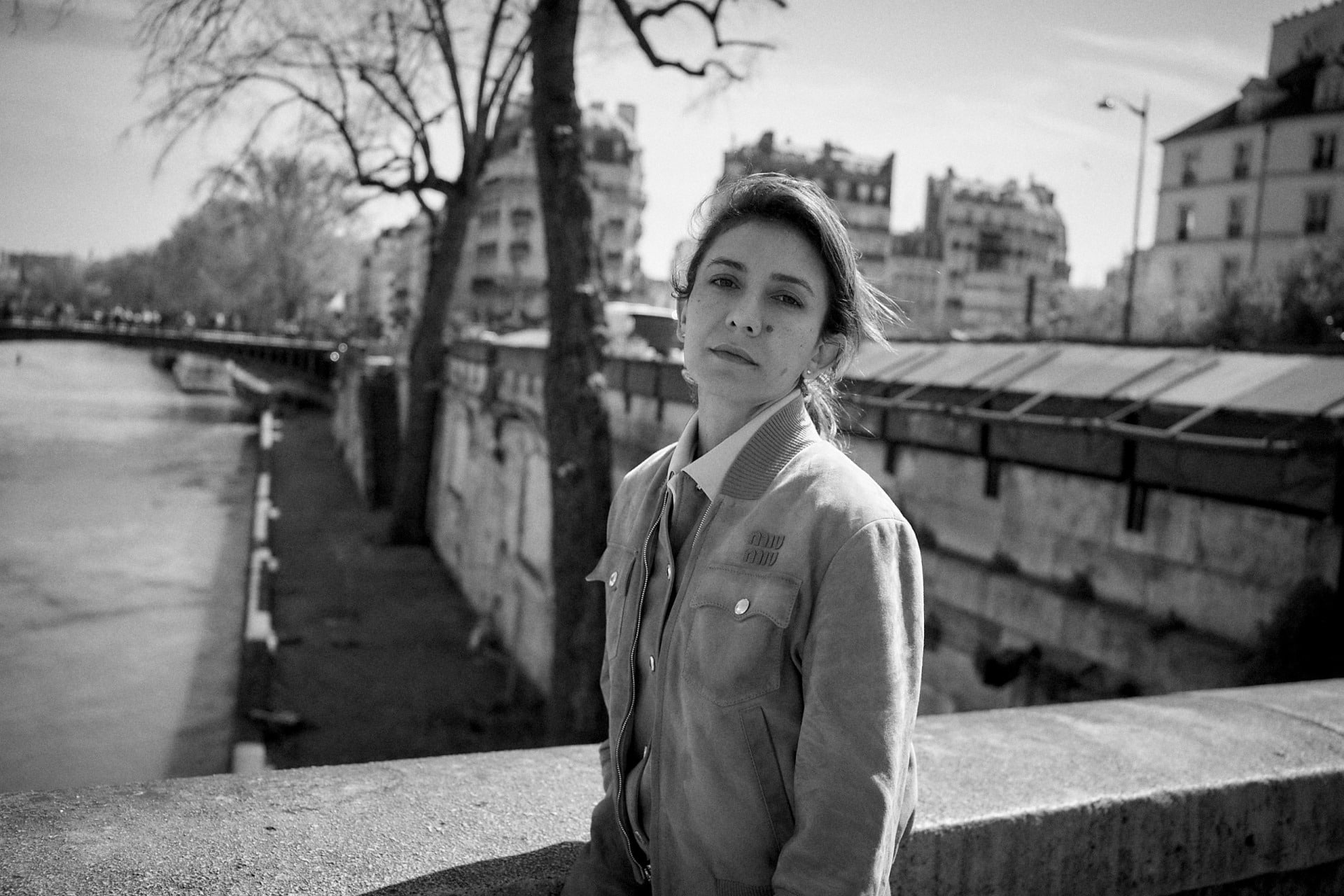

During London Frieze week, Lucca Hue-Williams, the founder and director of Albion Jeune, sits down with Los Angeles-based artist Su Yu-Xin to discuss her latest exhibition at the gallery, Precious. Her first solo exhibition in the U.K., Precious consists of a series of dynamic paintings that examine the history of migration and the vicissitude of pigments through a geological perspective. Portraying sea caves, shells and natural objects found along the California coastline, this new body of work invites us to consider the value attribution of material objects.

Lucca Hue-Williams: Your practice of collecting materials and creating your own pigments is fascinating. Can you tell us how this began and why you choose to make your own pigments?

Su Yu-Xin: As a painter, my practice is two-fold: making the painting itself and crafting the pigments I use to paint. I went on extensive field trips, mostly in nature, where I collect materials such as soil, rocks, minerals, shells, and others.

Once I bring these substances back to the studio, I use various chemical and physical processes to extract color from them. The process is meticulous and slow, but through it, I built my vocabulary of colors.

Currently, I have around 200 pigments in my studio ready for use. Things come and go. What’s fascinating is that, unlike in stores where the most vibrant pigments are often considered the more valuable, in my studio, the pigments have its own economy. The ones I value most are the ones collected from the most challenging locations, or even pigments from places that don’t exist anymore. These field trips, all around the pacific ocean, often to wild places, provide not only the materials but also the subject-matters for my work. They create a loop where they shape each other.

LHW: You often incorporate materials with rich histories into you art. Is there one that captivates you the most, and why? Could you share a story about a material that particularly intrigues you?

SYX: It changes from day to day. In this current show, many of the shadows in my paintings are tinted with black tourmaline, a mineral I hand-mined from a historic site in San Diego. This mine was once owned by a gemologist who worked for Tiffany & Co. during the mid to late 19th century. Through the company, they sold high-quality watermelon tourmaline to the Empress Dowager Cixi of China. Many pieces from her collection, now housed in the Palace Museum in Beijing, originate from this very mine.

This gem, unearthed from the ground, became a witness to the rise of new forms of international commerce and the fall of imperial China.

LHW: As an artist, what message or feeling do you hope to convey to your audience through your work?

SYX: I want my work to convey something about the world that can’t be described.

LHW: Your uniquely shaped canvases have been described as portals. Could you elaborate on this concept?

SYX: When I sketch and draw outdoors, my drawings are often edgeless—they grow organically across the page as my gaze moves around, taking in the environment. Once I bring these sketches back to the studio, I decide what shape the canvas, or “vessel,” should take, depending on the scene I’ve captured. Is the sky expansive and rounded? Is the land shrinking or stretching? Through this shaped sights we look into the landscape on the other side.

LHW: Recently, you’ve begun incorporating cowrie shells into your landscapes. What drew you to these shells, and what do they represent in your work?

SYX: I’m drawn to the history of cowrie shells and the narrative they convey on value attribution. Cowrie shells are one of the oldest known forms of currency, first recorded around 1600 BCE in ancient China and India. Originally from the Maldives, they were prized for their uniformity in size and weight when fully grown, as well as their durability, lightness, and natural beauty. These shells were transported along trade routes to China and India, and while they were never official currency in China, they were widely used for everyday transactions.

Interestingly, cowrie shells as currency were most commonly used in China’s central plains. This highlights how distance and geography play a significant role in determining value. If something is abundant on a beach, it’s challenging to assign high value to it. These various factors—geography, collection, and available technology to move them. They combine to form a value system. This applied to shells, to other collectables found during the colonial era, also the minerals and gem that I collect to create other colors in my paintings.

LHW: Your latest exhibition features both large-scale landscapes of the California coast and more intimate works you describe as colour swatches. How do these pieces interact and converse with each other?

SYX: While the smaller, book-sized works cover a vast surface of the Pacific Basin, I intentionally depict local places in California for the larger pieces. I like the tension between the scales and their content. The smaller works expansive, representing the wide-reaching geography of the Pacific, while the large-scale pieces are grounded and local.

LHW: Many artists draw inspiration from specific landscapes. Which ones have had the most profound impact on your work?

SYX: I have to say the East Coast of Taiwan has had the most impact on my work. It’s the landscape that raised me.

LHW: Can you give us a glimpse into your current or upcoming projects? What new directions are you exploring in your practice?

SYX: I’m going on to a field trip next month to south of Japan to look into the geothermal activity and the natural hot spring spots there.

And then I have museum solo show in California opening in January. The show will sample different air phenomenons, real or fictional, all around the pacific ocean.