America: the mid to late 1980s. We’re deep into Nancy Reagan’s Just Say No campaign, and the American government’s war against drugs has seen the rise of mass incarceration of marginalised communities at an unprecedented level. Meanwhile, Gus Van Sant, an up-and-coming director in his early thirties, is preparing to shoot his game-changing second feature Drugstore Cowboy (1989). His premise? A gang of heroin addicts in Portland get their fix by robbing drug stores.

Van Sant was hot, having just released his DIY filmmaking indie masterpiece Mala Noche in 1986, which he wrote, produced, edited and directed with a micro-budget of $25,000. It was the breath of fresh air that the American film industry didn’t know it needed. Adapted from the story of the same name by Walt Curtis, the film told of a 30 year old queer American man who becomes infatuated with a 16 year-old Mexican migrant. “I had no idea if it was going to be watchable or even artistically whether it would capture people’s imagination,” Gus Van Sant tells me. “But I worked really hard on it.” As we speak over Zoom, the director leans back in his desk chair at a 120 degree angle (there’s a reason they call him the mellowest man in Hollywood), clasping his hands in reflection.

Mala Noche was something new and exhilarating, a relief from the big box office blockbusters that audiences had grown addicted to. It shone a cinematic lens on subcultures and minorities that weren’t commonly represented at the time, and it did so with a radical sensibility. It was gritty, grainy and unpolished—and it looked all the better for it. “We were told that there was no audience for black stories, queer stories, female stories, foreign language, and no audience for anything non-white,” explains Laurie Parker, production executive of Drugstore Cowboy. “There was one kind of thing you could make. Mala Noche was a sign that a transgressive new wave was on the horizon.”

But the best was yet to come, and in retrospect Mala Noche served as an exciting prelude to a new wave of American independent cinema pioneered by young and bold filmmakers like Van Sant, Steven Soderbergh (who would release his classic Sex, Lies and Videotape the same year as Drugstore Cowboy) and Todd Haynes.

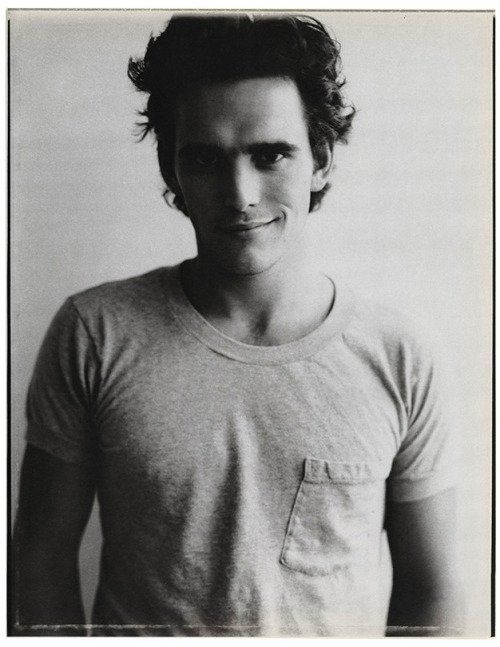

In the meantime, all eyes were on Van Sant. Avenue Entertainment had taken a chance on his screenplay for Drugstore Cowboy, which notably refused to take any moral stance on drug use, a controversial angle considering the era. “You had never seen people putting needles into their veins and experiencing that rush before,” says Matt Dillon, who plays Bob, the leader of the titular Drugstore Cowboys. “That’s one of the best things about cinema—it can reward risk-taking. And Drugstore Cowboy was one of those films that dared to risk it all.”

THE ORIGINAL DRUGSTORE COWBOY

The first seeds of Drugstore Cowboy were planted when screenwriter Dan Yost (credited as cowriter of the film) handed Gus a few manuscripts by James Fogle, a prisoner of Walla Walla State Penitentiary and one of the original real-life Drugstore Cowboys. During his sentence Fogle penned fictionalised stories about his life, two of which ended up in front of Van Sant: one was Drugstore Cowboy, and the other was a novel called Satan’s Sandbox. “Drugstore Cowboy is his life out of prison, and then he wrote this other one, which was his life in prison, which was also very good. It was actually my favourite one of those two projects.” Van Sant liked the idea of Satan’s Sandbox so much that he wrote a rough draft of a screenplay that he pitched to studios alongside Drugstore Cowboy. It’s an interesting thought: that in an alternate timeline there’s a screenplay for an unmade film called Drugstore Cowboy tucked away in a drawer somewhere. Would Satan’s Sandbox have made the same splash had it been developed as Van Sant’s breakout feature? We’ll never know, though the director admits that he still blows the dust off the screenplay every now and again. “Maybe one day I’ll make it. Things just keep getting in the way,” he says.

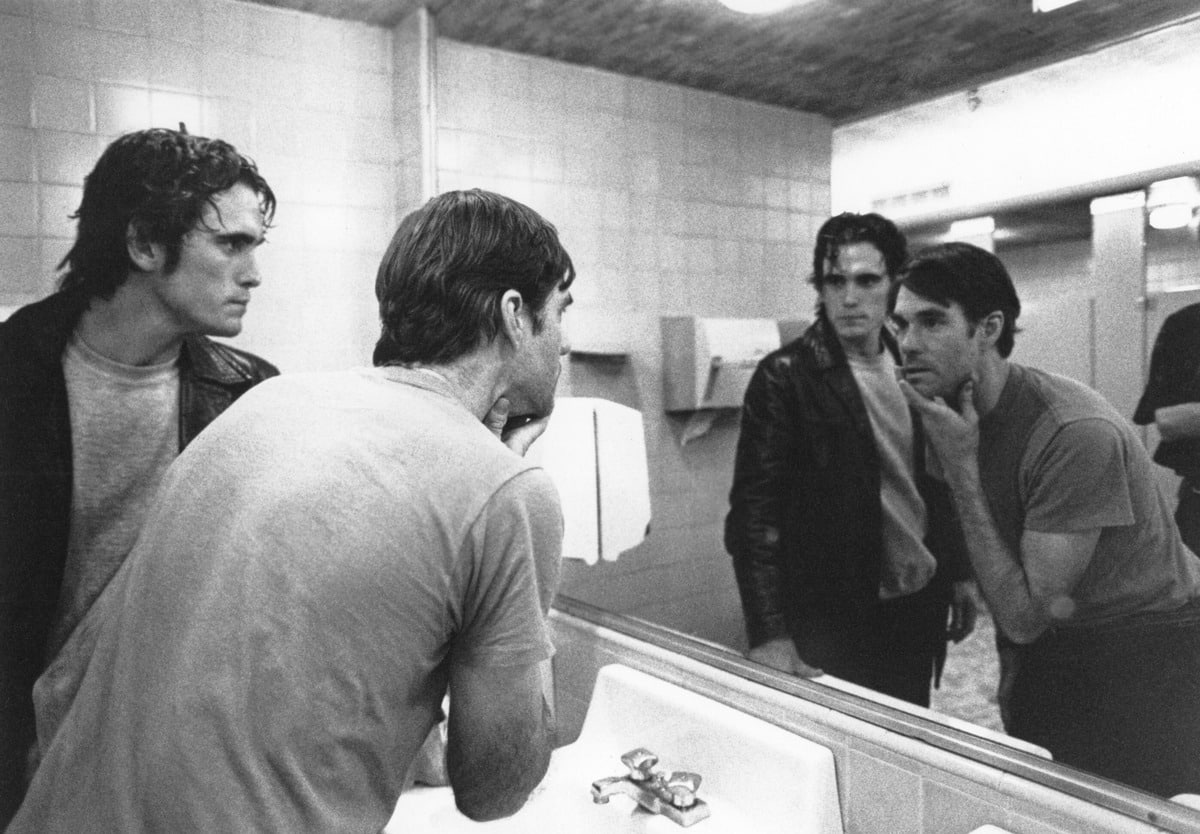

“Fogle’s stories were really funny, and they were authentic. They spoke from experience,” Van Sant tells me. Authentic was the word that would come to define Drugstore Cowboy’s appeal. These characters weren’t your typical stereotypes of sniffling, uninspired drug addicts—they were larger than life, charismatic, and ambitious. Yost, who remained a life-time friend of Fogle, describes Fogle’s novel as autobiographical. In his eyes, the inmate writer behind the film was: “Someone who was loved by everybody that knew him. That doesn’t mean he wasn’t a criminal.” During my conversation with Parker, she mentions that some of the most interesting screenplays she’s ever read were by prisoners. By this metric, Fogle was a shining example, a man who lived adventurously and had stories to tell. In Yost’s account, Fogle “used prison as his office. It was the only place he could write.” Van Sant and Matt Dillon (who had signed on to play the film’s lead) were all ears. They would visit the penitentiary together to pick Fogle’s brain, both of them characterising the visitation room in Walla Walla by the paintings that hung on its interior. “The decorations in the room were pictures of all the famous walls of the world, like the Berlin Wall,” Van Sant laughs. “Because the town is called Walla Walla.” Dillon adds, “I thought, that’s a strange place to put a framed painting of The Great Wall of China. Some sort of subliminal message to the inmates that you’re never getting out of here.”

These early meetings with Fogle formed the backbone for what was about to become Drugstore Cowboy. His stories went beyond his novels, with Gus recalling a particular anecdote that always stuck with him: “He had first gone into prison at 13 in Wyoming—it was the 50s, they didn’t care, they just threw young people in the slammer— and during his sentence he had escaped in the middle of the night from this Wyoming prison. They were running across the desert in pitch black, being chased by a convoy of guards and dogs, and they had a pretty good lead. Then all of a sudden, a bright light lit up the whole desert and exposed them. And the convoy just drove into the middle of the desert and picked them up and brought them back. They didn’t understand what the light was until the next day, where they read in the papers that it was one of the first nuclear tests. They had been exposed by a nuclear bomb.”

Though Fogle had robbed his fair share of drugstores, contrary to popular belief, the Drugstore Cowboy’s protagonist Bob was actually inspired by a friend of his—Brian Ward, the most notorious of the Drugstore Cowboys. “Fogle told me that the character was based on a guy who looked just like me,” Dillon said, after admitting that there was initial concern that he was too young to play the role. “He came from an Irish-American family, and [Fogle] said “as bad as I was, this guy robbed 200 drugstores more than I did.” Ward was Fogle’s original inspiration for Bob’s unhealthy obsession with superstition in the story, namely the now-iconic hat-on-the-bed scene. “He inherited that paranoia from his mother,” Dillon says. “After playing Bob I became obsessed too. I still freak out if I accidentally put a hat on the bed. I’m not saying I believe it, but I don’t mess with fate, either.”

GETTIN’ THE GANG TOGETHER

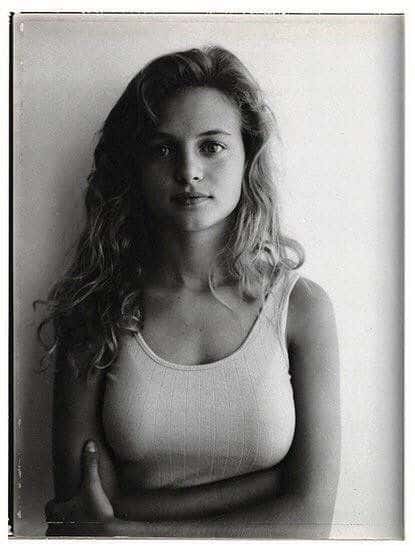

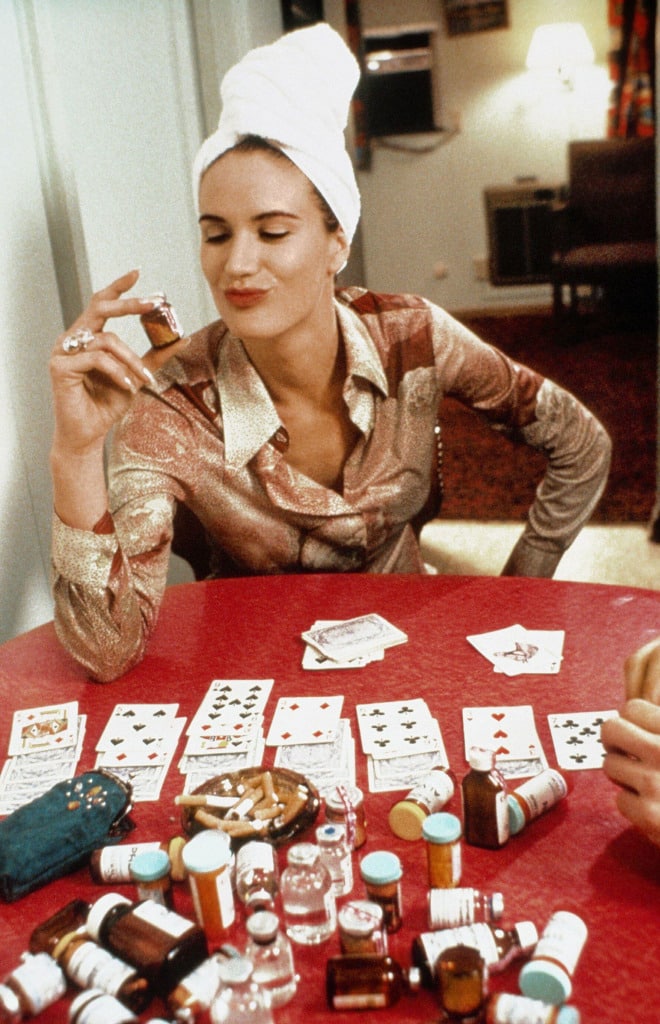

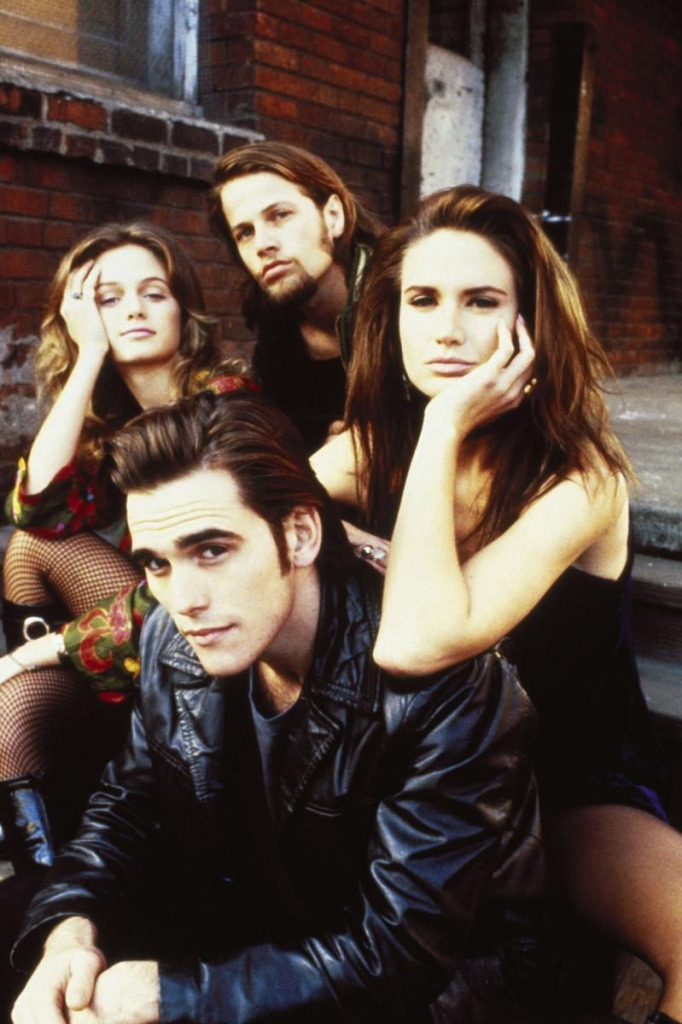

It’s hard to imagine anyone playing Bob better than Dillon, who brings an astounding amount of heart to a character that, by and large, should be impossible to empathise with. Van Sant’s original choice for the role was musician Tom Waits while others rumoured to be in line to were Jack Nicholson (who apparently declined the role in a heartbeat), Sean Penn, and Bob Dylan (Gus disputes this, but says he wishes he came up with the idea at the time). Waits had already accepted the role, but the studio wanted a lead who could win an Oscar, and Dillon fit the bill, having already expressed interest in working with Gus after he saw Mala Noche. Once Dillon was cast, Gus had free reign to cast whomever fit his vision for the film. He famously took polaroids of every actor who came to audition, from Heather Graham—who plays Nadine in the film—to James Le Gros—who plays Rick—both members of Bob’s crew of drugstore thrifters. ‘It was a Warhol-type thing,” says Nick Wechsler, Gus’ one-time manager and a producer on the film. “He would pin them up on the wall, and the energy they were giving him helped him decide who to cast in the movie. When Heather Graham pulled up—her polaroid just popped.”

Kelly Lynch, on the other hand, didn’t need a polaroid to know that she was born to play the role of Janet, Bob’s lover and partner-in-crime in the film, and the moment she saw the title hanging on a wall in her manager’s office, she knew it would be hers. The problem? Lynch was a gorgeous blonde and the character called for a junkie brunette—a rough, Patti Smith type. “What experience do you have with that?” Kelly recalls her manager asking. “Here’s the thing,” she replies, zooming me from her California home. “In 1981 I was hit in a head-on collision—the other driver went the wrong way on a freeway and hit me head on, and I was in a hospital for a year…I saw these lights coming at me and I went “Fuck!” and went through the windshield, the steering wheel came down and snapped my legs in two, and then the dashboard accordioned my thighs. They almost had to amputate my legs.” At the hospital, the doctor would inject a shot of demerol into her hips every four hours. Then they gave her Percodan. Then Talwin. Percocets. Morphine. As Kelly puts it, she became a complete, 100% junkie. “Instead of stepping me down, they completely took me off of them, and I went through a screaming withdrawal that lasted about three days—it was like going into the bowels of hell. So I told my agent that I did know what being a junkie was like, and I’m absolutely right for this part. I went into the audition and got the part the very same day.“

“I went through a screaming withdrawal that lasted about three days—it was like going into the bowels of hell.”

Kelly Lynch on Drugstore Cowboy

Dillon would also use his brushes with drug culture to inform how he approached the role. Though he never used himself, he spoke to friends from back home in New York who knew addiction intimately. Characters like Railroad Johnny: an energetic addict working on a railroad in Harlem who Dillon claims would throw down his tools and walk four blocks to the shooting gallery to blow some holes in the wall. “He would take me through his routines,” Dillon explains. “He would tell me about his life, getting high, getting in trouble. He was an angry guy, but he wasn’t that picture of a passive, feeling sorry for himself type of addict.” Then there was a friend of Dillon’s who actually went to jail for robbing drugstores. “He was a lifelong Manhattan guy,” Dillon laughs. “So he couldn’t even drive a car. He’d rob a drugstore then jump in a cab.” He also kept a correspondence with Brian Ward, who had become a running enthusiast while he was in prison. “He was Mr. Healthy and Clean, a fitness freak when he was incarcerated. Of course, he got out and a short time later he died of a drug overdose, as you might expect.”

With the four central ‘cowboys’—Bob (Dillon), Janet (Lynch), Nadine (Graham) and Rick (Le Gros)—finally assembled, rehearsals for the film could finally begin. But this wasn’t your average table read. Instead, the actors and Gus would drive around Portland for hours, in character, staking out drug stores and shooting the shit. Gus even refers to a small car accident they experienced during one of the rehearsals which led to them driving back to set in a near-totaled station wagon (he mentions immediately after that he hasn’t rehearsed this way since). “What Gus wanted from those rehearsals was for us to become a family, so that when we got to shooting 19 year-old Heather Graham wouldn’t be starstruck around Matt Dillon.” Says Lynch. “We had gotten over those things, and we became a coven of actors who were hanging out and saying these lines and playing around together. That I thought was genius.”

Like Mala Noche before it, and My Own Private Idaho after it, Drugstore Cowboy would be set in Portland, Oregon, a place that had somewhat adopted the Kentucky-born, LA-based Van Sant as its own. Portland had a certain magnetism that pulled the director into its orbit, and it remains a home for him to this day. The city was a bohemian enclave. It was the home of writer John Reed, and it was Portland’s Reed College that Kerouac wrote of in The Dharma Bums. The city had as much to bring to the story as the cast inhabiting it. “There was always this side of Portland that attracted and encouraged Bohemia,” he says. “It was a comfortable place to go if you didn’t have enough money to live in your city. You could always find cheap places in Portland.” In other words, a perfect home for Drugstore Cowboy’s merry band of criminal outcasts.

THE KING OF THE BEATS

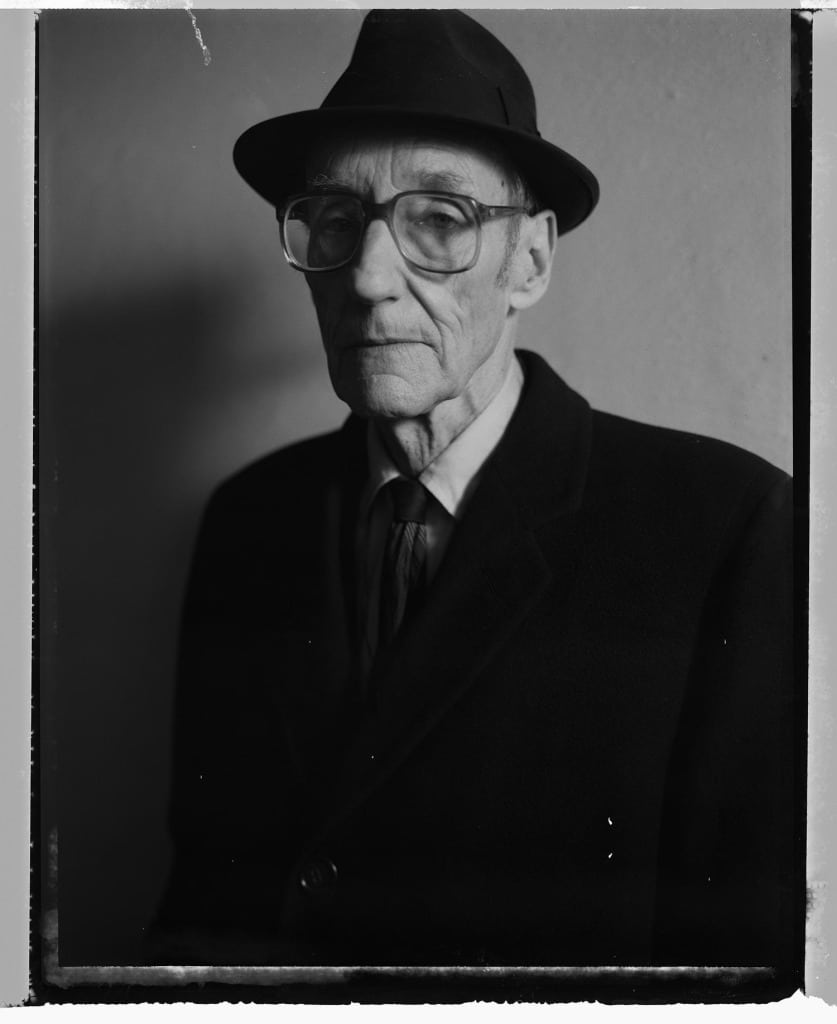

Then there was William Burroughs, who appears in the film as ‘Tom the Priest’, an older ex-drug addict who councils Bob during his attempt to get clean in Drugstore Cowboy’s final third. Although, in the original script, he was just ‘Old Tom’. “This guy doesn’t have much going for him,” Burroughs had told Van Sant. “How ‘bout we call him Tom the Priest?” That wasn’t the only thing he changed about the role, Van Sant tells me. He basically re-wrote his entire part, which Van Sant was more than happy to oblige, more relieved than anything that Burroughs had accepted the role. The director had admired Burroughs for years, along with the likes of Andy Warhol, Tom Robbins, Tom Wolfe, and Ken Kecey. “These were his avant-garde heroes.” Parker says. “He wanted to be around them, and so he would offer them roles.”

At the time, Burroughs was already a counterculture superstar, and a genuine celebrity. He became a legend of the Beat Generation with novels like Queer, Junkie and his quintessential 1959 Naked Lunch, but by the late 1980s, Burroughs’ mythology was being embraced by new subcultures. “He wasn’t willingly the leader of the Beats, but he was made their leader by Berg [Allen Ginsberg] and Kerouac,” Van Sant says, still a little starry eyed. “And then he moved to New York, and would perform in punk clubs. He would read his poetry before the Ramones went on. And so he became king of the punk rockers, too.” Strangely, recruiting Burroughs for the movie went smoothly, owing to a previous interaction between Van Sant and the writer in the 70s in which he adapted one of his stories into a short film. “He was in New York, and his name was in the phone book, so I thought the best way was to really go and visit him and ask permission to adapt his story. Because he was famous in the Jack Kerouac books—they were always visiting Burroughs.”

An infamous junkie himself, Burroughs was a perfect fit for Tom Murphy—a fallen angel with a poet’s tongue, referred to by Dillon’s character as “Benevolent Father Murphy, the most notorious dope fiend on the coast”. Some of the most prophetic lines of dialogue in the movie belong to Burroughs’s Father Murphy:“I predict in the near future right-wingers will use drug hysteria as a pretext to set up an international police apparatus.” Burroughs performed all of his scenes on strong doses of marijuana, which the director had to hunt down himself. According to Van Sant, he claimed it was the only way he could remember his lines, which the director, ever the Beat aficionado, points out was antithetical to most of his writing. “He was always saying that he never smoked marijuana, and he hated it. It gave him the fear. He would always talk like that. I guess by this time, when he was around 78, he learnt to smoke. Though you could never really tell with him if he was high or not.”

Ask any of the cast and crew of Drugstore Cowboy about Burroughs and they’ll probably have a story for you. Laurie tells me about the time she and novelist Tom Robbins were tasked with scoring for him while doing press for the movie. “Burroughs was ill one day,” she says. “He was sick, and he had to get well. And ‘getting well’ meant that you needed some heroin or methadone or whatever. We had Satan on speed dial. He was a drug dealer with a hell’s angels kind of vibe, and we would drop by his house and score from him.” Robbins, an iconic writer in his own right, reportedly had such a good time that he penned Triplets in dedication to that day. In the poem, he writes: I stopped by Satan’s house / I just happened to be in the neighbourhood / Satan came downstairs in a Raiders jacket / His aura was like burnt rubber ‘ but his grin could paint a sunrise / on a coal shed wall. / “I see you’ve met Desire / and Fulfilment,” he said, / polishing his monocle with a blood-flecked rag. / “Regret is in the kitchen making coffee.”

“We had Satan on speed-dial”

Laurie Parker on Drugstore Cowboy

As far as Matt Dillon was concerned, Burroughs was stone-cold sober during shooting. His memories of the poet don’t involve driving around town on side-quests in search of leather-clad drug devils and a score, but he remembers Burroughs having a particular affinity for “lethal things.” Guns, poisonous snakes, explosive devices.. “Bill was a jaded guy,” Dillon recollects,“but he had a lot of curiosities. He once sat there and told me about a snake that rolled around on its ribs and growled like a dog. He would say ‘the snake growled like a dog and, brother, if you got bit by that snake you got a problem.’” Dillon, who had already become acquainted with Burroughs during a prior movie shoot in Kansas, was one of the few on the set to see a warmer side to the Beat King. “He would have a martini at the end of his day. How funny is that?” Dillon laughs, before proudly recalling how for years after Drugstore Cowboy he would receive annual Christmas cards from Burroughs. “And it was in his handwriting so I knew it was legit,” he says, just in case I don’t believe him. “He had a distinctive penmanship.”

THE AMERICAN INDEPENDENT

Talking to the cast and crew about the production of a film that came out almost three and a half decades ago, there’s naturally going to be a rashomon-esque conflict of memory. I hear the same story four times with four different endings. One thing everyone can agree on, though, is that Gus Van Sant is a genius. It’s an easy statement to make from this vantage point, with a varied career and an independent cinema movement to put under the magnifying glass, but not everyone believed it at the time. Until the screenplay landed at Avenue Entertainment, where the newly hired Laurie Parker got her hands on it, Drugstore Cowboy received rejection after rejection. “We were coming out of Nancy Reagan’s anti-drug campaign, and people were rejecting this script because of that.” Dillon explains. “I spoke to actors who were telling me ‘I can’t believe you’re making this movie’, people who thought it was immoral to tell a story that humanised the drug user. It speaks to the times we were in.”

It’s no surprise that so many actors and studios wouldn’t touch Drugstore Cowboy with a ten-foot pole. Here’s a screenplay written during the height of the Just Say No era that actively depicts the euphoria of shooting up, the adventures drug addicts went on just to acquire the drugs, and the rush they experienced in doing so—and not only that, but it did it all with a wry humour that pointed out the absurdity of it all. “When we were doing the movie people were saying ‘Oh, it’s so sad, it’s so difficult, the life of a junkie’ and we were all laughing for most of the movie.” Lynch says. “We had a great time making it. Because for the most part, this kind of junkie doesn’t wallow in their pain—it’s one caper after another. And sometimes people die, and things happen, but you’re so medicated that the truths of the hardships of life don’t penetrate your soul in the same way.”

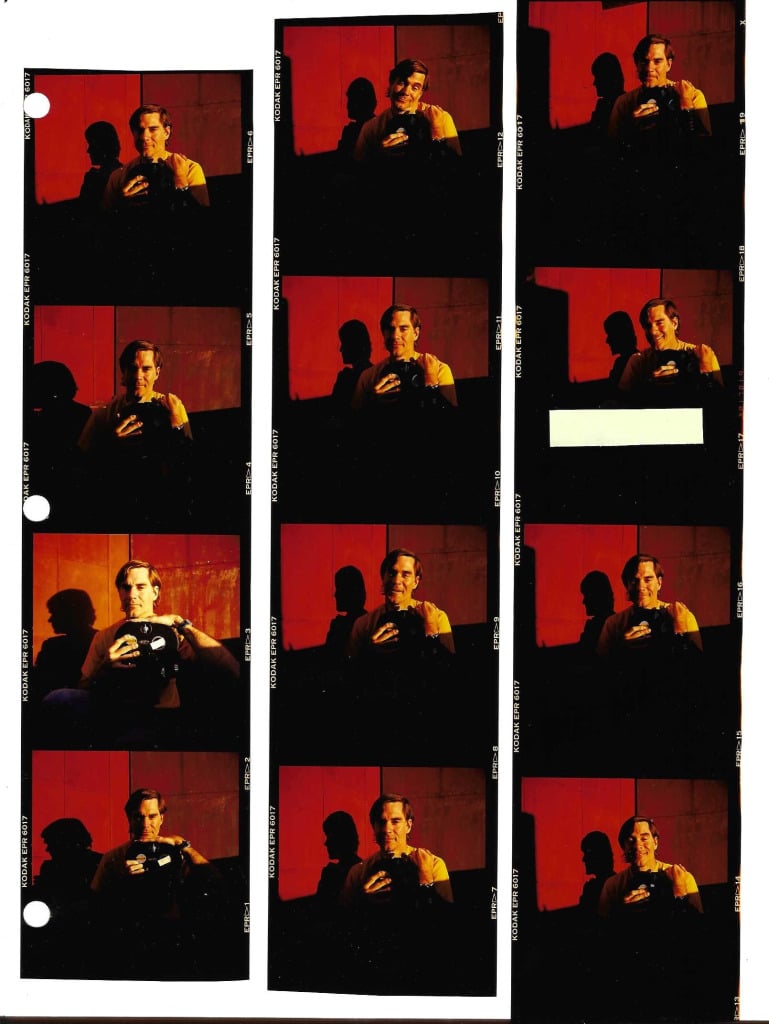

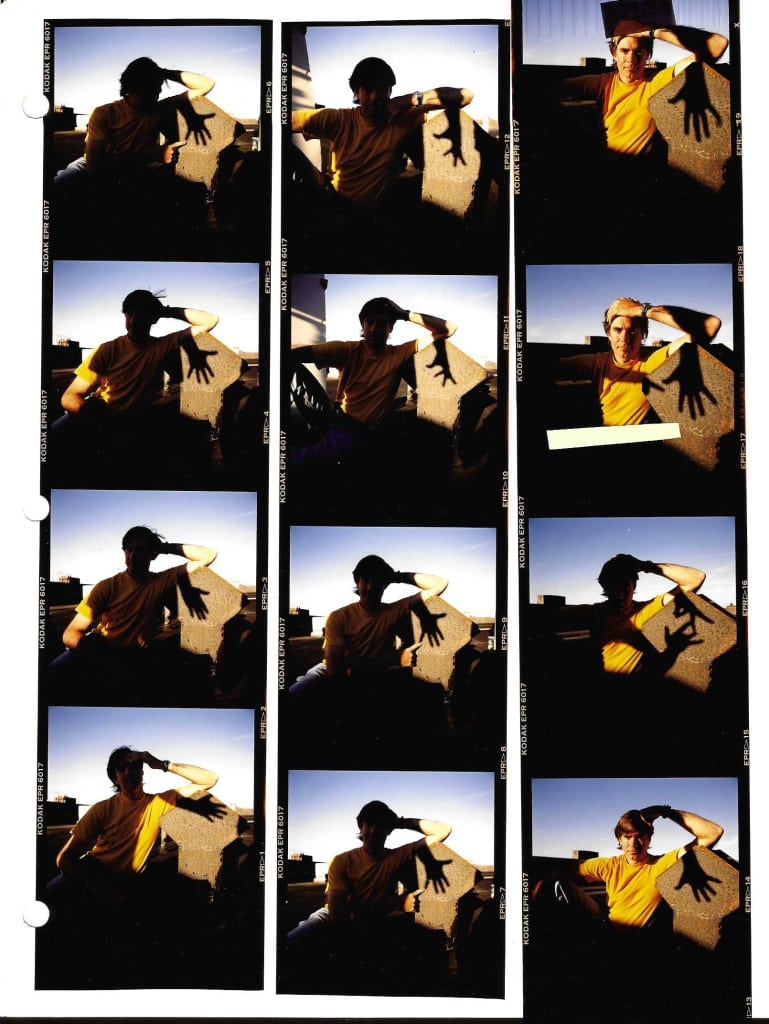

Moreover, Van Sant brought an independent filmmaker’s sensibility to the studio feature, and a radically different energy to the filmmaking process that financiers and even some members of the crew weren’t ready for. “When the director is new and they have yet to prove themselves,” Parker says, “all the ways that they want to innovate are seen as breaking the rules. And all those breaking of the rules are seen as ignorance and poor training.” Van Sant remembers there being whispers on the lot about whether he had it in him to complete the feature. To some, he was too young, too laidback, and too DIY. In fact, Van Sant admits that the three million dollar budget was more a hindrance on him than anything. The large crew afforded to him by the studio only made the day less productive; on his four person crew on Mala Noche, he could get 90 setups in a day. On Drugstore, with an 80 person crew, it was more like 13 setups. “Everything that we did, there was a hold-up,” he sighs. “I was getting in trouble too because we were falling behind on schedule.” The shorter, high-intensity days brought on by the sheer scale of production rendered Van Sant’s typical storyboarding useless. He had to change the way he worked to keep up. ”I’d read about Kubrick doing it: You rehearse first, then when you have everything blocked, then you decide where the camera can be and what the camera can do. So I devised this little trick where I realised that if I moved the camera into 10 different positions during the shot, it still only took 30 minutes to light. So I could get a close-up, a medi shot, a wide shot in one scene at the same time it would usually take to light just one close-up. That changed my perception of filmmaking. I haven’t gone back to storyboards since.” This new, fluid way of working became a mode of artistic liberation for Van Sant and the actors, who were now open to improvising and moving freely within the scene. He encouraged kinetic filmmaking. “It was his idea for us to shoot the home movie that bookends Drugstore,” Dillon remembers. “He put the camera in our hands—mine, Kelly and Jim. The best directors are always open to what falls in front of them. I’ve seen it with Francis Ford Coppola on The Outsiders, I saw it with Lars Von Trier on The House That Jack Built, and I saw it with Gus with Drugstore Cowboy.” Like the rest of the crew, Dillon speaks of Van Sant with reverence, calling him the genuine article, a real artist, and that while the director seemed laidback, there was never any doubt that it was his movie.

Van Sant himself keeps an admirable modesty about his work throughout our entire discussion. I mention that Premier Magazine once named Drugstore Cowboy one of the most daring films of all time for the way it handles its subject matter, and he’s quick to point out that Charles Dickens was telling stories about the streets of London a century earlier. When I ask Lynch to describe what she admired the most about Van Sant’s sensibilities as a filmmaker, she said: “Gus looks at disenfranchised people with a dignity meeting gritty reality, and that’s a tough tightrope to walk. You’re either being preached to or you’re being told that these are bad people. But Gus allows things to live. The humour, the sadness, the horror, the weird coincidences of life. Putting all those elements together is pure Gus Van Sant.”

Once Drugstore Cowboy was released in 1989 it brought an enormous amount of vindication for Van Sant. It earned him a blank cheque to do whatever he wanted to do next, and his third feature My Own Private Idaho was a film that took bigger risks and reaped bigger rewards than anything he had done before. A story with heavily queer themes, it contributed to the blooming New Queer Cinema movement that included Todd Haynes, Gregg Araki and Van Sant, who was openly gay himself. Parker, who also produced My Own Private Idaho, recalls a conversation with Van Sant that tells you everything you need to know about the filmmaker. “When I asked him why he wanted to make that movie, he said he really wanted to fail. He wanted to do something risky, and hard, that he could fail big at. And I thought, that’s badass, that’s where I wanna be, exactly in that realm. Things aren’t worth doing unless you can really fail big.”

My Own Private Idaho may be the most complete, defined product of where Van Sant’s interests lay in his early career, and Mala Noche may be the most purely electrifying (call me a sucker for first features), but Drugstore Cowboy’s legacy remains undeniable. “It helped herald in this independent film movement that came after Jaws and all these blockbusters of the 80s. It barely got made at the time, and it would not get made now,” Lynch says. “Unless you had Tilda Swinton playing my part and Timothee Chalamet playing Bob. You’d have to cast these ‘great indie superstar actors.’ You couldn’t just discover a Heather Graham or a James Le Gros, or me, or a Gus Van Sant.” When Dillon talks about starring in the movie, he describes it as one of the proudest contributions of his career. “It’s hard to see yourself in those early movies. Sometimes you look at old movies and it feels like seeing a picture of yourself as a kid, you’re almost unrecognisable. With Drugstore Cowboy, I still see myself. That was a moment for me.”

Van Sant is surprised when I tell him about the multitudes of Letterboxd users that have Drugstore Cowboy in their Top 4s, though it only takes a moment of quiet introspection before he summarises exactly why he thinks the film still has a place in youth consciousness, despite it being so of its time and place. “I keep remembering that, yes, it’s about drug addicts, but it’s also really just about people that have uncertain futures. Bob has all these theories of how to live with an uncertain future. If somebody talks about dogs too much, then you got to lie low because then you brought a hex onto the group. And so, they have to chill out for 30 days until the hex is gone. He had the philosophies of a person that had to figure out their own system of survival. And I think that applies to a lot of young people, still. It’s always been about survival.”