Few moments in the last decade of cinema have had more impact than the foodbank scene in Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake.

Single mother Katie, played by Hayley Squires, cold with hunger and white with shame, hides behind a shelf and tears open a can of baked beans, spooning them down with her hands.

I remember even now the gasp of shock that accompanied the sound of the tin spurting open when the film premiered at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival. It was one of the most astounding moments I’ve witnessed in 25 years at Cannes, the collective sound of the truth of an intolerable social situation hitting home. Such was its impact, it carried the film to winning the Palme d’Or that year and has become a symbol of the cost of living crisis that has now engulfed the UK and many parts of Europe and America.

Now, I’m sitting with that scene’s director, Ken Loach, in the garret-style eaves of his offices in Soho discussing the power of cinema, and of his particular cinema which has engaged audiences, enraged politicians and sparked debate for nearly 60 years.

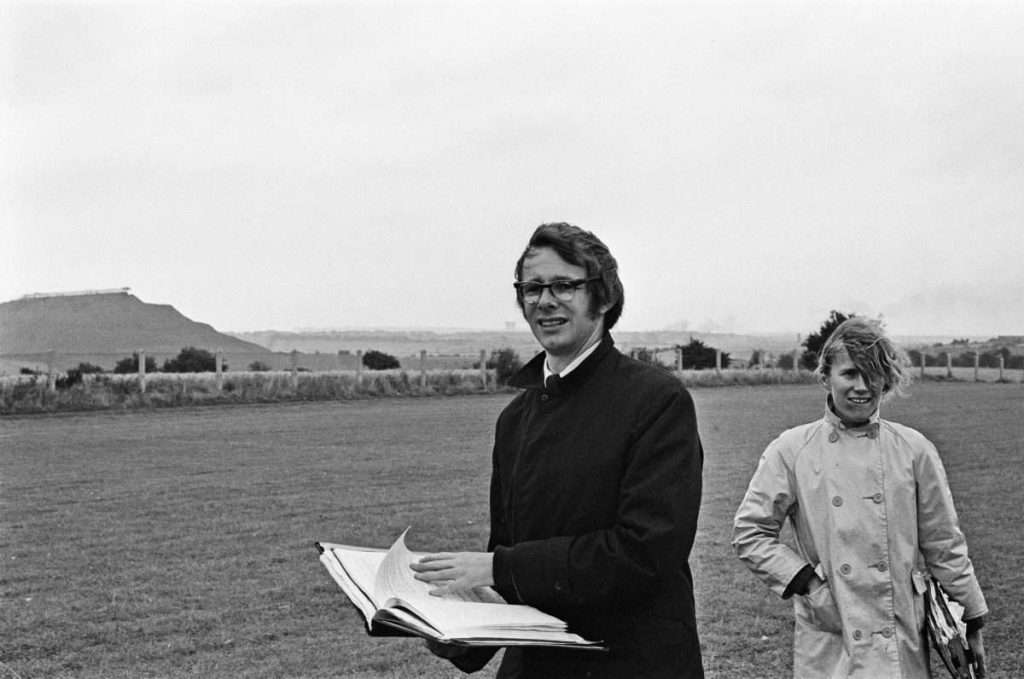

We’re surrounded by the posters of the films he’s amassed, from the face of the young Billy Casper in Kes beaming out at us, to the inter-racial romance Ae Fond Kiss and the hopeful VE day image of his documentary The Spirit of ’45. And we’re talking almost exactly 66 years to the day since his film Cathy Come Home aired as “The Wednesday Play” on BBC 1 (16 November 1966) and shocked the nation into awareness of homelessness and leading to the firm establishment of the charity Shelter, (a body which, sadly, still exists today)while the crisis Loach highlighted has grown to tragic proportions.

With a typically impish yet modest laugh, Loach savours the irony of I, Daniel Blake and that tin of baked beans having any effect at Cannes. “Probably just reminded them to order more tins of caviar to be sent to the yachts,” he scoffs.

There is still no filmmaker like Ken Loach. A member of the exclusive club of double Palme d’Or winners (and the record holder for number of films in Competition at Cannes, with 14 contenders), he remains committed to a style of directing and story-telling which repeatedly shines a light on social issues and human injustices while moving audiences to tears as well as, one hopes, some kind of action.

In a wide-ranging and generously long interview—only granted during his lunch break from the edit on his latest film The Old Oak—we discuss the techniques, working practices, outlooks and passion which keeps him going, and how to harness the power of cinema.

I couldn’t help but gawp at the film posters on your office walls and remember the first time I saw so many of those films and what an impact they all landed with and made on me. Is that your intention?

Well, you want to leave the audience with something when they get out of the cinema, don’t you? Something so they’re not just thinking what are we going to eat, or when’s the next bus home. Cinema should leave the audience with a question, something to consider, or even a challenge—but not in a hectoring or didactic way. And if a film has moved and touched the audience, then I believe that should have consequences.

Do you start with a political point you want to make and then work outwards from there?

In a documentary you present your evidence and say your point directly. But film has to be more persuasive and use a reasonable voice, so in fiction it’s got to be profoundly human, you have to tell stories and put people on the screen who make a human connection to you. You have to be able to read them and share their dilemmas. Because in life, there are often no easy answers, and life is full of impossible choices, and so it’s about sharing those with the implications that maybe we don’t need to live like this. The trap is wanting to make something so clear then you can tip over into being blatant and that’s no good, that’s just bad drama and you lose the audience. Oh, I’ve made some scenes that spell it out, that are too ‘on the nose’ and perhaps we didn’t need to actually say it out loud, you know, when it’s the message of the film…but if it’s urgent, you feel you want to say it and don’t want to miss the moment by being opaque or muddled, so you blurt it out…sometimes you feel you just have to. I was struck from a very early age by Shakespeare and he always got right to the point: there’s something rotten in the state of Denmark—it’s very clear. But if I say there’s something rotten in Britain, well, they say I’m too didactic and too polemical. So, it’s the way you do it, the way you express your point that really matters.

The impact of the food bank scene illustrates that perfectly. It’s such a human tragedy enforced by a social and political situation…

But the Tories still said it was fiction. You see, that’s why you have to make your points through drama. They acted as if I’d made it all up even though we had researched it so thoroughly. And now food banks are practically policy and I’ve even heard them say that they’re a good thing because they demonstrate how generous society can be, that poor people are there to help the middle classes show their charitable side. But if you make it human, nobody can argue with it. So, whenever we make something shocking, I check: if it’s essential in the narrative, true to the character and if it’s objectively true, so all that justifies a scene’s existence, really.

How do you ensure that it lands so powerfully, that it has an impact dramatically?

Well we don’t let everyone have the script so not everyone in the scene knew how it would play out, so their reactions are real shock and surprise. I think if we’d rehearsed it, we’d lose the impact, but you fly by the seat of your pants. But what really broke me up was something else that happened. It’s when the woman at the food bank greets Hayley and she says: “Let me help you with your shopping,” and that’s just such a generous way of putting it, to say that to someone who is essentially begging for food because it leaves the supplicant with dignity. It restores the power of choice to them. That essential respect and sensitivity, well that just floored me. I mean, people are a knockout, really.

That’s an amazing thing to say. And it’s at the heart of all your work, I think. I know people think you make political statements, but I’ve always found your films profoundly human because…well, people are a knockout, really. I mean Kes, that’s the sort of film that changes people’s life, makes them behave differently

Oh well, that’s kind of you to say so. That’s the best you can hope for really in terms of impact, that you touch people and leave them with a hope or a thought. You want to suggest: this is the way the world works, have a look. It’s not a campaign for one thing or another for which we’re waving a flag, it’s always about the ways of the world. It’s got to be a human idea, something that lasts with truths about the way people live together that transcends the immediate issue. So, we try and grapple with the forces that determine how and why things are happening the way they do. All I ask as a film maker is: which side are you on really?

Do you think cinema is still the place for asking that question? Can films still be a tool for change?

Well it’s increasingly difficult. There are so many layers now. When we made Cathy Come Home, there was only myself and Tony Garnett, my great friend and comrade. And we knew what we’d made and we took it to Sydney Newman, Head of Drama at the BBC. And that was it. Sydney saw it the day before it went out, gave it the OK, and he was very supportive of us, and we were off. You’d never get that nowadays. Everything is so micro-managed. TV won’t do it. Streamers will never do it. Nobody can tell a story without layers of executive producers and script meetings where everyone has to have their say, all getting paid to chip in. So, there you are, you want to say something you’re passionate about, something savage and harsh, a story that says “Share my outrage, my disgust and pain and my anger, this is how I feel about it, fucking look at it”. But you can’t. It becomes modified, neutered, the sharp edges all taken off, because the mechanism of production is now so weighted with controls.

I don’t see any directors out there doing what you do and have done. I see your influence, but no filmmakers are telling it like you told it, making movies with impact. Does this mean the corporations have won the war?

All around I see people who are very concerned about the world. Look at climate campaigns, strikers, protesters—there is massive concern. But if someone wants to make a film about this, they can’t. Look, it’s not directors who decide what films get made, it’s investors—they invest in commodities while directors want to make communications. Investors want what will be a profitable commodity and of course that’s going to be something they want said, something to their taste, so they’re not going to fund films against that. Even government funds tend to look to first time directors instead of good pros who can tell their stories. They’ve all got an idea in their back pocket they want to make a film about but nobody will give them the money for it, so you could assume that government support for debut directors comes as a way of exercising a bit of control, in terms of allowing them a voice for the first time.

Where will political filmmaking come from then? Or any drama with politics or activism involved?

I don’t agree you need a political cause to make a movie. It’s got to come out of a shared humanity, first and foremost. Never forget that films that have real humanity and complexity of the human condition, they will always be valid if they’re done with understanding, compassion, and nuance, they will always be worthwhile. The problem with executives and script meetings is that they want you to rationalise something that’s only half formed—you see, making a film is an exploration and you don’t know all the answers before you start. It’s like life, you get the answers at the end…

I don’t want to sound impertinent, then, or suggest that you are at the end, but you have threatened to retire several times and you’re still here, still making films. Why? And I’m not sure if younger people seeing a Ken Loach movie for the first time—like generations did with Kes, or with Ladybird Ladybird, or with Looking for Eric and then with I, Daniel Blake—know it’s the work of an 86-year-old director. Most maestros near the end of the career contribute a ‘late masterpiece’ or something autumnal, or reflective. Yours aren’t like that. I don’t know The Old Oak yet, but I assume…

It’s about Syrian refugees in an ex-mining town in County Durham…

So, you see, nothing autumnal about it!

I hope it’s got energy and vitality and I’m certainly not sitting in a garden chair waiting for falling leaves. I can’t imagine doing something autumnal, there’s just so much that makes me feel I need to make it, I wish I had another ten years…But it’s exactly what I was saying: exploration. I didn’t know anything about Syrians, really, before beginning this film but I found out everything while making it and it’s the little moments of generosity that you’d never appreciated, that aren’t in the script, can’t ever be. It’s the people who surprise you and you have to allow the space for that to happen, and that’s what’s human and it absolutely touches you every time. Yes, the basic story is written, always with great empathy and insight by Paul Laverty, my writer, and it’s always the economic situation of a certain time that drives people into a certain situation, but it’s always the people when you find them who bring that to life.

Because your films do have a lot to say, they’ve taken a lot of abuse over the years. If one of your films doesn’t get attacked, has it failed?

An independent film is a small voice in the chorus of public discourse. But there are power structures in place that endorse the oppression of the worker and which endorse the priorities that produce poverty. I have a duty to point that out. But I always learned to do your research thoroughly because it will be challenged, and they will accuse you of making it up as fiction, and there will be hostility. Like the Tories who said food banks weren’t there. After Cathy Come Home, Mary Whitehouse was right onto us the next day. I’ve been called The Man Who Hates Britain, when we showed what the British did in Ireland, closing down Parliament and the press and sending in troops, the abuse I got for showing that, in The Wind That Shakes the Barley—my word. They said I was a worse propagandist than Leni Riefenstahl; the columnist Simon Heffer said he didn’t want to see the movie because, and I’m quoting: “I don’t need to read Mein Kampf to know what a louse Hitler was”. Me, compared to Hitler? Imagine that. And when I made the Spanish Civil War film Land and Freedom, that film took abuse from the Stalinists because we’d criticised the Communist party…

That’s what I’m saying. People think your films are exaggerated and partisan to make political points. Although I always tend to think of the little moments of comedy in your films, the bits of banter and camaraderie in films like Riff Raff with Ricky Tomlinson, or Sweet Sixteen with Martin Compston or those lads stealing the whisky in The Angel’s Share, or with Steve Evetts and Eric Cantona in Looking for Eric.

I do like those moments of humanity. And that’s the exploration of film making for me, to find those connections. And it can work because we’re tight team of writer, Paul Laverty, producer Rebecca O’Brien and myself and we’re all mates and we never make a film without all being absolutely united in what we’re going to say, all committed to the basic premise — so that it’s in the bones of the movie and if you all share those motives and head in the right direction of the premise, then you can work towards getting those moments of truth and reflect on our understanding on what are the defining conflicts of the time. I’ve never had a trailer on a set. I don’t believe in them, I would hate it, they’re hierarchical, exactly the opposite of what we’re working towards.

Given that so few film makers now make films like you, do you have advice for aspiring directors?

I don’t want to put anyone out of a job, but I wouldn’t do these courses in script writing or film making. Just put on a play. Who’s going to teach you more about drama, the light and the shade than Ibsen, Chekov, Strindberg, Shakespeare, Moliere? Seriously, put on a play, direct one, hire a small space. You will learn everything about the pace and rhythm of drama and the structure of telling your story.

It strikes me that even your acting alumni go on to have very impressive yet very modest careers, even the most famous of them. Hayley Squires, Martin Compston, Robert Carlyle, even Cillian Murphy, they can have big hits but they’re all very grounded as far as stars go. Is that something you distil in them?

Oh, I think it’s why I chose to work with them in the first place. There’s a seriousness and integrity about them and you know, we do stay in touch with them all. I see Billy Casper from Kes quite often and he’s in his 60s now. Bobby Carlyle, we speak on the phone from time to time, Cillian, he’s a lovely man, Hayley, too, I’m thrilled she’s doing so well. I mean we’re not all talking daily but they’re in the diaspora of my good friends. I won’t take any credit for their success, but they’ve all kept a certain dignity in their work and I’m very glad they have. We all should, really. That’s probably the best advice I can offer anyone, in film, politics, or life.