While I don’t like to deal in hypotheticals or go chasing truly impossible ideas, there’s a game I like to play about if I could go back in time that all I’d want to do is witness. I wouldn’t want to change anything or get a chance to speak with some long-dead relative who I’ve been told I inherited some awkward facial feature from. No, I’d do something small like go into a movie theatre in the 1960s when A Fistful of Dollars made it across the ocean to America and just watch how people react. I pick that film in particular because it’s the first of Sergio Leone’s iconic “Dollars Trilogy,” and like any other great piece of art, I am fascinated by what came after it. I love how the ideal of the Spaghetti Western would go on to become this massive influence not just on modern film, but on culture, and seeing it in its early days when people were just witnessing it for the first time is fascinating to me. But I’m honestly even more curious to know if people would laugh. Because, to me, Leone was a master of funny. Not “Ha-ha” funny, mind you. But rather the sort of dark, existential stuff that makes you chuckle a little because humanity is deeply flawed and the universe is all about chaos.

You see it right away, in A Fistful of Dollars. Clint Eastwood is the Man With No Name. He’s riding into town on his horse, a church bell is ringing, he looks up at a noose and then sees another man on a horse riding towards him. As the horse gets closer, we see a shot of the man. He’s dead. His eyes are closed, and his body has been sent on its way out of town. Somebody put a sign on his back that reads “Adios amigo.” Eastwood, as his macho, stoic character, seems very whatever about it. And for some reason, I find it hilarious.

But it’s really the absurdity I come for more than anything. I can watch Leone’s westerns over and over while I can usually only do his American contemporaries’ takes on the genre once, maybe again a decade later. Part of that, I’ve come to understand, is because American directors like John Ford, then later Howard Hawks or Sam Peckinpah, are from the country. There’s more of an understanding of how the western part of the country and America’s expansion out there showed the best the nation had to offer, but more often than not, it brought out the very worst, genocidal, greedy, tendencies of the United States. In Leone’s take on the west—or, to be more exact, Mexico, where the trilogy is always set—America’s stigma doesn’t follow the film around. It’s more about man vs. man in an unforgiving place. Nobody is really “good” or “bad,” but we have an anti-hero in Eastwood’s character that we can’t help rooting for because he’s so cool, calm, quiet and smarter than all his adversaries.

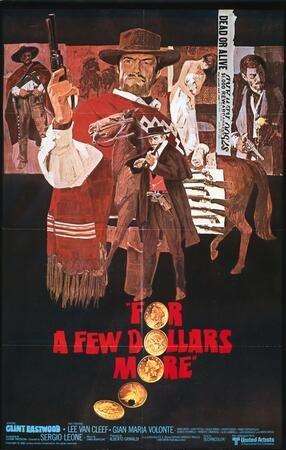

He’s also maybe superhuman. Which makes the whole thing even sillier. One scene, in A Few Dollars More, Eastwood’s Man With No Name swaggers into a saloon. He walks over to the table where the man he’s looking for is playing cards, inserts himself into the game and just wins—not because he’s a good poker player, but that’s just what he does. It’s like he could see the future and it told him the hand the other guys had and he was confident of victory. And what was the point? There was none. It was just so Eastwood could then start beating the hell out of the other guy. The whole scene is wedged between badass and silly but doesn’t quite go totally to the latter because it’s Eastwood and nobody did things the way he did it before he did. Anybody that did anything like that before the Dollars movies would look silly.

And that’s often—not always—what has worked after Leone and Eastwood. When there’s humour in a western, whether it’s pure slapstick like in Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles, or it’s unsettling and existential like Jim Jarmusch’s 1995 film Dead Man, I like to think it’s a little homage to the Italian director whose films still deserve re-watching and unpacking all these years later.