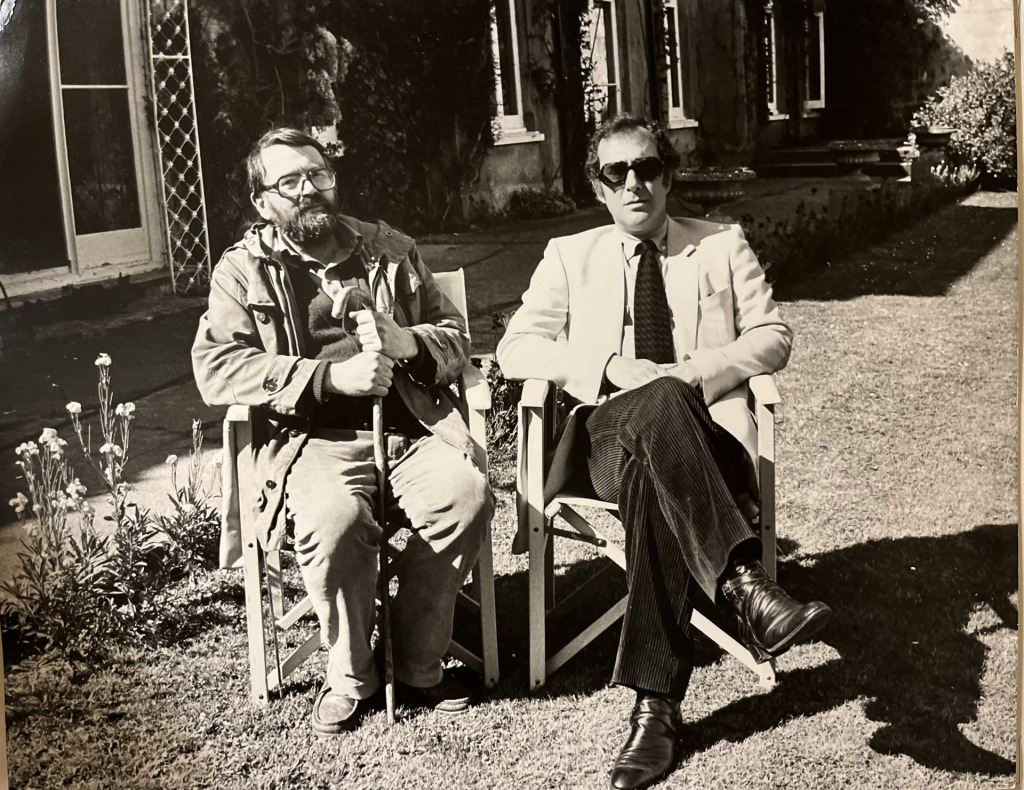

This Sunday, I’ll be discussing Michael Anderson’s The Quiller Memorandum (1966) with Michael Billington as part of the ‘Pinter on Screen’ series at Chiswick Cinema. Based on Adam Hall’s best selling spy novel, the screenplay was by Harold Pinter, my stepfather. Written after Joseph Losey’s The Servant (1963) and Jack Clayton’s The Pumpkin Eater (1964), Quiller was unusual for several reasons, it was the first and last time that Harold adapted a spy thriller—“I was never asked again,” he told me; Harold wasn’t invited on set—usually film directors welcomed him—and Adam Hall resented Harold’s decision to change Quiller—his English hero—into an American. With hindsight, it was wise. Who could compete with the very British and charismatic Michael Caine (Harry Palmer) or Sean Connery (James Bond)? Besides, George Segal (Quiller) proved to be excellent.

Harold Pinter blew into my life when I was eleven. He had run off with my mother, the writer Antonia Fraser. Albeit renowned for being ‘the master of menace,’ I had never met anyone who was so straightforward and respectful to kids. It was 1975 and Harold had just written The Last Tycoon screenplay, based on F. Scott Fitzgerald’s unfinished novel. Produced by Sam Spiegel, directed by Elia Kazan, the film starred Robert de Niro and featured Jack Nicholson, Tony Curtis, Jeanne Moreau, Donald Pleasence and Robert Mitchum. The highly anticipated movie flopped, but Harold bonded with de Niro.

The friendship does not surprise because my future stepfather treasured actors, appreciated their vulnerability and enjoyed their company. To such a point that the term luvvie sent Harold into a Thor-like rage. To his mind, it was insulting to “a courageous and passionate group of people.” He felt that protective. I am often asked why so many of Harold’s screenplays got made—there were fourteen including Accident (1967), The Go-Between (1971) The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1981), Betrayal (1983), Reunion (1989), The Handmaid’s Tale (1990), The Comfort of Strangers (1990) and Sleuth (2007). To my mind, several factors were afoot. Understanding actors obviously helped, as did relishing film and the company of directors. Harold believed in the importance of performance achieved in film—he was influenced by the actors of his youth like Robert Newton—and he was moved by films such as Napoléon, Abel Gance’s silent classic. With regard to his writing process which meant writing on long yellow legal pads, Harold spoke every line out loud. The words had to sound right. Having been trained as an actor, it made sense.

Prior to meeting Harold, I had seen all his Losey films such as The Servant, Accident and The Go-Between as well as Clayton’s The Pumpkin Eater. However, through him, I was introduced to the Marx Brothers, greats like Charles Laughton, Anton Walbrook, Raimu and all the early films of Carol Reed that were screened in the ground floor of his office. In Harold’s play, Old Times, Reed’s Odd Man Out is referenced whereas Harold later admitted to Michael Billington that his first play, The Birthday Party was influenced by The Killers (1946) Robert Siodmak’s film noir. Harold’s passion for film was infectious. I can still remember his excitement when BBC2 showed Thorold Dickinson’s The Queen of Spades (1949) with Edith Evans – “it is a masterpiece,” he said or watching Henri-Georges Clouzot’s La Salaire de la Peur and Gillo Pontecorvo’s La Bataille d’Algiers. Then there were his discoveries such as Steven Spielberg’s The Duel and his howls of laughter when watching Rob Reiner’s Spinal Tap and Paul Bartel’s Eating Raoul.

Harold believed in the importance of performance achieved in film—he was influenced by the actors of his youth like Robert Newton—and he was moved by films such as Napoléon, Abel Gance’s silent classic. With regard to his writing process which meant writing on long yellow legal pads, Harold spoke every line out loud. The words had to sound right. Having been trained as an actor, it made sense.

Natasha A. Fraser

On three occasions, Harold tried working with the director Mike Nichols. The projects were The Last Tycoon, Betrayal and The Remains of the Day, Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel that Harold had personally optioned. Exhilarating as the experiences were, there weren’t hard feelings when Nichols left for bigger Hollywood projects. “Mike’s lasting fear is financial failure,” Harold told me. “His attitude is puzzling but then I’m not part of the Hollywood system.”

Early in his career, Hollywood came knocking. Kirk Douglas invited him to his home. It led to uncredited work on The Heroes of Telemark (1965.) Standing by his pool, the diminutive film star was wearing swimming trunks. “I remember how he put out his hand and then proceeded to crush mine,” said Harold. There was also his first experience with Sam Spiegel who had optioned Accident. “What is this script?” asked the film mogul. “It’s all muscle and no flesh.” And then there was Harold’s letter to the Academy of Motion Pictures and Arts. Since two of his screenplays were nominated for Oscars (The French Lieutenant’s Woman and Betrayal), he became a member of the Academy. Somewhat neurotic, Harold could not deal with the constant boxes of films he was sent—the mess of cardboard and sellotape. As a result, he wrote to the Academy asking that they desist. (This must have been a first.) There was an uprising from myself and other stepchildren. Gently persuaded by my mother, another letter was sent to the Academy, reversing his decision. Fortunately, the Oscar films returned.

Pinter on Screen, held at the Chiswick Cinema in London, runs until September 2024. It’s being curated by Michael Billington, Harold Pinter’s official biographer, in collaboration with the Chiswick Book Festival’s Torin Douglas and Chris Parker. chiswickcinema.co.uk

Natasha A. Fraser is the author of Harold! Ma Jeunesse avec Harold Pinter (Grasset 2023).