PARIS, France—I am two hours early for my interview with Ottessa Moshfegh. Waking up in London while it is still dark, I arrive zombie-tired in Paris where the sun seems to be shining hysterically. When I arrive at her door at the prescribed time, she sticks her head out of the fourth-floor window to greet me, startling me with an effusive “hello!”

Based in California, Moshfegh is in Paris for several weeks to write, staying around the corner from the Shakespeare & Co bookshop whose approach is thick with tourists on the day I visit. The labels on her building’s letterboxes include ‘Virginia Woolf’ and ‘Gertrude Stein’, as well as other flamboyant names I’m not sure are famous writers or real people. Her apartment is small—lined with a shelf of heavy tomes that seem more ornamental than to be read. From her window, there is a view of Notre-Dame, its back section in a brace of scaffolding; below, a vendor is attempting to sell hot glazed pralines on such a warm day.

“Paris is so much friendlier than I remembered,” Moshfegh tells me. “More relaxed.” The last time the author spent a significant amount of time in the French capital was 10 years ago, for another writing stint that would turn out to be rather important. “That was when I started writing My Year of Rest and Relaxation,” says Moshfegh. Her second novel, published in 2018, follows a beautiful, rich, and misanthropic young woman whose abject goal consists of going to sleep for a year with the help of copious sleeping pills and downers prescribed by a quack psychiatrist. The book was a publishing sensation, as much for its iconic cover—a portrait of a disaffected-looking woman by Jacques-Louis David with the title in fuschia (“fuck you pink” as Moshfegh calls it)—as for its depiction of feminine angst and world weariness.

It is a resolutely New York novel—starting in the Upper East Side art world and ending downtown with 9/11—and I am surprised to learn the novel has origins in Paris. “I probably wrote most of the novel here that month,” says Moshfegh. “In my first iteration of the story she wakes up on a plane to Paris, and is set up by her sleep-self to be in this weird psychosexual drama with someone who locks her in the apartment, and then she kills him and doesn’t know how to get rid of his body— there was a gypsy at the end of the hall. It was bad.” The writing of the novel in Paris coincided with her own intense feelings of isolation. “I threw my back out lugging a suitcase up to the eighth floor of this building. I barely left the apartment. I was very lonely and depressed, and in a lot of pain from the suitcase.”

Looking around Moshfegh’s new apartment, I feel like I am visualising the world in which the book was created. Her laptop sits on a round wooden table, bare apart from a scattering of notebooks, pens, and other unmemorable miscellany. In the corner, a sliding door leads to a small, dark bedroom. “Are you hungry?” asks Moshfegh.

Now 42, Moshfegh was raised in Boston, to a Croatian mother and an Iranian father. After college, she moved to China to teach English, and spent her twenties in New York City working as a literary assistant and doing an MFA at Brown. Itinerancy has defined Moshfegh’s biography. Today, she lives in Pasadena with her husband, a place she describes as ending up in, rather than living in by choice: “I don’t feel like LA is my spiritual home. It doesn’t feel sacred to me.” It is her four dogs (and marriage) that keep her in place. “If I didn’t have them, I literally wouldn’t own a house.”

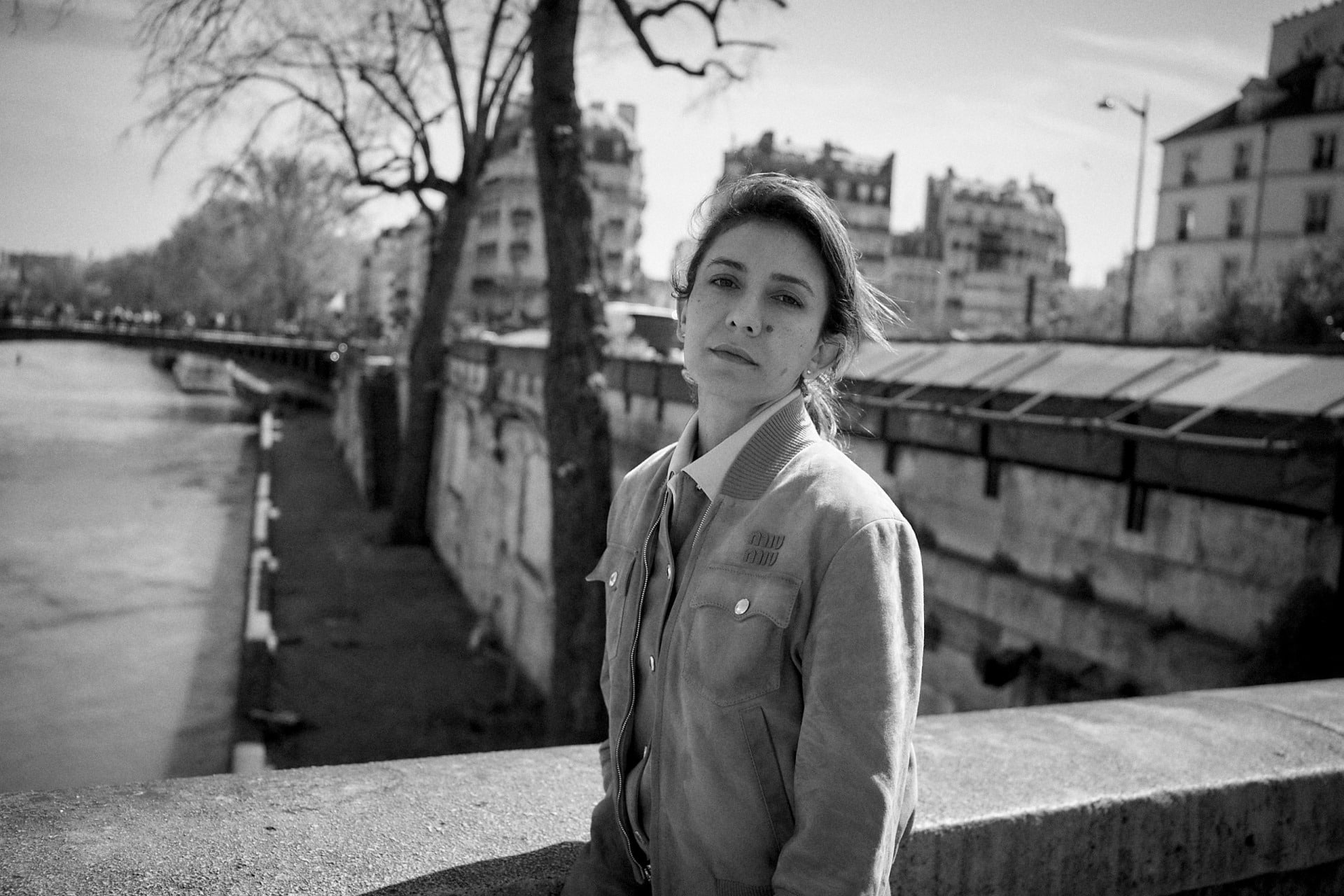

As a person I find Moshfegh kind and empathetic, but also a bit aloof, pursing her lips and taking long pauses before responding. As she tries on the clothes for her photoshoot, she gazes at herself in her tarnished mirror with deep concentration, adjusting the waistbands and shirt tucks meticulously. Clothes are a great interest for Moshfegh, and she tells me she has collected vintage garments since she was an adolescent. She grabs a hat she bought at a vintage boutique in Florence and suggests I try it on. It is a weird hat, unlike any other I have seen before, as if a riding cap in boiled wool had its visor cut off. We face each other in the mirror: on her it looks Soviet, ceremonial. She says it looks more “1920s” on me. “Kind of Great Gatsby,” I agree.

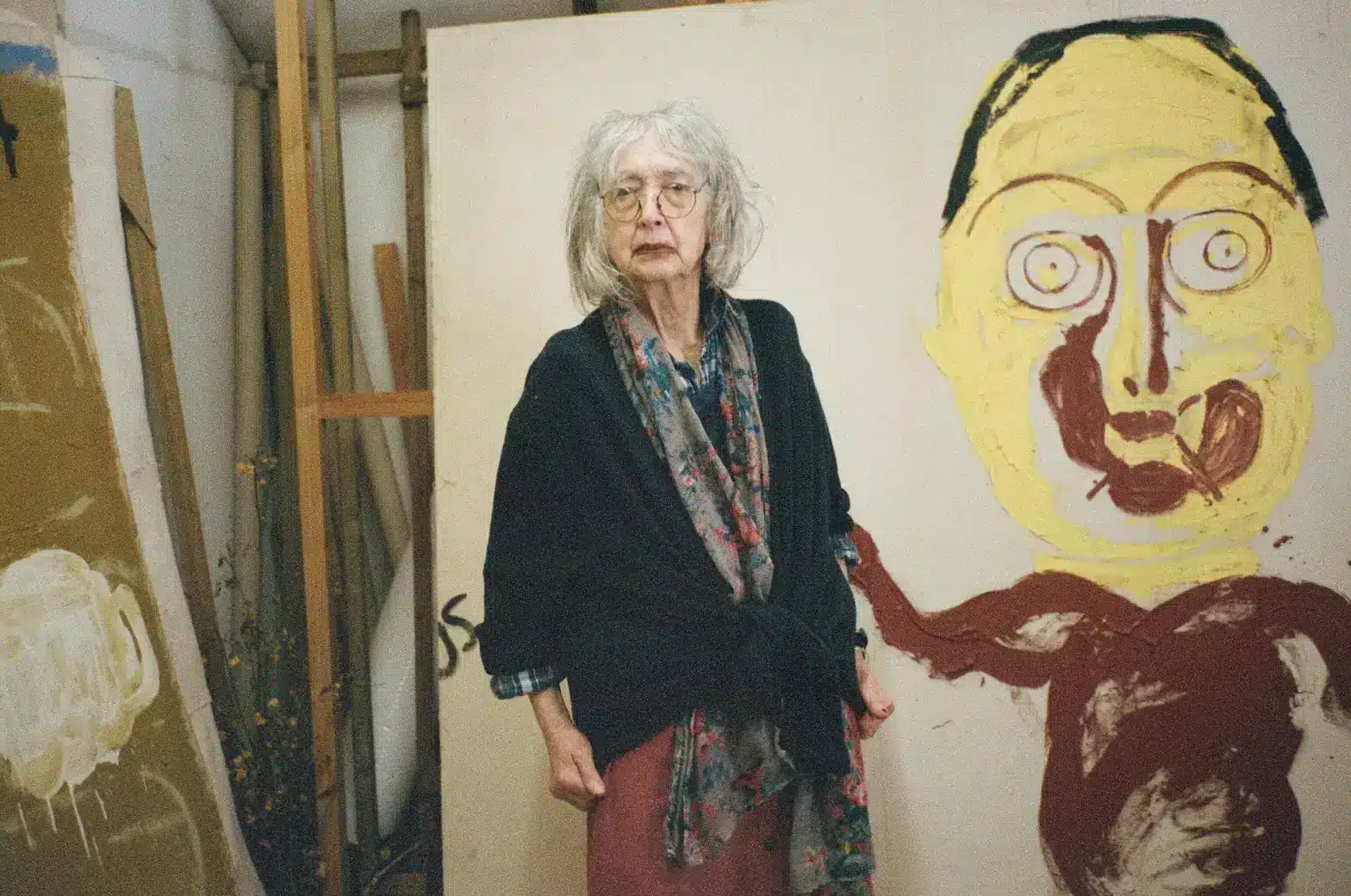

We go down into the streets of Paris. The photographer trails her as she walks through the tourist-heavy traffic and down onto the empty quais, avoiding a smattering of bird shit on the stairs. Moshfegh is something of a paradox, a writer whose work has always dealt keenly with the grotesque, but also a kind of literary It girl, whose image people, magazines, and brands want a part of (she has written journals for Proenza Schouler and done runway for Maryam Nassir Zadeh).

Moshfegh is interested in that gap between appearances and reality. “Our relationship with mirrors is weird,” she tells me. “We go to the bathroom and wash our hands because we want to be hygienic. And that’s when we look up at ourselves, and the mirror is so close. Then you go back to your dinner date, or whatever. How do I say it? It has just always seemed so odd to me that I’m on the inside of a person whose outside you’re seeing, and that I’m not really her.”

I could have written Eileen a totally different way, but it felt very cinematic to me. From the beginning I had Hitchcock’s adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca in mind and I thought, cynically, a novel is something that people buy—it’s a product, sort of like buying a ticket to a movie. I didn’t have that much respect for the literary world in terms of it being an industry.

Ottessa Moshfegh

“The terrain of my face was heavy with soft, rumbling acne scars blurring whatever delight or madness lay beneath that cold and deadly New England exterior,” announces the eponymous protagonist on the first page of Eileen (2016). Moshfegh’s debut novel, it is a psychothriller about a poor, charmless young woman who works in a juvenile correctional facility for boys and becomes obsessed with the establishment’s new psychiatrist, Rebecca. Eileen has an anxious fascination with the externalisation of her own insides, describing breathing as “an embarrassment,” but also taking laxatives to empty herself out. When it was published, Moshfegh received criticism for having written such a disgusting heroine. “No one wanted to relate to Eileen,” she says.

Yet while the protagonist of her follow-up, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, is similarly abject, sleepwalking to her bodega with the gunk of sleep all over her face, the reaction was different. “I knew if I made her pretty, and blonde, and skinny, and rich, I’d be setting myself up for a different reaction,” says Moshfegh. Along with the likes of Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar (1963) and Melissa Broder’s So Sad Today (2016), the nameless protagonist became a spearhead for a popular internet movement known as ‘sad girl literature’, whose groupies idolise their depressive heroines. “Women come up to me at book signings and say how their friends all found each other because of the book; that they thought they were the only one who felt that way. It’s amazing to me because I always felt like my work was so alienating.” I tell her of my own experience reading the novel. First as a 23-year-old unemployed graduate who found her antisocial protagonist aspirational, and then rereading it six years later and seeing her ‘sad girl’ character for what she was: sad. “I think there’s a very young reader of the book that’s not so critical of the character, which fits into this whole sad girl movement,” says Moshfegh. “It bothers me a little bit.”

Moshfegh’s heroine is soon to find more fans, uncritical or not. The author has adapted a screenplay for My Year of Rest and Relaxation and with Yorgos Lanthimos attached to direct, the internet hype has already begun, with rumours circulating that Emma Stone will play the lead. When I ask Moshfegh for details, she is unable to reveal much, although alludes to the fact Margot Robbie is attached as a producer. (Something about the Barbie star being cast in the role feels unlikely but also conceptually interesting). Lanthimos’s brand of weird, baroque cinema also feels like a good match for Moshfegh’s macabre aesthetic. While she didn’t quite get on with Poor Things (2023) (“Do I love stories about infants with women’s bodies discovering their sexuality? It’s not my first choice,”) she loved The Lobster (2015), describing Colin Farrel’s characters in terms that might describe her own protagonist. “It was obvious to me he was super repressed. It isn’t a world without feelings. He is just someone who can’t handle his emotions, his wife leaving him. There was something there I thought was really special.”

Movies are becoming more and more central to Moshfegh’s output. Last year Eileen was adapted into a feature directed by William Oldroyd and starring Thomasin McKenzie and Anne Hathaway, for which Moshfegh co-wrote the screenplay with her husband, Luke Goebel. Currently, she is working on a screenplay of Rachel Kushner’s The Mars Room (2018) and her novella McGlue (2014) has also been optioned to become a movie, with the British director Andrew Haigh attached. “Making a movie is an ordeal,” says Moshfegh of the process. “It’s all kind of up in the air. Everything in Hollywood is up in the air until they’re actually shooting it… you can’t be precious about any one thing because you can have your heart broken if it doesn’t work out. I’m fine with that being the case for a movie, because you can blame someone else. When I write a novel it feels like such a commitment, I couldn’t imagine giving up.”

The pulpier forms of film, television, and commercial fiction have always been present in Moshfegh’s work, from the noirish Eileen, reportedly written with the help of a book called The 90-Day Novel (2010), to Death in Her Hands (2020), her novel about a 70-something woman who watches too many detective TV shows and tries to solve a murder based on a detective story template she finds on her local library computer. “I was trying to see how the formalities of storytelling could become part of my characters,” says Moshfegh. “I could have written Eileen a totally different way, but it felt very cinematic to me. From the beginning I had Hitchcock’s adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca in mind and I thought, cynically, a novel is something that people buy—it’s a product, sort of like buying a ticket to a movie. I didn’t have that much respect for the literary world in terms of it being an industry.” Yet Moshfegh also describes these popular forms as “Trojan horses”, allowing her to “sneak someone you have never seen before into mainstream literature. With Death in Her Hands I was interested in this woman who does not know how to figure herself out, but who somehow projects herself onto this murder mystery and solves it according to the rules of literature.”

A certain irreverence towards high art defines Moshfegh’s own taste. I ask her about Whoopi Goldberg, a ‘character’ in My Year of Rest and Relaxation, whose movies her protagonist watches over and over again on a rented VCR. Her love of Goldberg provides the otherwise charmless protagonist with a redeeming humanism. “I was aware there’s a trope in American storytelling of the magical black person, but Whoopi Goldberg is so amazing. People have forgotten that she was really radical. She was a performance artist when she started and she was so strikingly beautiful,” Moshfegh says, with a real wistfulness in her voice. “I grew up watching stand-up comedy and her body of work is amazing.” The author believes that stand-up is the “highest form of art” and cites her favourites as Eddie Murphy and Richard Pryor. “Before Louis CK got cancelled I went to see him by myself at this huge stadium in Los Angeles and it was amazing. He doesn’t shy away from his own arrogance and he’s really exploring some existentialist shit.” Moshfegh is also a fan of reality TV and, to my surprise, cites the British chef Gordon Ramsay (of Kitchen Nightmares fame) as another hero. “I think he’s brilliant. He is able to recognise a social dynamic and tell someone what they need to hear. He’s like a guru. He wants to teach you a lesson. He actually cares about things like dignity and honour when he’s like, ‘How could you serve that to someone?’,” she explains. “It’s simple and it’s just that he’s a passionate person. I want to write his autobiography.”

Moshfegh’s next book isn’t about Gordon Ramsay, but it is inspired by Britain. A work in progress, it is set in somewhere resembling Brighton (her own grey town is called Dully) in a period resembling the 1990s. She has written a fair amount of it in Brighton itself, but the location serves as more of an ‘elsewhere’ than a specific milieu. “There are too many annoying associations in American culture and I wanted to look at something from a different angle,” she explains. “One of the central characters is a teenage boy who has been court ordered to stay away from his father, and he needs mental health clinical work. I don’t know the social welfare system in England so I could make it up in a way I needed for the story. It just needed to be somewhere foreign.” The soap-opera form has also been an inspiration. “I want it to feel real but also like something that is on cheap television. American soap dramas look so phoney, the storylines are endless. People can do impossible things, like come back from the dead, get away with murder—it’s more like a theatre stage.”

I’ve learned to trust my sense of disgust and I don’t feel as vulnerable to everyone’s shit. If you keep on participating in something you find disgusting, do you get to have dignity? I’m thinking a lot about dignity right now. I might fail, it might be impossible for me. Who knows?

Ottessa Moshfegh

Moshfegh believes kitsch forms such as soap operas can be used to sublimate reality. “It’s a comedy to make things bearable. If your mother started having an affair with your husband and then had a baby, and you realised this was both your stepchild and your sister, you’d be horrified. It would be so incredibly disturbing. In the melodrama version of that, you can kind of handle it.” While all of her books have been defined by their depiction of disgust and the grotesque, perhaps most of all Lapvona (2022), her most recent novel about a medieval village filled punitively with corpses and vermin, Moshfegh feels she is moving away from this interest, a transition that may be coming with getting older.

“Disgust has developed through my work over the different books. But I think Lapvona has brought me to the end of my fascination with disgust. While there’s a fair amount of blood in my book I’m working on now, I don’t think it’s disgusting,” says Moshfegh, getting up to close the window as some flies have just flown in. “Disgust has been a catch-all for me in my youthful times of anything negative. I didn’t have complexity around my feelings, so if I didn’t like something it was just disgusting. I’ve learned to trust my sense of disgust and I don’t feel as vulnerable to everyone’s shit. If you keep on participating in something you find disgusting, do you get to have dignity? I’m thinking a lot about dignity right now. I might fail, it might be impossible for me. Who knows?”

I wrap things up with Moshfegh. It’s late afternoon and the city outside is humming. I feel twitchy with tiredness but satisfied, especially when Moshfegh asks me about my own writerly ambitions, telling me that I just need to wait for inspiration to strike. I leave her at the door, ask her what she is up to tonight. “I’m delivering a script tomorrow,” she smiles. “So I think I’ll take an Adderall and do that.”

Production by Anna Pierce. Styling by Broad Peak Studio. Ottessa is wearing Miu Miu.