Newly arrived in Rome, international movie star Sylvia—played by Anita Ekberg—faces the usual questions from the press. “Do you believe Italian neo-realism is alive or dead?” someone asks—and one of Sylvia’s entourage whispers to her, “Say yes.” ‘Yes’ is clearly the right answer, for 15 years after Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City and 12 years after Vittorio De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves, Federico Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960) proved that the movement that reinvented Italian cinema was still very much alive.

This might seem counter-intuitive: we tend to think of Fellini’s cinema as an unruly, sprawling circus of fantasy, autobiography and surrealistic excess, surely a world away from realism. Yet, three years before the director soared into the imaginative stratosphere with his 8 ½, Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, even in its wildest visions, was still very much rooted in the real, and in the recent headline history of Rome. The episode in which photographers flock to the scene of a supposed sighting of the Virgin Mary was inspired by a real press flurry over a similar episode in 1958. The wild night that is the film’s climax was inspired by a party at the restaurant Rugantino, where a Lebanese dancer called Aiche Nana became famous overnight for a spontaneous striptease. Then there’s what might seem the most outré Fellini touch, when Sylvia visits St Peter’s in an outfit modelled on a priest’s soutane and biretta: even this comes from reality, closely echoing the ecclesiastical styles created in 1956 by fashion designers the Fontana sisters.

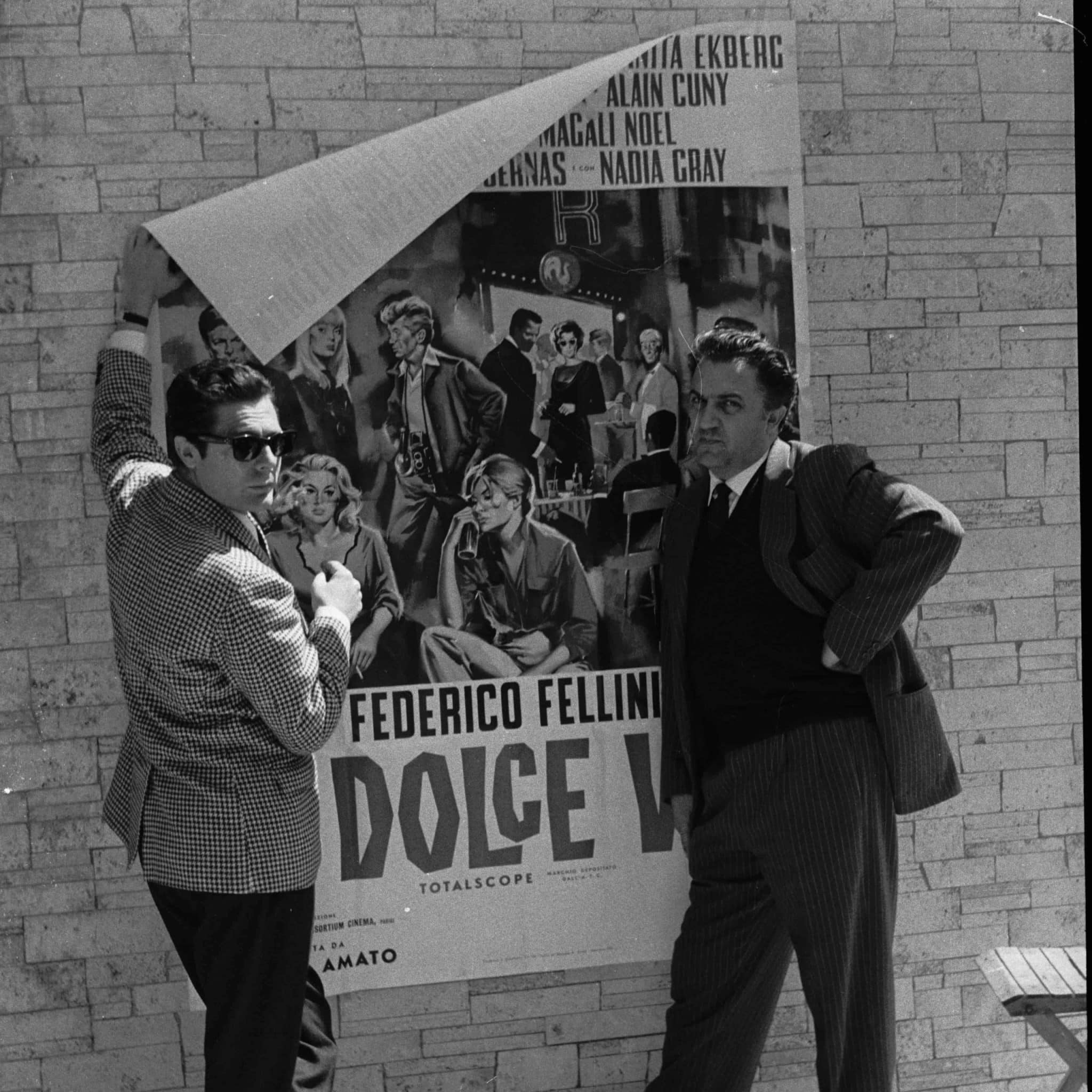

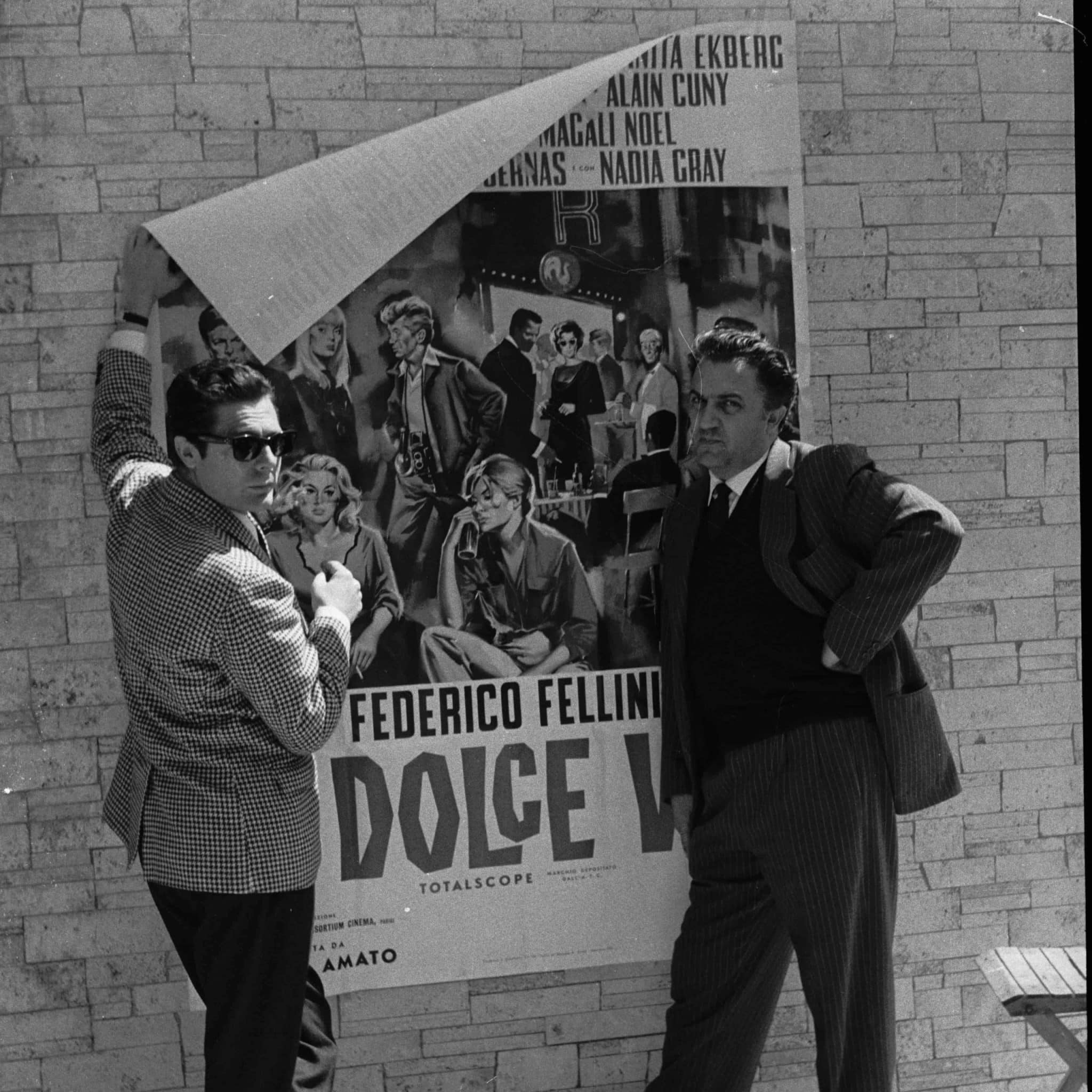

Aspects of La Dolce Vita’s Rome are real: some of the film was shot on location in the city and its outskirts. But many of the settings were recreated at the Cinecittà studio—including the dome of St Peter’s and even Via Veneto itself. This street was the centre of the glamorous social scene that was the feeding ground for gossip journalists like the film’s anti-hero Marcello (Marcello Mastroianni) and the hordes of photographers always ready to pounce on a hot story, or create one from the slightest incident. Famously, one character, Marcello’s photographer sidekick, overnight gave his name to the trade as it still thrives today. Borrowed from a book by George Gissing, the name ‘Paparazzo’ suggested to Fellini a buzzing, insistent insect, and in La Dolce Vita, the paparazzi indeed swarm pestilential—never more callously than when mobbing a woman who doesn’t yet know that she has just lost her family.

Fellini’s episodic, picaresque drama traces a fall: Marcello is first seen in the skies above the city, in a helicopter chasing a statue of Jesus that is being flown to the Vatican; then he passes through the strata of the city’s nightlife, finally coming aground on a beach, all traces of his dreams and his higher ambitions ruined. Marcello, we learn, considers himself a writer, but has become a hack—working, he’s reminded, for “a semi-fascist newspaper”. Finally, all illusions shattered, he becomes something even more base—a publicist.

La Dolce Vita has a mythical prestige: it’s often remembered as a fairy tale of impeccable glamour and chic outrage, a festival of gorgeous hedonism, embodied by Anita Ekberg’s luxurious, ecstatic wade into the Trevi Fountain at night. That aspect of the film partly accounts for its international success: La Dolce Vita was hugely successful in the US, grossing $10m. But watched closely, the film tells another story. It is an epic of squalor and degradation. Early on, Marcello and his sometime lover, bored socialite Maddalena (Anouk Aimée) spend the night at a prostitute’s flooded apartment, taking over her bed—the ultimate in bourgeois sex tourism. The party life turns all-out apocalyptic in the climactic soirée, where Marcello humiliates a hapless female guest, strewing her body with feathers, until at last she wearily protests, “It was a lovely party, but enough is enough. Basta, basta, basta…”

The film was widely denounced as scandalous, condemned by the Vatican, long banned outright in Spain and Portugal. But it is an eminently moral work—even moralistic, in its conclusion that hedonism can only end in the cold desolation of daylight. In the final scene, Marcello’s party crowd winds up on a beach in the morning, gazing at a monstrous rotting fish hauled out of the sea—the mirror image, seemingly, of their own moral condition. Fellini said of the film, “I intended it as a report on Sodom and Gomorrah”—and any evocation of those swinging cities might risk coming across as titillating tourism. But the film is also a broader attempt to diagnose the modern social malaise. Contrasted to the gadfly Marcello is the hyper-refined Steiner (Alain Cuny), a man who loves his family, who can casually knock out Bach’s Toccata on a church organ, and who reads Sanskrit grammars for pleasure. Yet Steiner’s deep-lying apprehension of the abyss culminates in a truly horrifying act of despair.

New York Times critic Bosley Crowther called the film “a withering commentary on the tragedy of the over-civilised”. It’s also a withering commentary on aspects of modernity that have become increasingly familiar since the early 60s. Fellini and his co-writers—Ennio Flaiano, Tullio Pinelli, Brunello Rondi—conceived the film partly as a critique of the new unreality that showbiz and its parasite industries had introduced into the twentieth century. The director commented, “Today is the day of the journalist, the cameraman, mechanisation and of café society”— in other words, what French Situationist thinker Guy Debord would call the Society of the Spectacle.

La Dolce Vita was hardly the first modern film about the ways in which the media was reshaping our experience of the world: in 1957, Alexander Mackendrick’s Sweet Smell of Success and Elia Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd had similarly examined a world fuelled by the hollow agitation of hype. But La Dolce Vita analysed the craziness in its European manifestation, and brought the real fauna of Rome’s social jungle to the screen. Fellini’s cast includes real-life habitues of the Roman scene, including artists, aristocrats, journalists and socialites, including gay scenester Giò Stajano (later the Contessa Maria Gioacchina Stajano Starace Briganti di Panico). In a self-reflexive touch, the celebrities were played as celebrities by celebrities. The manic rocker who entertains Sylvia in an early scene is real-life star Adriano Celentano. Sylvia is manifestly at once Sylvia and Anita Ekberg, while her drunken actor date is played by Lex Barker, a one-time screen Tarzan; their sour moments on the Via Veneto recall Ekberg’s own much photographed arguments there with actor husband Anthony Steel.

Most famously—although in 1960 she was just part of the crowd—Christa Päffgen, a German model known as ‘Nico’, plays Nico, a model engaged to a scion of the Italian aristocracy. She whisks Marcello off to a party at a castle, where assorted nobles and their retinue go on a ghost hunt; it’s the film’s most beautiful, eerie sequence, as they troop through the gardens of the Giustiniani Odescalchi Palace at night. They don’t realise that they are the ghosts, Italy’s etiolated living dead (in 1960, they would inescapably have been seen as remnants of the Mussolini era). Nico, seen jovially goofing around, would a few years later become legendary in her own right: as a transcendentally melancholic singer with The Velvet Underground and a regular at Andy Warhol’s Factory, she would come to embody a social scene more hedonistic, lawless, socially and artistically radical than anything Fellini could have imagined. Her 1967 rendition of The Velvet Underground’s ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’ is all the more soul-wrenching because Nico was intimately acquainted with yesterday’s European parties, where the ingénue ‘poor girl’ of Reed’s song might well have protested, “Basta, basta, basta…”

La Dolce Vita won the Palme d’Or in Cannes in 1960, beating another instantly controversial Italian masterpiece, Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’Avventura (the following year, Antonioni would make his own party-centred drama La Notte, also starring Mastroianni, although its festivities were infinitely more austere). La Dolce Vita has left its mark in history, not least in popularising its title phrase (rarely used with the irony Fellini gave it). It has been alluded to or excerpted in other films, among them Cinema Paradiso and Lost In Translation.

Most substantially, La Dolce Vita was paid extended homage in Paolo Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty (La Grande Bellezza, 2013), a new hymn to Rome. Its protagonist Jep is a jaded littérateur turned star journalist, alla Truman Capote: Marcello, as if he had achieved greatness, but idly cast it away. Seen by some as a 21st-century update or remake of Fellini’s film, The Great Beauty is really a transformation of a still essentially realist work by Fellini into something different: a modern celebration of the full-blown Felliniesque, using grotesque, fanciful images that take their cue from the director’s later, more oneiric work. Sorrentino contemplates something that the pessimism of La Dolce Vita tends to obscure: the sublime, the spiritual, the possibility of a beauty that is not diminished by modern city life but that, despite everything, is intrinsically, irreducibly, magically part of it.