Panic on the streets of east London. It’s a rainy day at a Whitechapel snooker lounge and Ray Winstone is early, too early, and I’m haplessly trying to find a way to organise our special shoot before we settle down to chat.

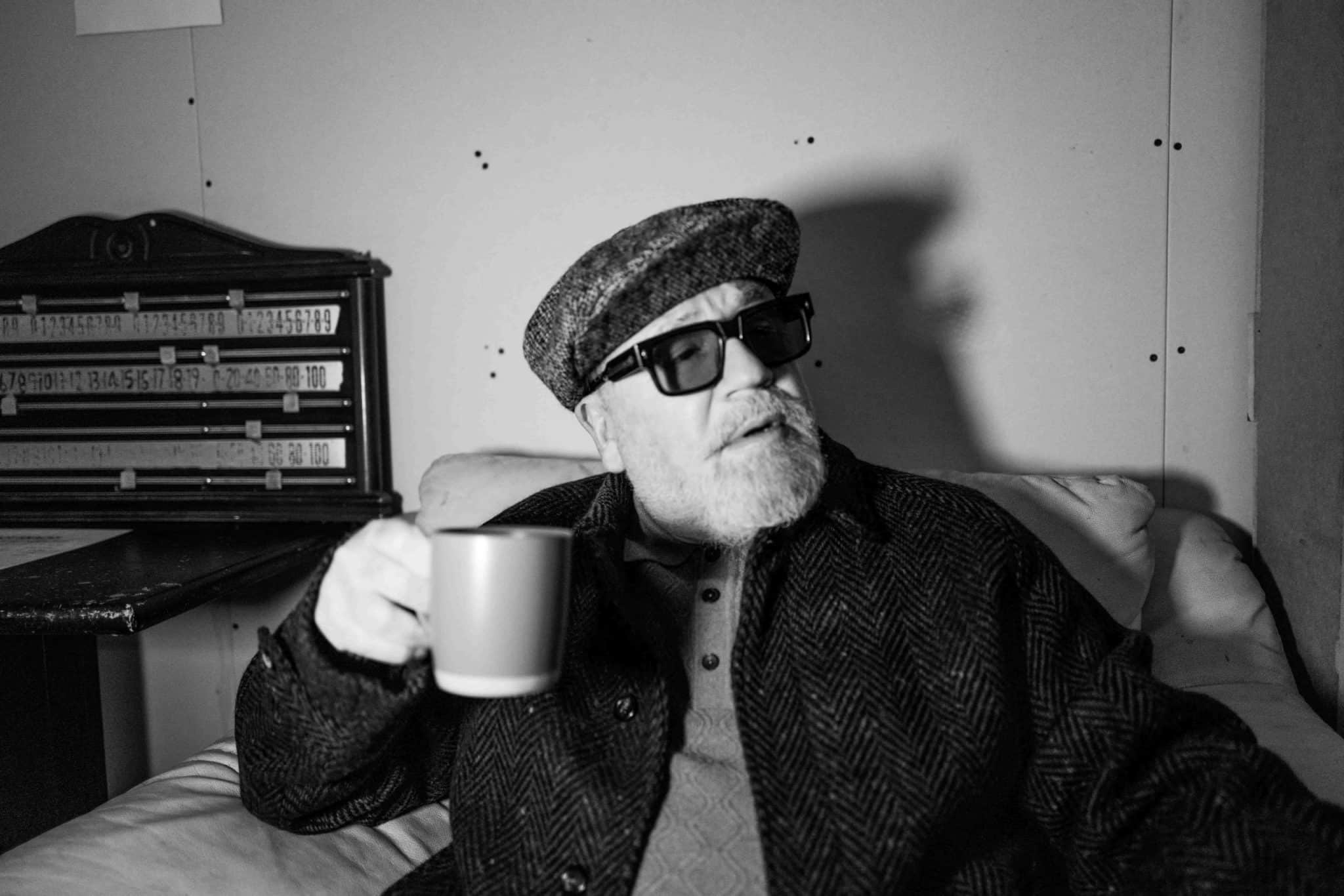

“Right, before we do anything,” Winstone bellows as he strolls in, all jovial with his thick cockney accent, sporting a baker cap and tinted glasses, “shall we all have a cup of tea?” He’s like a favourite uncle who brings order to the whole scenario, filling us all with relief as he strolls from one workstation (see: snooker table) to the other—between the stylist, Tom, his make-up artist, and our savvy photographer, Luke—aware of what must be done to finish the job. It’s Ray Winstone, after all, an icon of British cinema; a man whose long career has spanned some of the greatest filmmakers of their generation, including recent Oscar winner Jonathan Glazer in Sexy Beast (2000) and Martin Scorsese with The Departed (2006) and The Irishman (2019). He knows what he’s doing.

As he leans over the snooker tables, he can’t help but recount stories from his youth. “Me and my buddy used to hang out right across the street,” he smiles, as he falls into a short anecdote that I cannot remember. It’s a common theme of our time together and we all listen attentively. He can really hold the room, and each story is bookended with Winstone nostalgically sighing “Those were the days.” It’s natural to take a trip down memory lane when you return to the East End. I know because I was also born in the area; my parents were raised close to where we are playing (or feigning to play) snooker. For London’s emigré cockneys, Winstone is our Robert De Niro. With every crook, hustler, geezer, lothario, Arthur Daley-type chancer, or rogue he has played, the colourful characters of the East End are brought authentically to life in the way that we know them. “I like that,” he grins, taking a pensive puff of his vape pen. “Robert De Niro. But I also like ‘Cockney Clooney’.”

When shooting is wrapped up, we sit in a small back room that the proprietor explains is being newly renovated into a lounge area. In the pictures, it was finished. Today, the floor has been ripped out, the leather booths are soiled, the lights have a shadowy purple hookah bar dim, and we’re interrupted by drilling and the sound of chatter from the other visitors, but Winstone doesn’t mind much; you get the impression he enjoys the makeshift nature of it all. He has been surrounded by the notorious denizens of the East End since his infancy and holds on to the unpretentiousness that other A-list actors might well express in the situation. He describes when one of the famous Kray twin gangsters visited his father and what happened when a baby Ray “pissed all over” the villain’s brand-new coat. “The room was silent,” he says, “then Reggie [Kray] laughed, and so everyone else knew it was all right to laugh too!”

I wonder if he was also a bad sort as a kid. “Not really, no,” he explains matter-of-factly. “Just mischief.” Winstone grew up in post-war London, where his playground was the scattered rubble from bombed-out buildings. “We would put bricks in the middle of the road when the milkman drove down in his cart. We were horrible! But what happy memories,” he says. As a teenager, he had a promising amateur boxing career (80 wins out of 88 bouts) at the famous Repton Amateur Boxing Club in Bethnal Green, which he credits with “showing me discipline. Theatre and boxing are the same,” he says. “It’s a group effort. But the difference is that if you make a mistake in boxing, you’ll get smacked in the face.”

So how do you go from the dusty world of boxing gyms to the stage? When he started acting, he tells me, his parents were relieved that he would be kept off the streets; away from the Essex nightclubs he would frequent with his underage pals (many of whom are still his closest friends). But, like so many of the unforeseen transformations in a young man’s life, it started with a girl.

“I fell into acting. There was a pretty girl taking part in the school play and so I decided to audition,” he explains. “It was at a time when kids where I grew up didn’t become actors, so you have to understand, I wasn’t sure where I was going with it.” Even after so many decades in the business, being from a working-class background has provided Winstone a feeling of imposter syndrome, he admits. It’s something I understand only too well, and when I agree with his sentiments and overshare too much about my own life, he starts offering me encouragement. It’s good old uncle Ray again. “Don’t worry about it, kid,” he says to me. There’s a pause for a moment. “If you don’t have that [chip on your shoulder] then what else do you have to make you go on? I thought that nobody would accept me in this game. That’s our East End thing. It’s inverted snobbery.” He recalls a ridiculous event at the LAMDA drama school in his early days, when, during an examination, he recited Julius Caesar as “a bloke in a pub” and received a grade zero from the examiners. “Not even a point for inventiveness,” he laughs. “I could’ve packed the acting in there and then, but I thought, ‘Fuck you, I’m not doing the same as everyone else.’ It motivated me more.” You can’t help but think that this kind of performance would be hailed today as a subversion of the classics through the voice of the working class (ironically, he played King Duncan in a Macbeth adaptation called Macbeth on the Estate in 1997 opposite David Harewood). But not in the 1970s. To understand Winstone, you need to understand that it wasn’t always easy on the way up.

He chanced on some unexpected hits and notable mentors early on. While working in the wardrobe department at the National Theatre, Winstone was able to meet and observe his hero Albert Finney during an adaptation of Hamlet. Then there was the BBC prison drama Scum in 1979. “It so happened that while I was at the National Theatre, Alan Clarke was looking to star in the film.” Initially, the character of Carlin was written as a Glaswegian—not a cockney. “I was told I got the part because of the way I walked through the corridor,” he says, “because of my boxing posture.” Winstone speaks about Clarke with a sense of reverence and gratitude—even at 67, you never forget your mentors or how they lifted you from obscurity. “I was lucky to have him there to install the thoughts now forever lodged at the back of my mind, and which I’ve carried all throughout my career,” he says. I’m reminded of Clarke’s reputation for discovering great young actors: the likes of Tim Roth and Gary Oldman (another cockney, who would cast Winstone in his excellent Nil by Mouth (1997)) came from the Clarke school of television drama. Scum was a brutal, deeply sinister borstal thriller; part of a new social realist movement in British film, and after starring in Quadrophenia and That Summer! the same year, Winstone suddenly shot to fame as its emerging poster child. In 1979, he was nominated by the BAFTA Awards for Best Newcomer. He was just 22.

“Look, it’s easy to go off the rails,” he admits, when I ask if he struggled with his early fame. “I’m sure it happened to me. I didn’t have much of a clue what I was doing and it was all a bit of a laugh.” How can a young lad from Plaistow be expected to make the right decisions after such sudden success? He followed his dazzling start with a series of television appearances and theatre work, but he admits he was no lover of the theatre. Film was the real goal… until it wasn’t. “One moment you’re Johnny Big Bollocks and then there’s nothing,” he tells me. “After making this film in Vancouver [Ladies and Gentlemen, The Fabulous Stains (1982)] I returned home and the phone stopped ringing. I had to reinvent myself. It’s something I’ve done four or five times in my career.”

Winstone’s next film would come in 1989, as investigative reporter Tank Malling in Beyond Soho (one year after he declared bankruptcy). After impressing in Oldman’s Nil by Mouth, he reinvented himself as the quintessential British hard man and has been a prolific on-screen presence ever since—sometimes starring in up to four projects per year.

But I wonder if he’s jaded by being profiled as the hard man. Winstone is a classically trained actor, who at some point might have envisaged himself in a wider range of roles; his favourite performance is still his portrayal of King Henry VIII in a 2003 TV serial of the same name. Bringing the poet William Blake to the screen has long been a dream of his too. “I love Blake. I wanted to play him years ago,” he says. “No one has ever got to the bottom of him. But I’d like to make it a horror film—there was something strange about him. I’ve got a meeting next week with someone about it.” Sam Taylor-Johnson, he tells me, gave him some pretty interesting visual ideas that he hasn’t been able to shake. “She’s very clever, but I’m too old to be cast as Blake now,” he admits.

Even as he enters the elder statesman phase of his life, it’s the hard man roles that continue to come in the most. Winstone has perfected it to an art form (inspiring the burliest of silver-screen geezers ever since) but with so many other projects in the back of his mind, I ask if it ever feels a bit forced on him. “They still come in and it’s fine,” he says. “You have to find a different way of playing them each time to keep it interesting.” He mentions The Gentlemen, a new Netflix series directed by Guy Ritchie in which he plays a mob kingpin: “I wouldn’t have understood Guy’s style when I was younger. It’s not necessarily realism,” he says, on Ritchie’s pulpy, tweed-and-sawn-off version of the criminal underworld, “so I approached it as a different way of portraying that type of character.”

It might surprise audiences to know that there is, if you’re curious enough (and if you can find it), a film where Winstone was cast as the romantic lead. When I mention 1999’s Fanny and Elvis—a comedy about a couple who fall in love after a car accident—a broad smile appears on his face, as though I’ve unlocked an displaced memory. “That was a great change. I loved it,” he says. But when I ask him whether he would’ve wanted to do more love stories, he becomes serious. His career has been a series of romantic portrayals, he tells me—including crime thriller Sexy Beast. “You always start with a love story, otherwise you’ve got nowhere to go. Sexy Beast is about the love of a woman [Winstone’s on-screen wife], and the lengths he goes to protect her,” he explains. “That’s what is behind the film and the violence. Same as in 44 Inch Chest (2009). He loves a woman so much it makes him a possessive, jealous monster. It’s a fine line but these thrillers must start with love and reach the other [darker] end. If it’s about love, you have to work towards it. You need to know the difference. I do, anyway.”

Sexy Beast was a turning point in Winstone’s career. The image of him lying on a sunbed in Spain, oiled and skin-seared in tight Speedo briefs, has become one of the most iconic in British cinema. It was Glazer’s first feature film, and Winstone knew there was something special about him from the start: “I like working with first-time directors because they don’t know the rules, so they’re more likely to break them,” he says. “Jonathan was especially raw working with actors. When we started on Sexy Beast, he learned quickly because he’s so bright and talented,” he adds. “The tragic thing about Jon for us as moviegoers is that he doesn’t make many films. He likes to be there the entire way through production, and so that can take five to 10 years.”

Although he’s built a career playing characters who can rip your head off, he’s still sensitive to criticism. Even after so many years in the business and so many accolades, a big spotlight still equals a bigger sense of scrutiny. “If someone writes, ‘Oh, he was shit’ in this or that performance, you can show it doesn’t hurt but it does,” he says. “Look, it’s fine if it’s about the performance, but when it gets personal that’s when you have a problem—or I suppose they have a problem.” He is a friend of comedian Dawn French, and mentions a review of her work he read years ago that made him want to confront the journalist: “It upset me. He needed to be dragged out. What a horrible man. It was all about her and not the performance. That’s not his job.”

For such a prolific actor, it’s unlikely every film he works on will have the same critical acclaim as The Departed or Sexy Beast. But at this stage in Winstone’s career, that’s OK. He explains a recent decision to work with Juan Carlos Fresnadillo on the 2024 Netflix dark fantasy Damsel (as well as why he’s been in more family-friendly films like Indiana Jones over the past few years). Winstone enjoyed being directed by Fresnadillo and, just as importantly, “It’s nice to make something the grandkids can watch,” he laughs. “But also, you’ve got to pay the bills. It doesn’t matter how well everything is going.” His prolific career is a consequence of “hard graft” learned from his grandparents—as well as the very relatable East End fear of what might happen if you stop working. The result is a long mishmash filmography of big Hollywood blockbusters, independent movies, and various TV shows in between—some great, some not so great. “I look back at my family and they’re straight out of the poorhouse,” he explains. “Not that it’s got anything to do with it, but they survived. That adds a sense of responsibility you feel to your family. You are the caveman. You’re the one that goes out and batters prehistoric monsters to bring home and cook. That’s still in me. If we’ve got a problem, I’ll go to work.”

There have been high-profile projects he has rejected but every decision is made for a good reason, he adds. “Don’t get me wrong, I love Harry Potter, but I turned it down because I didn’t want to do another eight hours in the prosthetics chair,” he says. Winstone also recalls declining the HBO series The Wire because he didn’t want to raise his young children in the United States. He remains a family man—a proud dad who can’t wait to talk about his child’s proficiency at Spanish or his daughter Jaime following in his footsteps as an actor. “But I weren’t having them become American kids. They’re Londoners.”

Surely he must find some downtime, I ask him. In between all of the shooting schedules and press tours, the actor loves nothing more than getting into the car at his Essex home around four in the morning and taking off to the continent. He vividly describes the road between Calais and Paris, the long stretch of highway that leads you to the French Riviera and some of the nameless towns in between. I suddenly get this image of being stuck in traffic outside the Eurostar at dawn and locking eyes with Ray Winstone on the way to Dover. He wasn’t always interested in travel, he admits. Being dragged from his London bubble to shoot in faraway lands sparked a curiosity for other cultures, and the way he describes each of these places could be recited from a written travelogue (he is, I remember later, a classically trained actor, after all). In 2020, he filmed a Bourdain-esque travel docu-series on Sicily in Italy, one of his favourite countries on earth. “I stopped in Pisa last time and the tower is the most incredible structure you’ll ever see,” he tells me. “The detail of the stone, it’s fucking stunning. If I was 25, I would’ve been drunk, staring at it thinking, ‘that looks pretty straight to me’.”

Those heady days as a man about town no longer define him. He has no regrets, he admits—none that are clear enough to him at that moment. His mum died at 52, he says, and he still wishes she had met her grandchildren. “That’s the most incredible event of my life. I was only 28 years old.” But when it comes to a career, “if you change one thing you wouldn’t end up where you are,” he says. “Look, I’ve been skinned a few times and I’ll be skinned again. If someone ain’t loyal to you, fuck ‘em. And the closer they are, the harder it is to forgive. But the principles I’ve always tried to live by are honesty and integrity.” Ray Winstone, hard man of British cinema, proper family man, and everyone’s honorary cockney uncle, smiles and lowers his voice. “Not that I’ve always met these principles.”