Whether it’s tarot or lunar cycles, in 2024, it seems as if basically every woman I know is curious about the supernatural and the mystical. And recently, our zeitgeist has been turning towards the figure of the witch, her popularity levitating alongside a belief in her redemption.

Just look at the popularity of Marvel’s Agatha All Along, a show about a spellbound witch, Agatha Harkness (Kathryn Hahn) and her journey to regain her powers. Even one of its stars, Aubrey Plaza, hails the word “witch” as the new “brat”. Or the anticipation for Wicked, the live action adaptation of the broadway hit, and a sympathetic retelling of the wicked witch of the west in The Wizard of Oz, set to release in cinemas next month. Also released this year is Witches, Elizabeth Sankey’s intimate documentary exploring the relationship between postpartum depression and the portrayal of witches in popular culture. Mixing personal testimonials with historical film footage, the documentary analyses our cultural views on witches in a larger sociological context, looking at the ever changing depiction of these magical characters on screen and how they continue to haunt our cultural perception of womanhood.

In the late 19th century, the perception of witchcraft was far from what it is today, American writer and suffragette Matilda Joslyn Gage argued that the persecution of witches was not a fight against evil but a misogynistic resistance to the intelligent women. A revolutionary idea at the time, Gage insisted that witches were simply women of intellect, so feared by the patriarchy: “as knowledge has ever been power, the church feared its use in women’s hands, and leveled its deadliest blows at her.” Ironically, she is said to have influenced her son-in-law L. Frank Baum, on his most famous novel, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, who’s original film adaptation provided its audience with the caricature of the evil witch, with her green skin, pointy nose, flying broomstick and black hat.

Looking at the portrayal of witches over the last century, it becomes obvious how their depiction in popular culture appears as a direct reaction to changing social and political attitudes towards gender and the rights of women. As an archetype they represent not only our culture’s subconscious anxieties with powerful women but also the progressive political response towards this. Although originally popularised on screen in the 1930s as evil hags, due to the continuation of feminist movements, the depiction of witches has transitioned from a vengeful crone, to a seductive woman, teenage girl and now a redeemed feminist.

When I watch early depictions of witches on screen such as The Wizard of Oz (1939) or Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) these characters appear as an almost foreign concept, far removed from the contemporary idea of the magical woman. These cartoonishly evil women are shown as old hags placed in direct contrast to the young beautiful innocent protagonists who we as an audience are supposed to root for and sympathise with. Although they appear to have incredible magical power much of their motivation appears to be rooted in bitterness and jealousy, mirroring society’s perception of the powerful older woman, whilst the relevance of Gage’s words echoes through our contemporary collective consciousness.

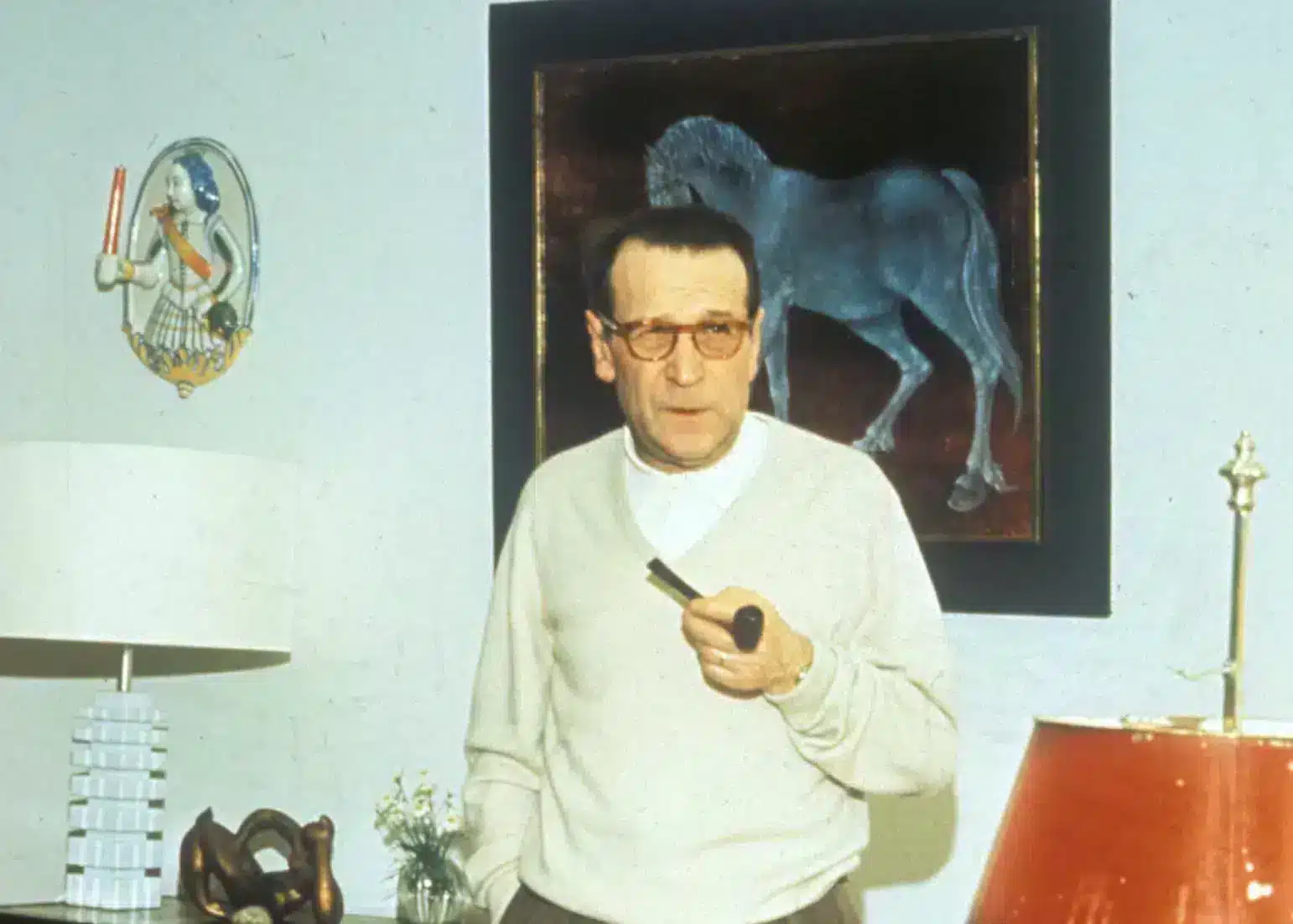

The 1940s and 50s saw little evolution in the depiction of witches on screen, as Hollywood still relied on the troupe of the evil woman only without the green skin and pointy hats. Films such as I Married a Witch (1942) about a witch (Veronica Lake) taking the appearance of a normal human to act a femme fatale; and Bell, Book and Candle (1958) which follows Gillian (Kim Novak), a witch who casts a spell on a man to her make him fall in love, depicts witchcraft as tool of seduction for manipulative women. Whilst the character of Maleficent in Sleeping Beauty(1959), continued the Disney’s legacy of portraying witches as wicked villains who seek the demise of the story’s innocent protagonist.

However, the 1960s saw a shift in popular culture’s reaction to the character of the witch, with the arrival of Bewitched, a TV show about the nose-twitching suburban Samantha Stevens (Elizabeth Montgomery). In an era of second wave feminism, as well as cults and the rise of Wicca, a form of modern paganism linked to witchcraft, Bewitched felt like a reaction to the changing culture, making these magical characters more palatable for the remaining conservative audience. While the show echoed in an age where witches were shown less as vengeful creatures but as beautiful women with more similarities to magicless counterparts, the desires ofBewitched’s protagonist were far removed from feminists at the time. Although created during the hippie movement and free love, Samantha who possessed almost unlimited power desired nothing more than to be a normal housewife, an idea in direct contrast to second wave feminists who fought for substantive equality and the rejection of forced domesticity.

With the removal of the Hays Code, a strict industry guideline for censorship, in 1968, the archetype of the witch saw significant new freedom during the 1970s. During this period, the character of the witch became more complex, who could either be a symbol of female rebellion or one of terror, and with the continuation of second wave feminism many of these films explored societal anxieties around the changing conversations around gender. This includes the cult horror Season of the Witch in 1973, which follows a bored housewife Joan (Jan White), who becomes involved in witchcraft to escape her mundane life. Influenced by the feminist movements, director George A. Romero, sought to create a film that sympathises with the witch character, portraying witchcraft less as an evil practise by a source of freedom against suburban domesticity, framed as the ultimate nightmare, a far cry away from the previous decade’s Samantha Stevens and her desire to be the perfect housewife.

Another significant supernatural film during this era was the Italian horror, Suspiria (1977). Directed by Dario Argento, the films revolved around American ballet student Susie Bannion (Jessica Harper) who travels to West Germany to attend a prestigious dance school but after a series of murders discovers it is run by a coven of witches. With an incredibly female centric-cast, the witches in this film are shown as menacing creatures, rather than green skinned bitter women on a broomstick. Plus, whilst the few male characters are depicted as helpless or creepy, not only are the witches in Suspiria portrayed powerful beings, the film’s protagonist Suzi, also transforms from being a vulnerable and naive student to a capable woman.

Due to growing conservatism there was a significant lack of films with a focus on the witches in the 1980s. With the rise of Satanic Panic, where 12,000 unsubstantiated cases of Satanic ritual abuse were made in the United States, there was widespread fear around witchcraft, leading several films containing such characters to be delayed. And the only films which were accepted had to appeal to a wider audience by leaning into a comic genre. The most famous of these was George Miller’s The Witches of Eastwick (1987), which follows three friends (Cher, Michelle Pfeiffer, Susan Sarandon) who, unaware that they are witches, form a happily unconventional coven… until the mysterious Daryl Van Horne (Jack Nicholson) comes to town. Unlike films from the previous decade, which carried strong political and social commentary, the gender politics in the film is muddled. Some hail it as a female empowerment movie whilst others view it as a story about magical women which places women in traditional gender roles. Although a film centred around three women, much of the film focuses on Nicholson’s character, as are the women framed as objects of desire.

The 1990s saw a dramatic change in the depictions of witches as many of these portrayals spoke to the growing third wave feminist movement. In the start of the decade, The Witches (1990), a story about bloodthirsty witches who disguised as ordinary women try to rid the world of children by turning them into mice, terrified a generation of young kids. Based on the Roald Dahl novel of the same name, the book was controversially slated by second wave feminists of the 1980’s, including critic Catherine Itzin who claimed that the book is “how boys learn to become men who hate women.” Playing on similar tropes used in cartoon fairy tales, of the evil haggard woman, the portrayal of these witches is a far cry away from the characters which became popular in the coming years.

As the third wave feminist movement grew and the conversation around gender inequality became more widely discussed, the media’s depiction of these powerful women shifted. By the mid 1990s the witch became synonymous with teenage girls, as a string of adaptations about magical women were set in high school. Long were the days where witches were old and bitter, vengeful against the youthful chosen enemies, by the end of the twentieth century these characters were reclaimed as angsty adolescence, with enviable style and cool friends. On the small screen, the title character in Sabrina the Teenage Witch (1996-2003) and lesbian witch Willow in Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) were both lovable girls, whom despite their powers still had to tackle the trials and tribulations of being a teenager, making them feel familiar to an audience who watched them weekly.

During this time films including the cult horror The Craft (1996) and Practical Magic (1998) explored the concept of witchcraft and the coven as a form of female solidarity and overcoming the patriarchy. The Craft, a dark look at young womanhood, follows a group of four girls, who were treated as outsiders, but once discovering their magical abilities use these skills to overcome their unfortunate situations and tormentors, before eventually submitting to their power-hungry desires. Grappling with the issues which continue to face young women, from sexual assault to bullying and unrealistic beauty standards, The Craft, delves into the topics concerning third wave feminists, using the witchcraft as a narrative tool to further bring these issues into the mainstream discourse.

On the other hand, Practical Magic, a film about two witch sisters who possess a family curse where any man they love will meet an untimely death, explores the topic of sisterhood and a celebration of matriarchy. Although an overall lighter viewing experience, told with the tone of a romantic comedy, Practical Magic, like The Craft, tackles issues including domestic violence with an extremely contemporary lens, as witchcraft is explored as a feminist tool against female oppression.

In the 2010’s the portrayal of witches on screen shifted dramatically. Many of the films with mystical female characters were period pieces, focusing on the historical persecution of witches and the reflection on contemporary culture, from the chilling folk horror The Witch directed by Robert Eggers in 2015 to (2016).

Set in pilgrim New England during the 17th Century, The Witch follows a family banished from settlement society who are haunted by a sinister witch, yet wrongly blame the teenage daughter Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy) for their misfortune. Focusing on the misogyny within a puritanical Christian culture, the film is a mirror to the values of early America and its legacy today. As the story continues, witchcraft in revealed as an ultimate tool of rebellion against the patriarchy, as Thomasin who eventually gains freedom from a society who persecutes her, only receives this power once she accepts salvation from Satan and embraces the coven.

Released the following year, The Love Witch explores the concept of the witch as a seductive character and a product of the male gaze. Although not set in any specific decade, the film not only borrows from the aesthetics of the 1960s horror and technicolour, but also examines attitudes of the time. Like Samantha Stevens in Bewitched, the film’s protagonist Elaine (Samantha Robinson) wants nothing more than to be loved by a man, a desire which frequently backfires leading to the demise of many of the men she meets. While both films explore the relationship between the oppression of women and the persecution of witches, they comment not just on the historic fear of witchcraft, but these characters’ continued representation as vessels of freedom against the patriarchy.

Now that our captivation with the witch is as strong as ever, it’s inevitable that we’ll continue to be introduced to new renditions of this magical archetype. However, with ever changing conversations around gender it’s clear that over the next few decades the representation of witches on screen will persistently evolve, as we see where cinema will take her next.

Main image: The Love Witch (dir. Anna Biller).