s had an effect on me of course.

Do you think war is inevitable?

Every war I’ve covered I knew in the wings that there was another war waiting to kick off, and I’ve been dead right. There’s no cure for war. Human beings seem to be a warring tribe.

Does it bring out the worst or the best in us?

It brings out the worst of us in the beginning, and occasionally, at the end, it brings out the best.

Would you feel anger when those things happened?

At the time, no, I just thought that what I’m witnessing is exactly what I’m expected to see. You’re going to a war, not some Hampstead Heath funfair. I was alive. Though, during this battle, an army priest came and asked to give me my last rights, and he frightened the life out of me. I said “no thank you father” and he said “as you wish, son”.

Is this in Cambodia?

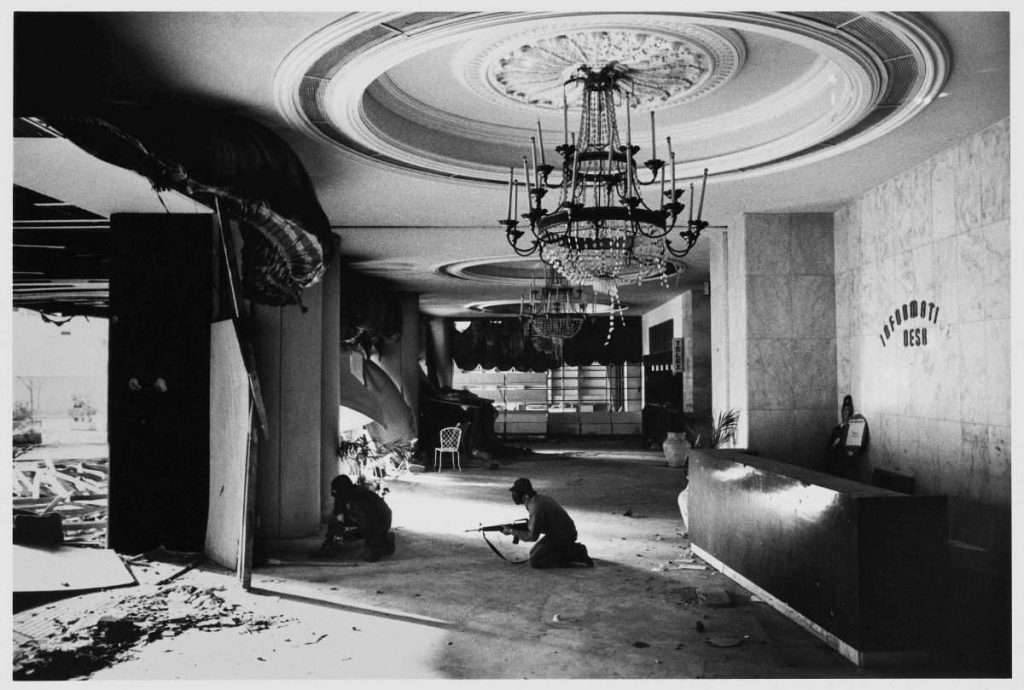

This was a great battle way into the citadel of Vietnam. The Americans destroyed that city. They won the war but destroyed that mediaeval city. They were dropping napalm which was coming towards us; great canisters, almost the size of this room, tumbling towards us. Fixed-wing propeller planes would come straight down, machine gunning and bombing…there was nothing in that city that stood a chance.

Would you get close to the marines? I know that [the legendary American photojournalist] David Douglas Duncan on occasion got quite close to some of the guys…

…Because he was a marine colonel. Before you finish your question, I know the answer. The answer is no, because I wasn’t a marine. Though, I made an exception one day when I photographed this marine who had been shot in the groin, and they had him against the wall—I call the picture ‘Jesus Christ’. I said: “Bring him towards me” and I put my cameras down and I put him on my shoulders and ran away with him. That was the only gesture that brought me closer to them.

He survived?

He survived. They flew him to Guam, and he wrote a letter to his mother in America that said “…some strange Englishman carried me away from the battlefield.” He got better in Guam, he went back, and he got shot in the lungs six months later in another battle.

And how would you feel toward the enemy?

They were not my enemy. No one was my enemy. It wasn’t my conflict. I went there as an impartial witness.

You were never tempted to pick up a firearm or intervene?

No.

Say that you had been in the Second World War, where the adversary was such a clear opponent, would you have acted differently?

Under the Geneva convention a journalist isn’t allowed to carry arms. In Vietnam, all the time I was there, they kept saying “Excuse me sir would you like a weapon?” I said “No, that’s very kind of you, thank you.” But another man did, a man called Tim Page who died a few weeks ago, he boasted that he was in a battle where they were overrun and…I’m glad I don’t have that on my conscience.

Would you call yourself a pacifist?

Yes, I would. Nothing is killed in this house. The only thing I kill around here are the odd bugs with the spray.

I’m looking out of your study and I see the trees…

On a miserable day like this too!

…and I can understand that you need this retreat to find peace.

Frankly, this is my psychiatric place that has healed my [pause] well, not totally, because when I go to bed at night I go back into the most haunting dreams.

So that would be qualified as post-traumatic stress.

Yes, but I’m much stronger than that.

Do you think that photographing nature is a reflection of your peacefulness now?

The thing about me is I photograph the landscape only in the winter where the trees are naked. People have since told me that my landscapes have a touch of war about them. It’s in me somewhere, but I don’t give it any time.

Artistic endeavour in a certain period in a man or woman’s life means it’s very hard to juggle family and career.

Almost impossible. You marry someone and they don’t expect you to be gone all the time and you’re putting your priorities in front of even the priorities of your young children, so in a way I behaved incredibly selfishly.

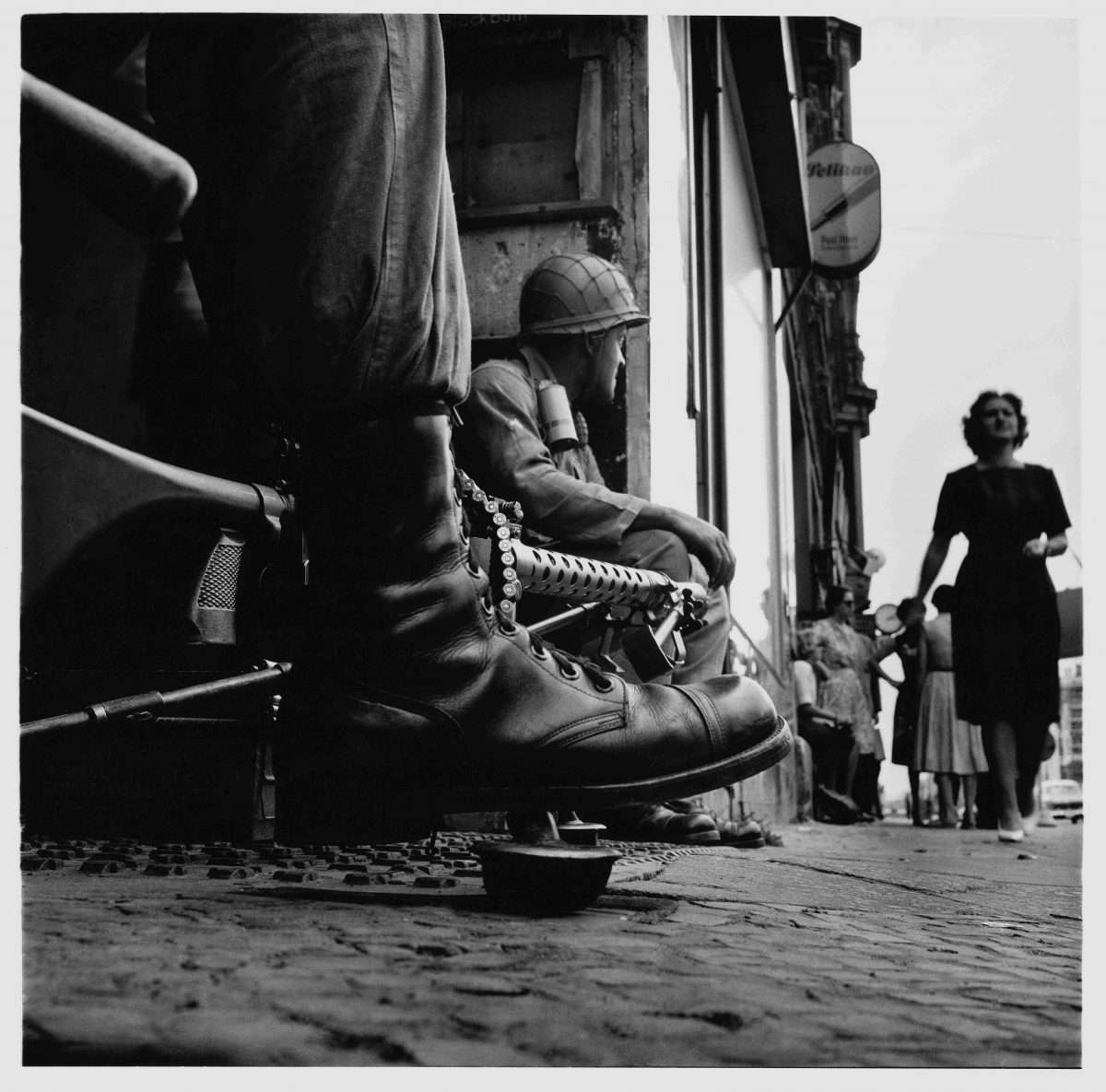

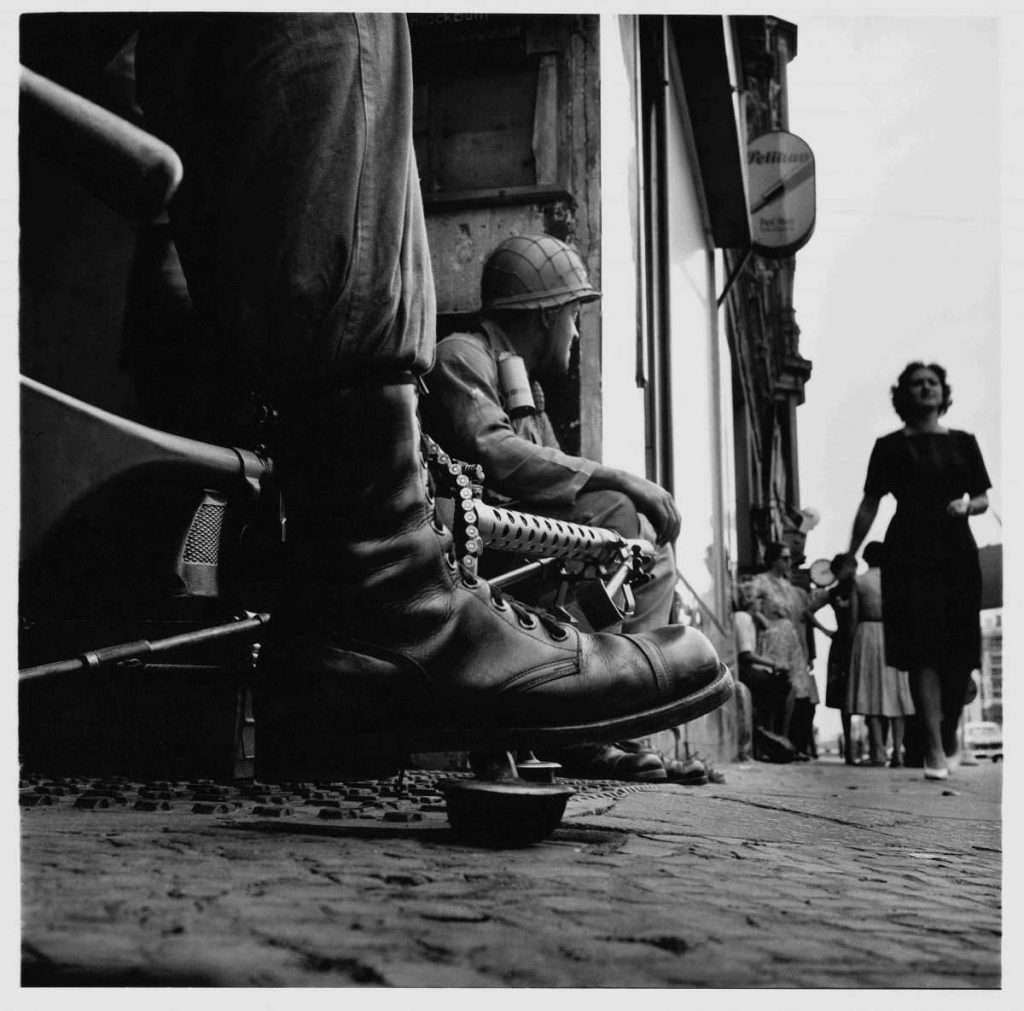

I asked you earlier about some of the most haunting pictures that you’ve done—of course, Vietnam and Cambodia—but I personally find the urban conflict of Cyprus particularly powerful.

Well I think a lot of the pictures I did that were most moving were seeing the terrible social deprivation that was going on in England, one of the richest countries in the world. When I was in Africa or a third world country and they would say “oh you English are very rich” I would tell them how many poor people there are in England, and they thought I was out of my brains. There’s always been millions of poor people in this country, even today. And we’ll all be much poorer from the war in Ukraine because of the petrol and gas that’s been cut off. You don’t get through this life without some struggle—every year there’s been a dramatic struggle for life, and I’m probably a lot better off than most.

Do you ever revisit old works?

All the time, when I’m in my darkroom and I’m bringing up pictures of starving children in the Vietnam war, they’re the most damaging work I did and it affects me personally—because I’ve been a father. Having children of my own, I’d come back to England and my kids wouldn’t eat their Sunday lunch and I sometimes overdid it, but it wasn’t my fault. When you look at all those dying children looking at you with those pleading eyes. What did I bring them? I brought them two Nikon cameras hanging around my neck. I went there and I’ve been very successful in my life, and I don’t enjoy the laurels. I shouldn’t ever have accepted them, but I did.

Do you not think your photographs bring an important debate into people’s homes?

That’s all they brought. They didn’t bring clarity. They didn’t bring finality. They didn’t bring resolution. Every time war ended, another one kicked off. In a way, I feel slightly unachieved in my life. I feel as if whatever I did, some of it was to do with me because I wanted the recognition. I know why I carry the guilt and I know all the answers to the guilt I carry. Not many people do, but it’s important for me to know the ground I’m standing on, and the horizons I’m walking towards in life. Now I’m very close to the edge of that horizon, and I feel like I’m sitting on a crown of thorns, not the laurels.

What were you doing for a living when you first started out?

I was working for an animation studio in Mayfair. I used to photograph the drawings of the artists, that’s all I did, in a very small dark room. I didn’t really know a lot about photography, I knew how to load film and process film, but I didn’t know I had a creative instinct.

But you had the camera that your mother had saved you. Do you remember the very first picture you took with it?

I photographed a gang of boys where I grew up in North London. I only took one negative of that gang standing in the derelict building, but once I showed the observer editor that picture, he asked me to do some more for them. I woke up one Sunday morning and they had published a half-page of those photos, they gave me fifty-pounds. From then, every other week I went and did things for them and then finally the Cyprus civil war came in 1964. I knew the area very well as I was in the Air Force there. I went back to a place called Limassol, and I was the only photographer—there were no other journalists there as they had gone to the other side of the island on a PR trip that day. I drove into the Turkish quarter of Limassol and there was a huge gun battle going on. I zig-zagged through the gun battle, parked my car, and was immediately arrested by the Turkish police and was told that I would need to stay in a police cell for the night for my own safety. In the morning, a bullet struck one of the bars in the cell and I woke up and the battle was in full swing. I ran out with my camera. I had no knowledge covering war, so I was running around like a mad hare.

I went back to England with a roll of film and the Observer published another half-page and offered me a contract: two days a week at fifteen-quid a week. Me and my wife had to rent two rooms in the house I was brought up in, at the top with no toilet. The room I processed my film in was the same room I had a tin bath in which we would fill up with saucers. We had two years of that before we moved out into the suburbs.

When you come back from the unimaginable horror of war, which most people can’t begin to comprehend, what’s the first thing you do?

After that battle in Vietnam, I didn’t take my clothes off for two solid weeks. I had been lying next to bodies. So I went back to the press centre and I had a shower. I took all my clothes off, the whole lot, and threw them in the bin. I had to get rid of the history of those last two weeks. I’m not sure if it was the water of the shower or my eyes, but I think I was weeping. Hotel bedrooms have always been my greatest fear. Because that becomes your cell. That’s where all the memories come out and take the piss out of you—you don’t sleep, you miss home all of a sudden, all kinds of stuff pours out of you. It’s a psychiatrist’s dream, this conversation. It all pours out of you. You’re fighting back your cowardly thoughts. Englishmen don’t cry. If you go to the Middle East, where there have been massacres in villages, they weep unashamedly. Englishmen never show that public grief. So when you’re under that shower and no one’s around you, you do let a few out.

At least you’re not a war junkie.

I guess I was one of them in the beginning, until I saw the dying children. Until I understood what I was there for. I wasn’t there for the Hollywood war that I was weaned on.

Hollywood in the war is an interesting subject because there were a lot of brave people who went and gave up their careers, like Duncan Fairbanks Jr. and Clark Gable and David Niven. They came back and still had to make these movies that were kind of silly. It was hard for them.

The film sets that I have worked on [as an advisor], when you see things that aren’t right and you tell the director, “Well that would never happen,” they say “Yeah ok, we’ll sort that out Don…fuck off” under their breaths!

It seems to me that war is completely uncontrolled.

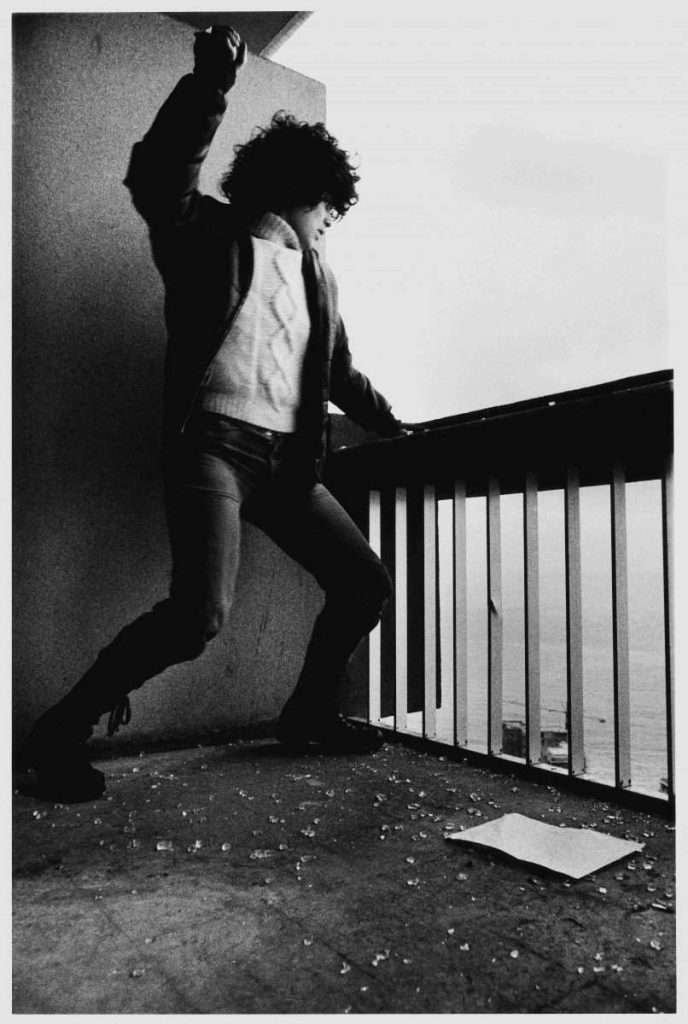

The battle starts and you hear thousands of bullets snapping over your head and you think “Oh fuck. Please God, I promise never to be bad again, please make it stop.” I got into this small village and there were two men lying in a pit—one had had his foot blown off and he’d put a bandage around it, and they were both lying there, flies all over them. I thought “Why am I here?” Looking back, I know why. I wanted to live life on the edge.

But that’s another problem…the guilt of feeling thrilled.