For filmmaker Bart Layton, the best movies have always lived where drama and reality collide. And with booming L.A. crime caper Crime 101, he’s pushing that collision in an exciting new direction. The engine behind it all, he tells A Rabbit’s Foot, is the big screen itself.

“There’s something that happens on day one of shooting when everyone knows we’re making a movie, not something that’s going straight to streaming,” says the London-born director Bart Layton, known for his acclaimed hybrid docudrama American Animals (2020) and his award-winning first feature The Imposter (2012). “Every department is in a different headspace as a result. You think about space differently. You think about how you can really earn a close-up. I began to obsess over transitions, how to take the movie from loud to quiet, bright to dark. The big screen brings a responsibility that everyone becomes invested in.”

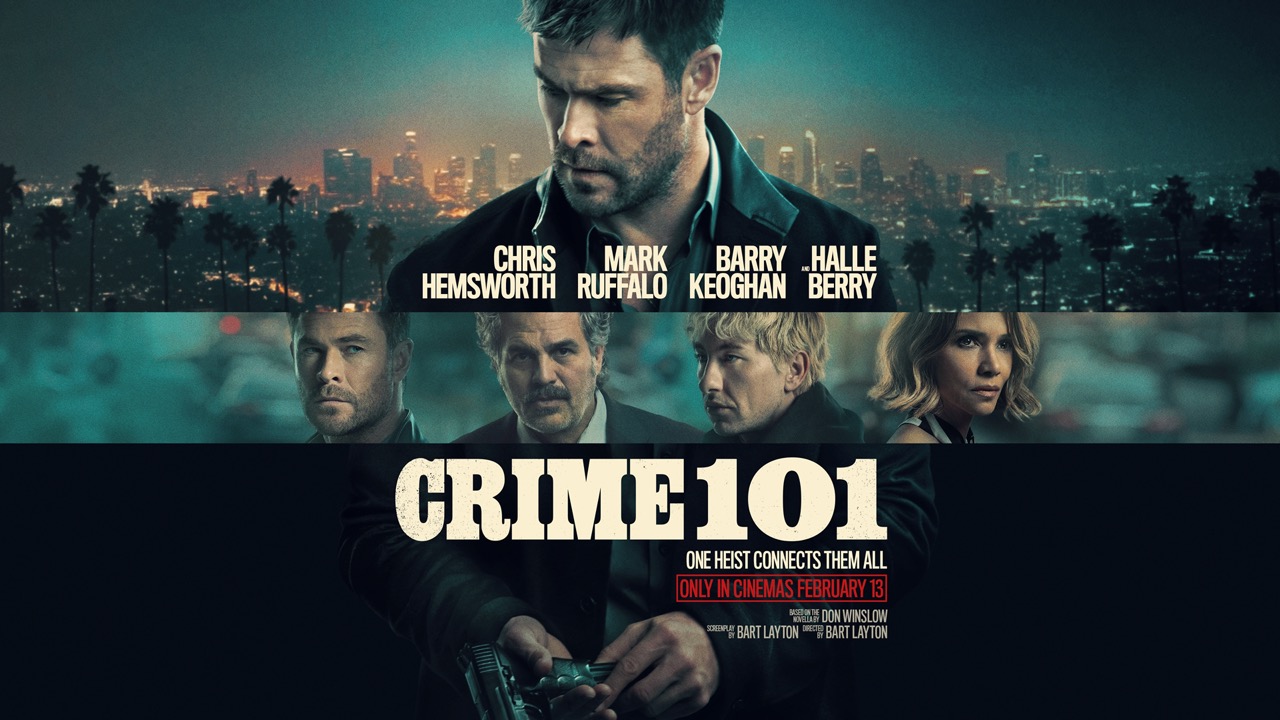

A star-studded adaptation of Don Winslow’s 2020 novella of the same name, his debut narrative feature Crime 101 twists and turns like the California highway it’s named after. The film weaves together the lives of Davis (Chris Hemsworth), a shy but notorious L.A. thief; jaded LAPD detective Lou Lubesnick (Mark Ruffalo); trigger-happy criminal Ormon (Barry Keoghan); and insurance broker Sharon (Halle Berry), each navigating parallel paths of ambition, deception, and survival that gradually merge into an interconnected journey from the gritty underbelly to the glamorous hills of Los Angeles.

Talking to Layton, it quickly becomes clear that he doesn’t just feel a responsibility towards audiences, his cast and crew, and the big screen itself, but to the giants whose shoulders he and Crime 101 are standing on—filmmakers and films that contain thrill and substance in equal measure. The film acts as Layton’s love letter to the kinds of crime films he grew up watching: testosterone-fuelled but introspective thrillers that live in the grey areas of their flawed anti-heroes’ psyches. Those with a keen eye for the genre will see traces of Michael Mann, the classic Steve McQueen thrillers Bullitt (1968) and The Thomas Crowne Affair (1968), and the legendary William Friedkin all over Layton’s directorial fingerprints (during our conversation, he recalls being “summoned” to Friedkin’s house, where the beloved but infamously thorny director clued him in on how he filmed his influential chase scenes.) “There are movies you watch and enjoy, and then there are movies you participate in,” Layton says, clarifying beyond a shadow of a doubt the kind of film he wanted to make and the kind of audience he wants Crime 101 to find. “Those are the ones that change your heart rate.”

Like the best L.A. crime thrillers, the City of Angels looms large over Crime 101’s narrative, with Layton using the structural layout of the city itself to critique its glaring but much-ignored wealth disparity and its unhealthy obsession with status. “You can live in L.A. and glide between your beautiful home and marble office without ever touching the underbelly,” he says.“The rich live literally higher, in the hills or as far west as possible. At the start of the film, a diamond travels from downtown L.A., from an immigrant family, to Calabasas. In the 45 minutes it takes, it quadruples in value—just by virtue of moving closer to wealth.”

A Rabbit’s Foot sat down with Layton at London’s iconic British Film Institute to discuss interviewing real criminals in preparation for Crime 101, turning Chris Hemsworth from an alpha action hero to a socially anxious diamond thief, and why he’s bringing big ideas back to the popcorn movie.

Luke Georgiades: This feels like a movie that was built with the big screen in mind. Are you conscious of that during shooting or is it instinctive?

Bart Layton: It’s a funny one, because there’s a certain kind of movie I grew up loving: films that weren’t franchise-driven but were smart, grown-up, entertaining, and smuggled something thoughtful beneath the surface. They had subtext that felt valuable. I go to the cinema now and wonder where those films went. They still exist, but it’s become rare to see them out there on the big screen.

I felt strongly that we still need those offerings for adults in cinemas. If I’m going to make a movie of scale, with all the trappings that come with that, it should really be for the big screen. There’s something that happens on day one of shooting when everyone knows we’re making a movie, not something that’s going straight to streaming. Every department is in a different headspace as a result. You think about space differently. You think about how you can really earn a close-up. I began to obsess over transitions, how to take the movie from loud to quiet, bright to dark. The big screen brings a responsibility that everyone becomes invested in. I spent most of my early career in television, but the dream was always to live on the big screen.

Bart Layton. Image courtesy Amazon MGM Studios.

LG: How did interviewing real thieves for this film change your perception of them?

BL: For me, one constant sense-check when writing is asking, have I crossed into something too movie-ish? But the irony is that when you speak to real jewelers and thieves, the stories they tell are so unbelievable that if you put them in a film, audiences wouldn’t buy it. I spoke to jewelers in LA who had unbelievable stories of being held up, not just at gunpoint, but really clever heists that they were the victims of. The aim was to deliver everything you want from a fun night at the movies—a great cast, suspense, spectacle—without letting it drift into fantasy. There are movies you watch and enjoy, and then there are movies you participate in. Those are the ones that change your heart rate. You lose that when you go too far into Hollywoodland—you stop having skin in the game. During our car chases, the camera stays with the character. You’re experiencing it as close to reality as fiction allows. We’ve seen the version where Chris Hemsworth is the perfect stunt driver. What if he were a bit more like you and me?

LG: At times his character is that suave archetype that you often see come out of Hollywood, and at others he’s almost childlike in how socially awkward and reclusive he is. How did you want to balance those two versions of himself—is one a mask?

BL: It’s absolutely a mask. When he needs to seduce insurance workers into giving him information, he steps into that confident role. But when he’s just himself, you see that he’s just a kid who isn’t brilliant at establishing or maintaining relationships.

Chris and I worked a lot on his physicality. He’s naturally a very alpha guy. It’s hard when someone has that kind of voice and presence, and you want to see the vulnerability. The most surprising thing about the film is seeing Chris transform into this slightly frightened kid who grew up in a quite precarious situation. You see it in his posture, the way he moves, his cadence, how he interacts with the world. Chris is an exceptional actor and I don’t think the world has really seen what he’s been capable of until now.

LG: Does casting someone so associated with an “alpha” like Thor allow you to play against expectations?

BL: Absolutely. It took Chris a while to feel comfortable operating outside the bulletproof-hero mode. Some people might want the Extraction version of him, and there’s fun in that, but it’s not real. Most of the thieves I spoke to shared a common thread: unstable homes and a lack of adult love growing up. That’s real. We built the character directly from those testimonies.

LG: You’ve said many of the criminals you interviewed didn’t want to hurt anyone.

BL: I worked on a documentary called The Puppetmaster, and that criminal was genuinely evil. But most people I’ve met weren’t. For them, their objective isn’t to damage people—it’s about getting money, fast. You meet people who in most scenarios you would cross the road to avoid, but most of those people have had a rough time. No one has ever given a shit about them, so as a result, it has become hard to ask them to give a shit about anyone else. That’s been my big takeaway from interviewing kids and people who have broken the law. Barry [Keoghan]’s character is more representative of that: a generation hellbent on individualism. A lot of this movie is about this relentless pursuit of status and the trappings of wealth that has deeply invaded our society.

LG: This is an L.A. crime thriller through and through. How did you want to portray the city in this film?

BL: I’ve always had a love-hate relationship with L.A. I love visiting, but that status anxiety can quickly get into your bones. You can live in L.A. and glide between your beautiful home and marble office without ever touching the underbelly. The rich live literally higher, in the hills or as far west as possible. Below them lies a whole underbelly. At the start of the film, a diamond travels from downtown L.A., from an immigrant family, to Calabasas. In the 45 minutes it takes, it quadruples in value—just by virtue of moving closer to wealth. Los Angeles is a place where youth, beauty, and money come at the expense of others. Elia Kazan said that Willy Loman’s fatal flaw in Death of a Salesman is the same flaw for most living inside capitalist structures, in which he seeks his self-worth not from within but from what other people think of him. It’s easy to get sucked into that. Los Angeles is proof of that.

LG: I also noticed that the film has an interesting relationship with authority, namely the police.

BL: One of the people who I spoke to most was the consultant for [Mark] Ruffallo’s character, who was an LAPD detective who now no longer works there. He said the reason he left was because there was more pressure on delivering the numbers than his duty as a public service. All of the pressure was on delivering “targets”. I wanted that in the film.

LG: Your parents were both artists. What did they pass on to you?

BL: My mum was a successful figurative painter, then became a mime artist, then a theatre director. Growing up, I shared her with the theatre: she put everything into challenging, revolutionary productions. It was incredible work, but often-times, they wouldn’t find their audience.

I was going to art college, but I didn’t want to live in poverty like my parents and their friends. Part of wanting to make a movie of scale does relate to that thing of watching my mum pour her heart and soul into these beautifully-executed productions that not enough people saw. It’s about the challenge of doing something that might bring eyeballs to the work, but finding the way to smuggle in big ideas in the process.

“The irony is that when you speak to real thieves, the stories are so unbelievable that if you put them in a film, audiences wouldn’t buy it.”

Bart Layton

LG: Do you remember the first time you realised that movies had the power to make that kind of impact?

BL: My mum took me to see Jean de Florette (1986) when I was 10. It’s about a small town whose water gets cut off and experiences an intense drought. There’s a scene where every department at the director’s disposal worked together to create a brittle sense of drought and dryness and thirst. And that made me thirsty. I wanted water in the way that these characters wanted it. That direct line of empathy from screen to audience changed everything for me.

LG: What other movies inspired Crime 101? I saw a lot of Michael Mann in this film.

BL: Thief. Heat. Dog Day Afternoon. William Friedkin. When I made American Animals I got summoned to Friedkin’s house for lunch. I got a message saying the movie blew him away and that he would love to meet me. I went to his house, and it was everything you’d imagine from a 70s/80s Hollywood movie director house. I don’t think I had much good chat [laughs] but I wanted to ask him about the car chase in The French Connection and To Live and Die in L.A. But the answer to how he made those scenes so visceral was that it was simply another era for health and safety, and they were allowed to do crazy shit. With Crime 101 I was trying to create a bit of a feeling of that, but safely.

LG: What keeps drawing you to heist films?

BL: It’s a perfect narrative structure. You’re constantly building toward a question the audience desperately wants answered. Once you have that grip on them, it gives you room to play and push against tropes, to explore deeper themes. American Animals was different, because it’s about life imitating movies. Crime 101 is the reverse—it’s a popcorn movie with big ideas about life.