ARF: Was there a personal sense of nostalgia when shooting The Hand of God, being from Naples yourself?

DD: Shooting THoG for me was an emotional journey through memory. Paolo and I have been linked for many years, as we have very similar families in terms of social background and a joyful confusion. We began to approach working on sets more or less in the same years. Retracing fragments of memory that are very dear to me, through Fabietto’s eyes, was a gift. Naples certainly plays an important role, but more than a story about the city, it is about discovering a life-saving passion, of the delicate and complicated moment that is youth. To the places and people—I tried to give back the love, humanity and truth that I found in the script. Nothing more.

ARF: Growing up, how did Naples inspire the way you find and tell stories?

DD: Naples is a complex city, capable of great beauty and incredible pettiness. It drags you in its fast movement and then leaves you alone and lost in the infinite horizon of the sea. It gives you the greatest proof of humanity and immediately afterwards it hurts you. It continuously gives you something and continuously takes away something from you. For this and much more I think it influenced me, but it is impossible for me to articulate how much.

ARF: There is an element of the fantastical, the surreal, in the film, and indeed in many of your films. How do you build that world in collaboration with Paolo?

DD: Paolo and I work very well together. His writing is full of ideas, and he builds a world that is immediately clear. As I read, I already see unforgettable images. He knows what he wants and knows how to communicate it directly. I listen a lot and usually, since we have been working together for so many years, there is a good understanding between us. I like him a lot because he is very focused and decisive. His way of doing things pushes you to always be courageous in your choices and bold in your thoughts.

ARF: What piece of advice have you received that has been most invaluable to your work as you learned your craft, perhaps from Luca Bigazzi, who you began with? What advice would you give to people beginning their own journey?

DD: Luca taught me to be focused and to pay close attention to all the details that compose a shot. His passion, his energy and his talent are still inexhaustible sources of inspiration. I am very grateful to him for all this, and for recognizing in me abilities that I did not know I had. The advice I can give is to read a lot, be curious, travel and pay close attention to what is happening around. To bring meaning into what you do, you need to live, have experiences. To grasp and know how to exploit the advantages that opportunities for growth offer. Obviously I recommend that you put care and perseverance in everything you do.

ARF: In an era of audiences watching films on smaller screens, what is lost in your work that we usually experience on a larger cinema screen? Perhaps the details of faces or light?

DD: I believe that more than anything, the viewer misses the beauty of the immersive and collective experience that cinema gives you. Watching movies on small devices is certainly more distracting. The vision risks becoming more and more distracted and passive. I still believe that the telephone is made for making calls while cinema is made for travelling. That’s why I keep thinking about the big screen as I shoot.

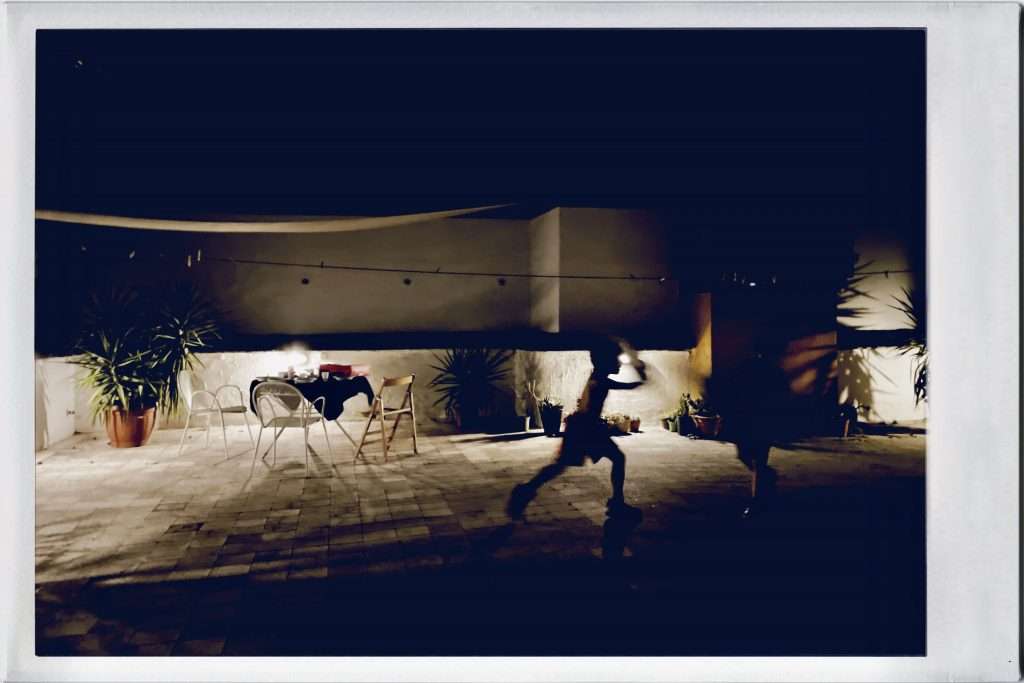

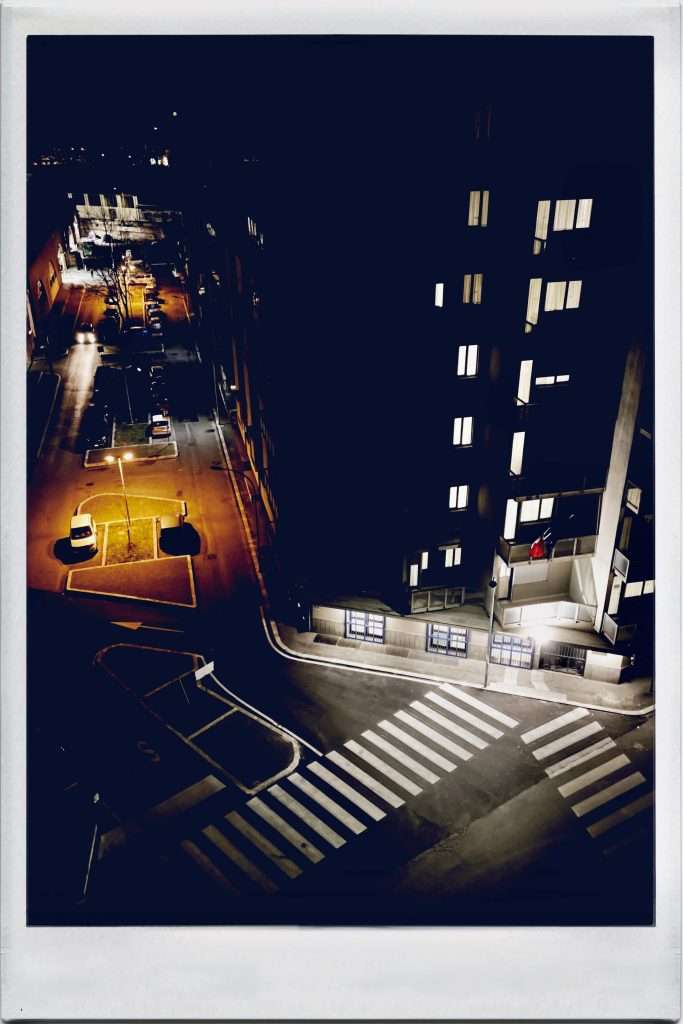

ARF: Your camera seems so present, aware of the moment—whether it is serene or chaotic. Where do you, yourself, find moments of beauty in everyday life?

DD: I always try to look at things from a different point of view. I try to apply the privilege that my work gives me in everyday life, too. Beauty is in many things, sometimes small or simple. It is necessary to know how to grasp it with patience, attention, and sensitivity. I love spending time with my family, I love travelling with them and listening to my children’s thoughts.

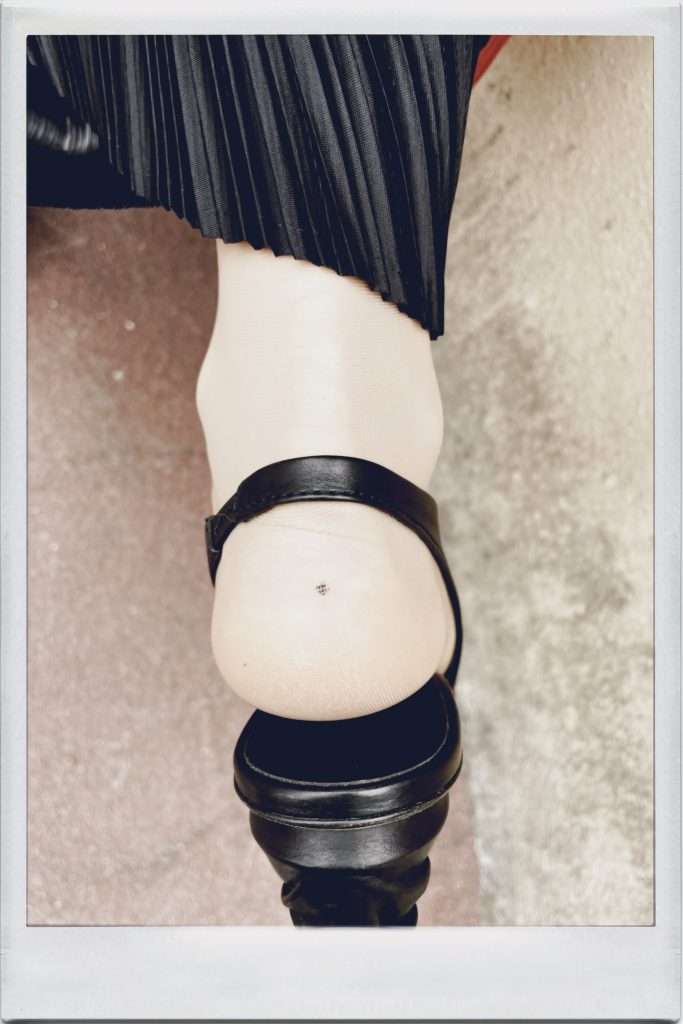

ARF: What makes an image important or special?

DD: An image is important if it is made with love, care and necessity, and it becomes special when it has the capacity of drawing out feelings in the viewer.