When Ernesto Chahoud gets out the Swedish-made, Egyptian Port Said submachine gun from behind the counter and thrusts it into Anthony Bourdain’s scarred hands, that’s when the film crew get a little twitchy.

It’s March 2015 and Tony (the late chef, documentary maker and a dear friend), Ernesto (big-haired Lebanese DJ of Beirut Groove Collective fame named after Che Guevara, whose father opened the joint we’re in), and myself (writer, poet and Bourdain’s companion in Beirut) are in Abu Elie’s tiny Communist-themed hole-in-the-wall bar shooting a conversational scene for the last Beirut programme we made together: CNN Parts Unknown Beirut.

Now, I say Communist-themed bar but it’s no theme. The Red Knight, or Naya’s bar, or Abu Elie’s, as it’s affectionately known by the patrons, is where Lebanese leftists of all stripes have been drinking for decades—politicians, fighters, musicians and writers—and it’s one of the best spots in the city to get properly drunk and set the world to rights.

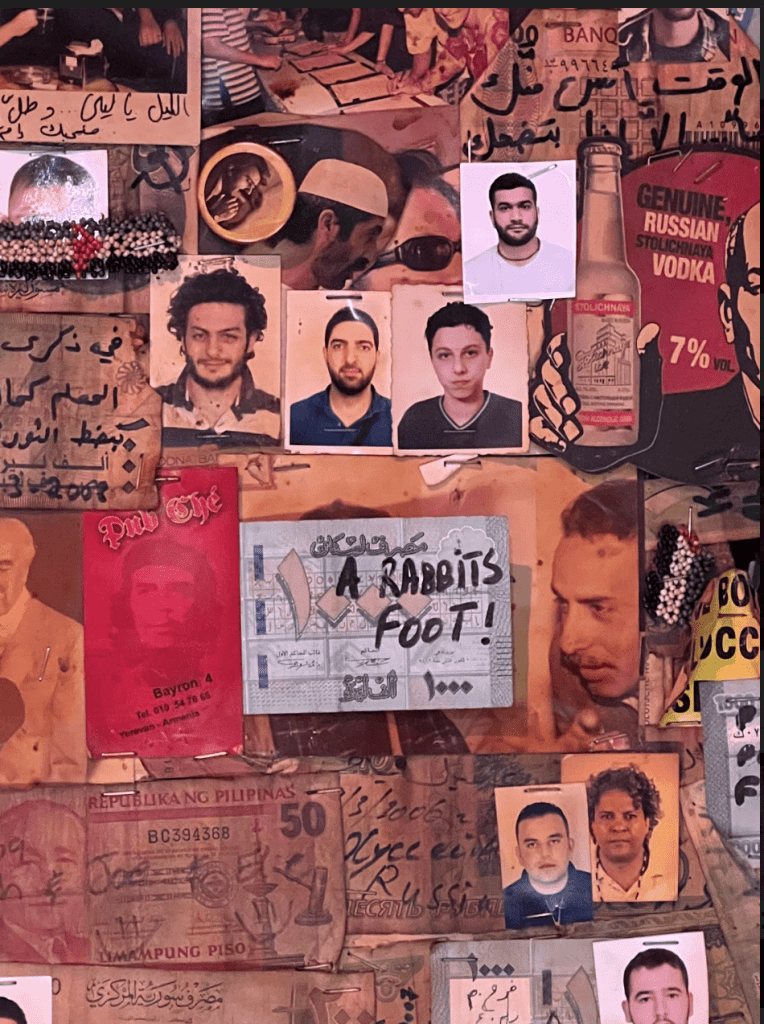

And we’ve been drinking. A tasty cocktail of whisky and vodka shots, plus Tony’s favourite, arak, Lebanon’s version of pastis. And as the liquor flows, so does the discussion: from the bar’s décor of socialist flags, images of Communist Arab leaders and posters of Guevara to Beirut’s construction boom and the Syrian war just 140 km away on the eastern border. This was of course before the 2020 port explosion and Lebanese banking Ponzi scheme that has left the country in deep crisis—the latest failed state of the Middle East today.

Naya Chahoud, one-time Lebanese Communist fighter during the Lebanese Civil War and against the Israelis in the seventies and eighties, opened the Red Knight as a private club in the Caracas quarter of the city after the war ended, essentially as a place for his friends to hang out. In the nineties and early noughties, this humble place became a hub for intellectuals and artists. Songs were written (and sung!), debates were had (arguments too!), mezze was eaten, and drinks were drunk. Everyone from the Lebanese musicians Ziad Rahbani, Sami Hawat and Khaled el Haber to the assassinated publisher Lokman Slim, legendary Indian icon Ravi Shankar—and even the son of Che Guevara and the whole Cuban Embassy in Beirut have stopped by.

And if Naya didn’t like the cut of your jib, you weren’t getting in. He once refused entry to George Galloway because he didn’t fancy his loud voice. For the last decade, after his death, Abu Elie’s has been run by Naya’s wife Therese Saade and it remains as popular as ever. Though open to the public there’s still the sign that says ‘Private Club’ on the door.

But back to 2015.

“So, what’s with the ammunition on the walls?” Tony asks Ernie.

“Hah! Those are from the Civil War. My dad used to fight for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and when he stopped and opened the bar he kept some bullets,” Ernesto replies.

“But that’s nothing. You should look at this,” he continued, ducking down behind the bar.

And out comes the Port Said. “Check this out, this is an original,” he adds.

I automatically jerk back as Tony takes the gun and Ernesto points out the magazine and bolt-mechanism. In our inebriated state we look over it bemused while the film crew in the corner are manically whispering, “He’s getting out the gun, he’s getting out the gun. Don’t panic!” But Tony was cool as a cucumber. He had been in far more trying situations than this on his travels for Parts Unknown, and clearly realises there’s no danger.

Close up, it’s clear the gun is at least fifty-years-old, rusting and looks more like a prop from an Indiana Jones movie than a functioning firearm. Ernesto disappears the gun, and we raise our glasses of arak shouting “Kesak,” the local word for ‘cheers’ while the film crew relaxes. Really, I think, what did they expect? This is just another night in Beirut after all. And it made for great TV.