The opening shot of Louis Malle’s Elevator to the Gallows (Ascenseur Pour L’Échafaud, 1958) is an extreme close-up of Jeanne Moreau’s face. At first she is cast in darkness, her closed eyes lit with a triangle of light. Like the beginning of a play, the lights come on, revealing the rest of her features. Tilted stage right, this cinematic close-up allows us to see every pore. A smear of a tear sits under her eye, echoing the shine above her rouged lips. We hear the grain of her breath as she inhales and opens her eyes, glittering with the reflection of a spotlight. “I’m the one who can’t take it any more,” she says. “I love you, I love you.” As the camera zooms out, we realise she is talking to her lover, Julien, whom she has persuaded to kill her husband. “Without your voice, I’d be lost in a land of silence,” he responds, frantically. Their plan is thwarted when he is trapped overnight in a lift, during which time he is framed for another murder he didn’t commit.

The term femme fatale can feel like an empty signifier. It is bandied around, much like other French expressions (faux pas, raison d’être, déjà vu) in a way that feels generic. A beautiful woman with the ability to destroy and bewitch men, she is an archetype in the Jungian sense, located in our collective consciousness, descended from Eve, Salomé, and Lady Macbeth. She is sexual and symbolic, a plot device to bring out the hero’s destruction and reflect male fears and desires.

As Florence, however, Moreau’s femme fatale feels different. What is striking in these opening scenes is exactly how specified she feels, how fleshed out. The close-up of her face reveals an intimate psychology that has us immediately enthralled. Malle was inspired to cast Moreau in the role after seeing her in Tennesse Williams’s play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. Up until then her success as a film actor had been limited. The daughter of a barman and a Folies Bergère dancer from Lancashire, Moreau had been cast as starlet types in commercial films (such as Jean Gabin’s 1954 crime thriller Touchez pas au grisbi), heavily made up to cover what she described as “the rings under my eyes and my asymmetrical face.” She fitted what film professor Ginette Vincendeau describes as, in her obituary of Moreau, Malle’s desire for “a more cerebral type of female eroticism, based on the face rather than the body.”

In Ascenseur the beauty of Moreau’s ’imperfections’ are laid bare, complementing the depth of interiority that is afforded her, her thoughts in voiceover as she aimlessly wanders the streets of Paris. In 1985, Gilles Deleuze would go on to define the time-image—a regime of images in cinema that were no longer subordinate to action, allowing affect to come flooding in. In the most beautiful, central sequence of the film, it is night; Florence walks, an illuminated sign for Kronenbourg beer flashing at her, on and off, before the syncopated rhythms of Miles Davis’s trumpet starts. She moves past shop windows and bars, weaves through traffic imperfectibly. Dressed elegantly in two suits designed by Chanel (a uniform for the cosmopolitan French woman), her existential crisis is a forerunner to that of Corinne Marchand’s as Cléo Victoire in Agnès Varda’s Cleo de 5 à 7 (1962)—a deadly woman in a different sense. “What goes through her mind and her heart,” is “so powerful,” said Moreau of Florence in 2005, “that while she walks in the streets she looks like a madwoman, even speaking to herself.” Her virtual potential is only highlighted by the secondary plot—a young couple who steal Julien’s car and go on the run—living out a Hollywood-style adventure while Florence continues her street haunting, mourning her missing lover.

The film ends with Moreau’s meditation on love, death, and photography, as photos of the couple—evidence of their affair and proof of their crime—develop: “No more ageing, no more days… Here we are together…They can’t keep us apart.” Malle’s influential film is often celebrated as a precursor to the French New Wave and many others jumped at Moreau’s potential to be a new kind of femme fatale. In 1963, she took the lead role in Jacques Demy’s La Baie des Anges as Jackie, a divorcée with a gambling habit who seduces a young salari. called Jean. In contrast to Malle’s film, Demy opens with an image of Moreau walking along a beach promenade. Framing her with a circle as if viewed through a telescope, the camera moves into a quick backward travelling shot, zooming out until she is invisible.

Whereas Malle was concerned with portraying Moreau’s interiority, Demy was concerned with emphasising her opacity. It is by far Demy’s darkest film, set in the casinos of the French Riviera, and Moreau has a glamorous appearance that seems designed to conceal: white suit, peroxide blonde hair, face powder, a pencilled beauty spot, fake eyelashes. Jean first sees Jackie from a distance, being kicked out of a casino for cheating, and throughout the film we never get beneath her surface (she keeps her heels on, even on the beach). While gambling quickly presents itself as a metaphor for love, the risks of romance, the highs and lows of passion, (“When I met you I’d lost everything,” Jackie tells Jean,) Jackie’s love for gambling doesn’t represent anything other than gambling. It is her one and only vocation: “The first time I was in a casino I felt like I was in a church,” she tells Jean, who she objectifies as a “horseshoe,” her good luck charm. While this might be read as a reductive character portrayal on the part of Demy, it is a brilliantly realistic representation of an addict’s psyche, the work it takes to keep up the lies, to fuel a vice, and how it shapes a whole world. When Moreau does reveal a sense of interior shame—“I am rotten on the inside, I dirty everything I touch”—it is more moving for how unlikely the admission feels.

On the cusp of a sexual revolution, and over a decade after the release of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1949), in 1960s France the femme fatale served to highlight new anxieties around emasculation and changing gender roles. Take Patricia in Jean-Luc Godard’s À Bout de Souffle (1960), who eventually betrays her lover, runaway criminal Michel. Her writerly ambitions and masculine-coded style (most notably the short cropped hair) jars with the machismo of Michel, who used to be an air steward for Air France and admits to liking the idea of being a gigolo. In Claude Clouzot’s La Vérité (1960), Brigitte Bardot plays Dominique, a Left Bank denizen who is put on trial for the murder of her former lover. While Dominique’s beauty is constantly referenced, the prosecutor makes reference to the fact that she smuggled de Beauvoir’s Les Mandarins (1954) into school as a sign of her moral perversity. The philosopher herself described Bardot as a liberated “locomotive of women’s history.”

On the cusp of a sexual revolution, and over a decade after the release of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1949), in 1960s France the femme fatale served to highlight new anxieties around emasculation and changing gender roles.

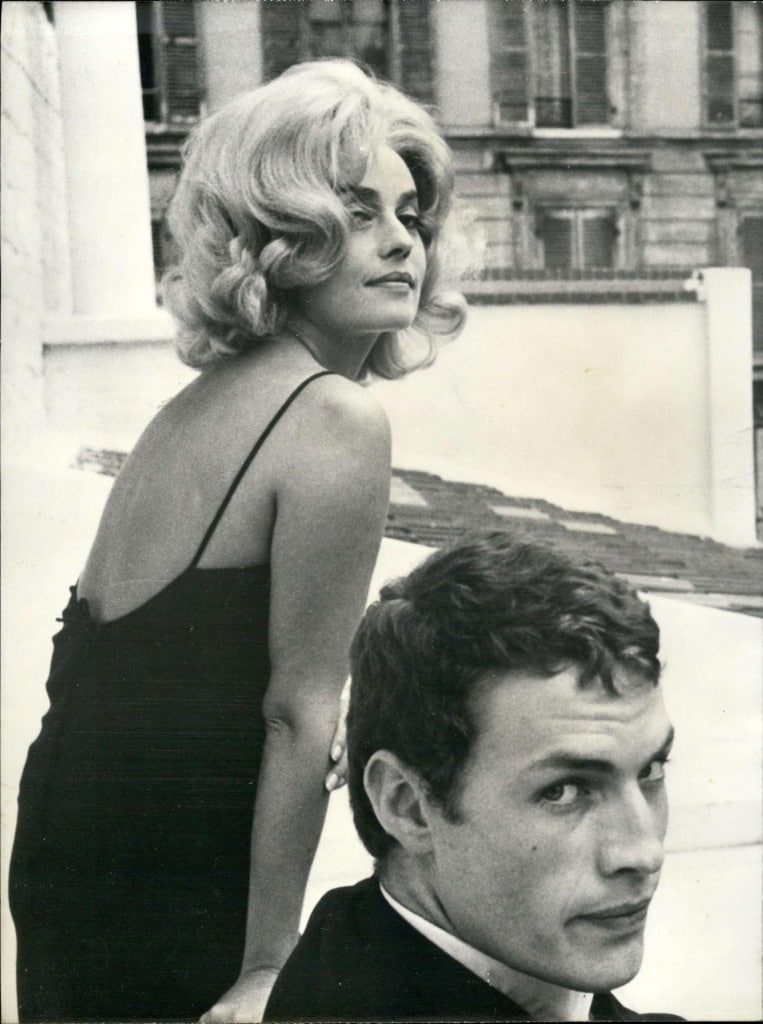

Jeanne Moreau

It was in her role in François Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1962) that Moreau joined this line-up of femme fatales for a new age. Perhaps enamoured by her performance in Elevator to the Gallows, Truffaut cast her in The 400 Blows (1959), in a cameo as a woman wandering the streets of Paris at night, having lost her dog. While the young Antoine Doinel tries to help, an older man, perceiving Moreau’s beauty, intervenes.

Jules et Jim is a film that explores the possibilities of love beyond the marital contract. Moreau plays Catherine, a spirited woman who falls in love with the two titular friends (and they with her). The fin de siècle setting only emphasises the feeling that Catherine is some kind of alien from the future. In the film’s most reproduced sequence, Catherine dresses up in masculine clothing, draws on a moustache, and challenges Jules and Jim to a running race (which she wins). While the men attempt to contain her with language and metaphor (they compare her to an ancient sculpture, call her an “apparition”), Catherine’s on-screen vitality and velocity challenge any ossification. As a femme fatale there is a sense she is writing her own script. The song she sings to her lovers refers to the femme fatale in the third person: “She had eyes, eyes like opal / That fascinated me… The oval of her pale face / Of a femme fatale who was fatal to me.” Singing the masculine part while representing the feminine object, she is everything—everyone—at once. “In my opinion, it’s too good for them,” she quips. “But then we can’t choose our audience.”

Not every Moreau film presented her in such a nuanced way. As the title suggests, Joseph Losey’s Eva (1962) is a more on-the-nose depiction of the femme fatale archetype and literally opens with a passage from Genesis. Moreau’s taciturn title character is a reductive metaphor for the failed writing ambitions of Tyvian (played by Stanley Baker)—at one point she crawls on the carpet, pawing his books off his shelf. Of the film, Moreau only remembered Losey as a “strange man” and found filming in Venice freezing. Inspiring directors internationally—from Orson Welles to Michelangelo Antonioni—Moreau would continue to take on complex female fatale infused roles (she turned down the chance to play Mrs Robinson in The Graduate (1967)), such as Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Querelle (1982) where she plays a glamorous brothel madam. Women “worry so much about ageing,” she said in her seventies. “But I tell you, you look younger if you don’t worry about it. Because beyond the beauty, the sex, the titillation, the surface, there is a human being. And that has to emerge.”