Gilda greeted the first Cannes Film Festival audience with a new type of morally ambiguous story, becoming a definitive example of film noir—complete with its iconic Rita Hayworth performance. In this essay, Peter Bradshaw explores the love story in which hate is the biggest aphrodisiac.

The Cannes Film Festival launched in 1946, a sparkly circus tent of movie enchantment erected on the fashionable French Riviera. It was a rebuke to the fascists who’d been running the festival in Venice. The first Cannes had been planned for 1939 but had been abandoned at the very last moment due to Hitler’s invasion of Poland.

The Hollywood pictures on offer at Cannes in 1946 were rather different to the experience pre-war European audiences had come to expect from the American dream factory, known for its wholesome glamour, entertainment, escapism, comedy, romance, and drama, which always found a moralistic resolution. French cinemagoers and cinephiles had been starved of Hollywood, and, when the backlog was released, they were reportedly thrilled by the new darker, more exotically pessimistic and sexually subversive fashions in moviemaking. In the Cannes competition was George Cukor’s Gaslight (1944), with Charles Boyer as the manipulative husband trying to drive his wealthy wife mad, remade and intensified from an earlier version and Patrick Hamilton’s stage play. There was Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend (1945) with Ray Milland as the dangerously self-destructive alcoholic, and Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946) offered a tortured love story between Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman, replete with pain and hurt.

Most sensationally of all, Cannes audiences saw Charles Vidor’s Gilda, starring Rita Hayworth, a dark and disturbing love story, or rather a hate story—a criminal adventure about men electrified by their hatred of women and themselves. Vidor’s movie was in the vanguard of the gloomier, realer, and more disillusioned strain of melodrama—tales from the shadows influenced by the German expressionists, exulting in their fusion of sexual obsession and crime. French critic Nino Frank that year coined the phrase “film noir”, which, like the Italian “giallo”, originated from the pulp fiction of the day. It was not a term the Americans would have recognised, but it was one of two French phrases, noir and femme fatale, which became indispensable for describing this kind of film. And Gilda was there at the beginning: Gilda heralded the nightfall of noir.

Glenn Ford is Johnny Farrell, a louche American chancer in wartime Buenos Aires who cheats recklessly at dice and cards, saved from a brutal back-alley beating one night by Ballin Mundson, played by George Macready, a kind of ambiguous Nordic-Germanic gentleman wielding a sword-stick. Ballin offers Johnny friendship, of a brusquely impulsive sort, and a job managing his illegal private casino club, whose crooked roulette wheel is used for discreet payoffs, including cash to suppress a potential competitor in the tungsten business; Ballin has agreed to be the frontman for the lucrative tungsten mining interests owned by Nazi Germans for the duration of the war.

Once the war is over, the tense master-servant bromance between Ballin and Johnny is ended (or perhaps brought to new anguished, tragic heights) when Ballin comes back from a business trip with his new whirlwind-romance bride: the staggeringly sexy and insolent Gilda, an American singer and dancer played by Hayworth, her face always lit and shot with a kind of radioactive glow of romance and danger as she flirts outrageously with almost every man she meets.

Ballin is infatuated with Gilda but senses something (like the cinema audience itself) the moment Johnny and Gilda set eyes on each other. Of course: these two already know each other. They had a romance. It ended badly. Nothing needs to be said, and Ballin’s pride will not allow him to admit what he realises: that he has been retrospectively cuckolded by his underling. Firing Johnny or divorcing Gilda would be an unthinkable admission of defeat. So the trio have to continue together, each existentially humiliated by what they know about the other two, stewing and simmering as their violent rage and despair bubble to the surface.

This emotional triangle is embedded in a thorny tale of corruption and corporate malfeasance—the complexity of the story is also part of the noir experience, although Gilda isn’t as confusing and head-spinning as Howard Hawks’s The Big Sleep (1946) or Orson Welles’s The Lady from Shanghai (1947). The intricacy, even the out-and-out inexplicability of the traditional noir plot is an effect. Like the shadows, like the looming faces, like the cynical bleakness: it is part of the noir strategy of disorientation. It is literally noir: you can lose yourself in the dark.

Hayworth is a sensational presence in the movie—her charisma, sexuality, and star quality shrewdly nurtured by Columbia studio boss Harry Cohn and the movie’s formidable screenwriter-turned-producer Virginia Van Upp. The two male leads can almost be nothing more than courtiers, at some level jealous of Gilda and resentful of the way she has destroyed their relationship. Ballin has said that he, Johnny, and the sword-stick were the real trio of friends, now supplanted by this new trio. But any Freudian theories about the phallic nature of the stick and the supposed unconscious repressed gay relationship of Johnny and Ballin are complicated when, over drinks one night at the casino, they decide that the sword-stick is a “her” and not a “him”. And all the time, the complex emotion of hate throbs like an engine under everything: partly genuine and partly displacement activity. As Gilda says: “Hate is a very exciting emotion. Haven’t you noticed? I hate you too, Johnny. I hate you so much I think I’m going to die from it… Darling!” In Gilda, hate is the drug. Or the addictive methadone substitute for love.

Gilda itself, for all its amazing musical setpieces, is a film that switches off the sound and lets you see the human figures writhing and quivering

Peter Bradshaw

in their unhappiness.

Gilda’s sexuality is transgressive, destructive, and explosive. Her mesmeric song Put the Blame on Mame is initially sung by her at five in the morning, with her own strumming guitar accompaniment to an audience of one: the washroom attendant Uncle Pio (Steven Geray) and later, in spectacular public style, to tuxed crowds, accompanied by a kind of attempted mock striptease that almost causes a riot. The song cynically suggests that a number of famous natural and human disasters can be attributed to this fatale woman called Mame: an entirely appropriate song for the bombshell whose name and movie image was used (to Hayworth’s own dismay) by besotted GIs to christen the Bikini Atoll nuclear bomb in 1946.

It is a film that teases and plays with the idea of meaning; it flirts with its own semiotics. Gilda is superstitious. She ponders signs and is forever asking what something can possibly mean. She has difficulty with zippers. What can that mean? It is raining on the day of her second wedding, to Johnny. What can that mean? Audiences, critics, and deconstructionists rush forward with interpretative excitement about unclothing, revelation, and doom.

This was the classic noir text, and the obvious complicated debt to Michael Curtiz’s wartime classic Casablanca (1942) hardly needs to be pointed out. It’s almost an anti-Casablanca, and the huge difference is that Casablanca offered us a huge flashback, underscoring the romantic good faith of Rick and Ilsa’s war-torn romance in Paris. But there is no flashback in Gilda. We don’t see how Johnny and Gilda met, how they broke up. It is all cynically taken as read. They had a fling during the war and dredging it up now is embarrassing. There is nothing to explain.

The noir movie, perhaps like any movie at all, is a movie about faces: Johnny’s face and Ballin’s face are closed: they have something in reserve. The card-cheat Johnny and businessman Ballin (preparing to welch on his deal with the Nazis) clearly have secrets. Not Gilda, whose face is dazzlingly, radiantly open and beautiful and seductive, even as she is eaten up inside with pain.

What an amazing film it is. My favourite moment is when Ballin, in his office overlooking the casino and dance floor, can switch on and off a microphone that can suddenly make the throng of wildly gyrating revellers below him weirdly silent. Nietzsche is often apocryphally quoted to the effect that dancers are thought to be insane by those who cannot hear the music. Gilda itself, for all its amazing musical setpieces, is a film that switches off the sound and lets you see the human figures writhing and quivering in their unhappiness.

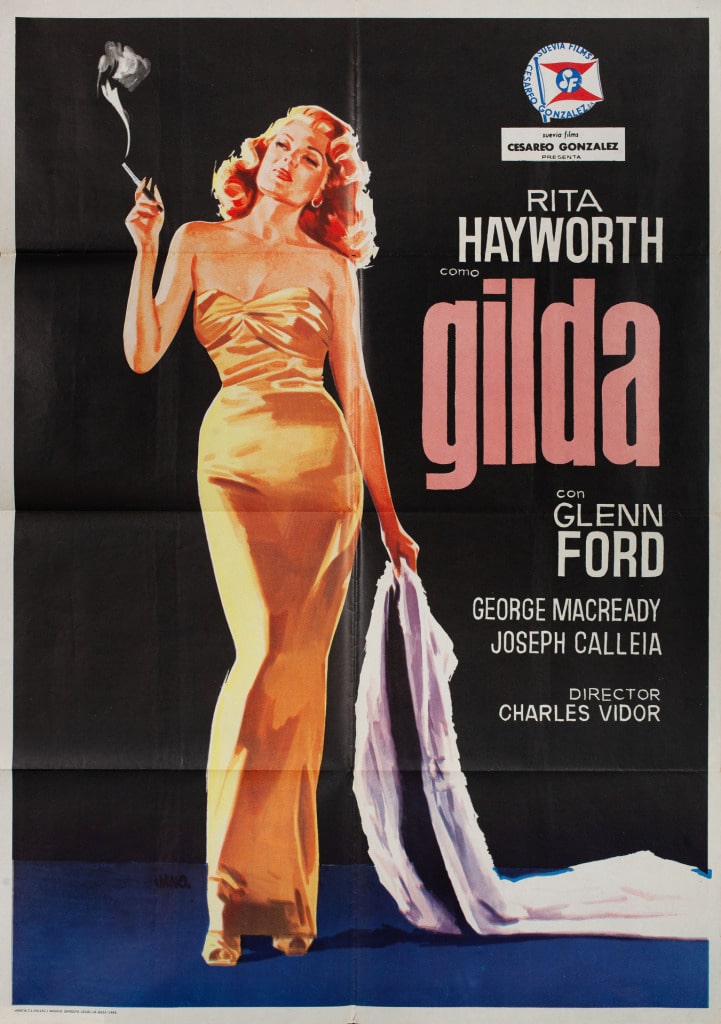

Main image: Rita Hayworth and Joseph Calleia in Gilda (1946). By Charles Vidor.