Track I: The Coincidence

When Bob Marley came to London, he lived at number 42 Oakley Street in Chelsea. This happens to be a lucky number for me—and is one of the many coincidences that led me to the point where I am now directing a biopic on Bob.

How do you make a film about somebody as revered as Bob Marley? As silly as it sounds, I had to go back to the beginning. My middle name is Marcus, after the activist Marcus Garvey—who was certainly somebody that Bob read, and who similarly believed that Jamaicans had a mission to return to the motherland, to Ethiopia. My father purposely gave my brother and I revolutionary names, which is strange to think about now that my Dad is gone, so maybe the writing was on the wall from the start. Along with this, Bob died the year I was born, which I feel holds some significance, and right after I made my first film, Monsters and Men, I came here to London to shoot a television show, and of all the episodes I directed were partially set in Jamaica. I stayed at the filmmaker Kevin MacDonald’s house on the island, and he had shot the 2012 Marley documentary. It was the first time I saw the film—and this was before any script.

The script finally came to me while I was editing King Richard. I didn’t go looking for it, and the first thing I asked the producers was whether they had the rights to his music. When they confirmed this, I said, “It doesn’t matter what state the script is in at this point—because the music tells his story.” Bob Marley sang about his life, and although most of us have no understanding of the meaning behind his words, on the surface we connect to those addictive melodies. It’s ‘rebel music’, reggae music—and the film is an opportunity to try and understand the music and to understand the man, because that’s what he’s pouring out to us.

Bob was thirty-six when he died, and although he accomplished much in his short life, he grew up dirt poor, estranged from his father, in an area of St Anne’s that nobody comes out of with much success. So, how do you go from a beginning like that to becoming one of the greatest living musicians of all time? That story in itself is nuts. I mean, you can go anywhere in the world and people recognise Bob Marley, and that’s what was most fascinating to me: how can you idolise someone, know their music but have no clue as to how they got to be who they are? Bob was a beautifully striking lion of a person…but he’s almost a messiah figure. To many people, he’s a god. But he was also a man who walked the earth. He had the same vulnerabilities as you and I.

I’ll admit that because of Bob Marley’s global reputation, it felt like a risk making this film. I know a lot of people who wouldn’t touch it. But as my Dad used to say, “Don’t start stretching when the coach calls your name. Always be ready.” Maybe I’ve just been preparing for this for a long time and didn’t realise it until now, and sure I have the same butterflies and nerves as any athlete getting ready for a game…but I also feel excited. To tell Bob Marley’s story is an adventure.

Track II: Who Was Bob?

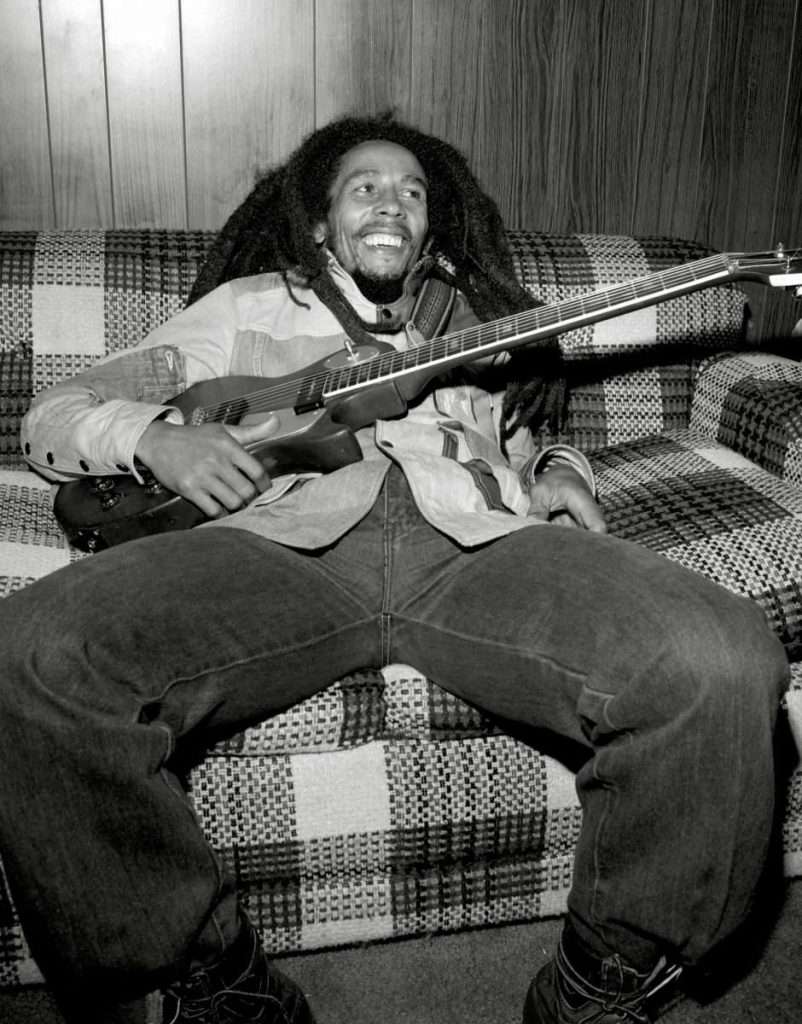

Like all of us, Bob had his indiscretions and transgressions, and we’re looking to present a balanced version of them for this film. Obviously, we’re trying to tell a man’s life in under three-hours—get to the essence of that with actors, and inevitably we’re going to take liberties. But while researching, I wanted to know what it was really like being in a rehearsal session with him and how he interacted with the band; the psychology behind the icon. Apparently, he was the first on the bus and the last to leave. Football was one of his great passions, and I think he trained his musical muscles in the way a football player would train for a game, and I’m sure was aware of this. It wasn’t an accident that he had such a strong work ethic or that he didn’t have an ounce of fat on him. He cultivated his mind, and it had an effect on the way he became respected by the people around him.

One thing I’ve noticed while preparing for the film is that Bob was never really alone. You can’t picture him by himself, and he earned a reputation as the Leader of Men. His followers have remained loyal to this day, so it became important for me to visit Jamaica and meet with them. I had the opportunity to spend time with those that were in the room the night that he got shot. Skill Cole, Cindy Breakspeare, Diane Jobson…we met so many people. They told me he would write songs just by listening to conversations—he would hear the dialogues, what people were discussing, and what was on their consciousness. But even though the public’s voice influenced his songwriting, I don’t think Bob would consider himself political, even though it feels that he is political to us. He was political in his individual fight for freedom. That, in and of itself, was an act of rebellion. But he never chose a side, and always, for all of his interviews, it’s amazing to see someone who stayed out of politics but drove directly through it.

People wanted to kill him because of his relationship with the Prime Minister at the time, Michael Norman Manly. The Smile Jamaica concert in 1976 is essentially around the time our film begins, in between a power struggle between the Jamaica Labour Party and People’s National Party and Bob was in the centre of it all. He didn’t choose sides, which is why a lot of folks think he got shot—because he had so much influence in the country that he could sway public opinion. In that moment, external powers wanted to politicise the concert, and Manly ran his campaign off the back of the very event that Bob performed in, so it would have appeared as though he had picked a side. That night, although four people got shot, thankfully nobody died. They all performed two days later, which only heightened Bob’s spiritual messianic image.

I think his deep beliefs in Rastafarianism are almost unlike any other musician in our time. It’s a religion that was founded in Jamaica in the 1930s that accords key importance to Haile Selassie, the then emperor of Ethiopia. It is not often explored in cinema, and it has a mystical nature from the outside. He was a deep practitioner of the faith, but in his own time, it wasn’t perceived as cool as it is depicted now. Ganja [marijuana] is a part of the Rasta religion, and it wasn’t legal in Jamaica back then. They were considered the bottom-rung of society. They weren’t supposed to be global musicians. But when you hear him speak with such clarity of mind and thought and spirit, you realise that he’s operating on another level. He should be a politician.

Track III: Knowing Bob Marley

To think that Bob left us at thirty-six-years-old, what he gave us, and what he still gives us proves that he was in a league of his own. He was for the people. However his message got out—and this is my opinion—he also felt an obligation to take care of those that entered into his life. Those who I’ve spoken to about his London days talk about Oakley Street being a community centre. You had a food bank at his house and Rastas living there, coming and going at their whim. Bob opened his life to anyone, and what I felt while investigating this movie was that a lot of the folks in his life are still protective of him and his legacy. Everyone we spoke to said, “I was Bob’s best friend.” Everyone wanted to claim him, so to speak. He had that deep sense of loyalty from so many people, and he somehow had this ability to make them all feel like he was theirs. Whether it was speaking to him for ten minutes, hearing him in concert, or spending a lifetime together—everyone felt connected on an entirely spiritual and energetic level.

His music also continues to be transcendental. He was able to take other people’s pain and turn it into joyous songs that we can dance to. He converted his own pain into happy, melodic music. But his words conjure an image of devastation, saying to the powers-that-be: “Look at what you’ve done to my people. Look at what your politics have done to them.” To then put a beautiful rhythm over those words is genius. And he was conscious of his ability to do that.

Bob was not the best singer. He was not even the best guitarist, let alone musician. But he was one of the most prolific lyricists of all time, and consequently he became a global star. He did that by tapping into his imperfections—which is something we can all relate to when we listen to his music. When all of his own imperfections come together, they create something magical. It’s alchemy…his ability to marry all the ingredients and navigate the spaces that we couldn’t, while speaking for the people who had no voice. That was Bob Marley.