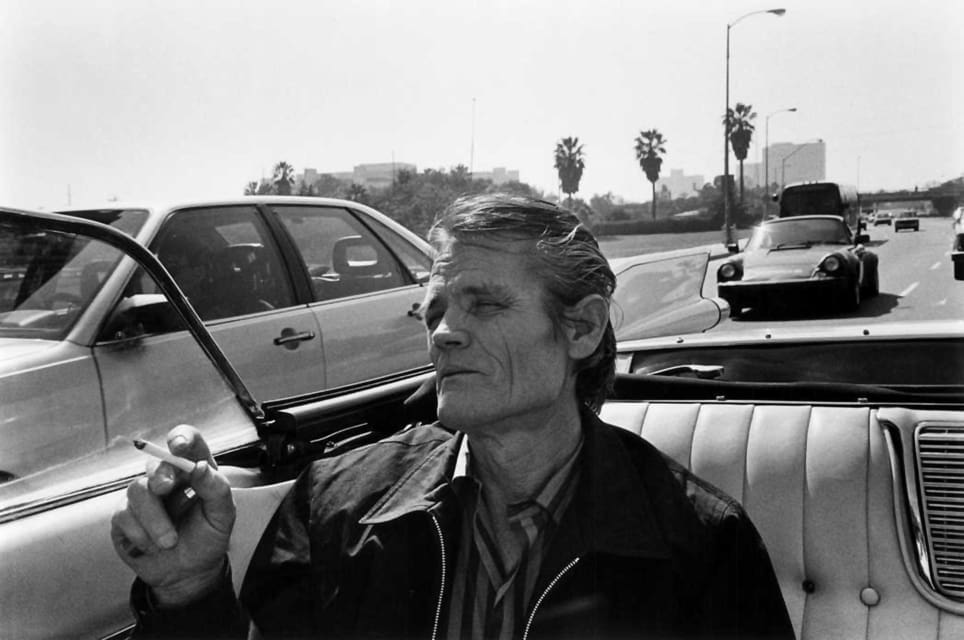

“Everybody’s got a story about Chet Baker” you hear someone mumble in Let’s Get Lost, Director Brian Weber’s essential portrait of the great American jazz musician. The film is a collection of black and white snapshots of his friends and family, ex-lovers and the man himself during the final years of his life. You’ll see Baker cruising the streets of LA in the back of a convertible, cooly pulling his wife in for a kiss; in the studio laying down smoky vocals, trumpet in hand, and riding around in bumper cars with his friends, a giant toothless grin on his face.

Let’s Get Lost premiered at the Toronto Film Festival in September of 1988, just over four months after Baker was found dead on the street, having fallen from his hotel balcony in Amsterdam. His death, though ruled an accident, has been heavily speculated over the years. Some say it was murder; a drug dealer from whom Baker had stolen getting his own back. It’s a dark thought, but an oddly fitting mystery for a man who lived life as an enigma. To many, he was the Prince of Cool—the “James Dean” of Jazz, a troubled but sensitive loverboy—but the mythology he carried remains labyrinthian.

The mythos starts with the music, of course, and it was there that Baker gave the most of himself. There’s a reason why Chet Baker appeals to both the lovers and the broken-hearted in equal fashion: because when the needle drops, time around you dilutes, and suddenly you’re a wayfarer courting distant memories. He had the ability to be at once a slow dance between sweethearts and a murmur of wind haunting an inhospitable midnight walk. He had the blues about him, and every note he played or sang carried the blues on its back like an airborne disease. What makes a “good” voice?Technique? Range? For Chet, it was pain that made him—and not many did pain like him. It made him a great musician, and it made him an even better addict. “There’s something lonely and detached about his music”, said Ethan Hawke, in a 2015 interview. “Chet Baker didn’t sing well, but he sings like a memory of somebody singing well.”

When Hawke played Chet Baker in the semi-factual, semi-fictional biopic Born To Be Blue (dir. Robert Budreau), the nature of the musician’s drug use and creativity asked a question that, if you’re an artist, you might have pondered yourself at one time or another: is suffering synonymous with art? Chet seemed to live resoundingly as if the answer was yes. He wasn’t quite a drugstore cowboy, but he was pretty damn close; for a long time his life was a revolving door of prison cells. Rikers Island: four months. San Giorgio prison, Lucca, Italy: a year and seven months. The middle years of Chet’s career were as off the rails as they come, which made his comeback at the tail end of his life even more of a sight to behold. These interim years were defined by his heroin addiction, which he claims started in 1957, and he lived for the high like he lived for the music.

And both ran parallel with each other. He composed avidly during his sentences, and the legend goes that prisoners would line the walls adjacent to his prison cell to hear the sounds of his trumpet escaping through the barred windows into the open Italian air. But his stints in prison, usually on drug charges, led to the quality of his work to decline, and he was forced into early retirement after a severe beating in 1966 ruined his embouchure. The way Baker always told it, he lost his teeth after an acquaintance and his cronies robbed him for drugs, cutting him up and busting his teeth in the process (for perspective: a trumpet player playing with busted teeth is like a keys musician playing without hands.) “My mouth had been damaged to the point where the best thing to do was to take ‘em all out.” Chet says, in Let’s Get Lost. “I never had good teeth anyway.”

What followed were the lost years of Chet Baker. He worked at a gas station for three years. It begs to be believed—one of the greatest Jazz musicians of all time, pumping gas from seven in the morning to eleven at night. He and his family moved in with his mother in San Jose, where he relied on welfare. He was arrested again, this time for forging drug prescriptions, released a few more unsuccessful records such as Blood, Chet and Tears (1970), a collection of uninspired bops with none of the glorious yearning that was all but trademarked by Baker—before resigning himself from music for a time. Yet even at his lowest, his peers ,the black Jazz artists that pioneered the genre, kept a level of respect reserved for Chet. “It was three years before I played again for a New York audience…it was Dizzy [Gillespie] that got me the job. He made a phone call in New York, came back a few minutes later and told me he got me three weeks of work at the Half Note.”

Born To Be Blue imagines a reality where Baker accepted producer Dino de Laurentiis’ offer to play himself in a movie about his career. It’s a peek into a parallel life he could have lived, though his nature in the film remains true to the man we knew he was: smooth, erratic, lonely, addicted, charming, destructive. By deviating so far from the gospel of Baker’s life it ironically ends up getting to the core of who he was more accurately than the average biopic. Budreau and Hawke approach his journey as if it was jazz itself: a variation of a single theme, drawing on Baker’s mythology and liberating themselves artistically in the process. “If you read a lot of Chet Baker interviews, he can’t keep the same story about how he loses his teeth”, says Budreau. “In one interview he says one thing, in another interview ten years later he says something else. He’s not even consistent with his own mythology. [Born To Be Blue] is about trying to capture [his] spirit.”

At the end of Born To Be Blue, his wife leaves a newly relapsed Chet after seeing him stumble out onto the stage, clearly intoxicated. He plays just as intoxicatingly. The great Chet Baker curse, according to him. Though his wife in the movie, played by Carmen Ejogo, was conceived by Budreau as a composite of various different women in his life, it’s a hint that maybe the best way to try and understand the beating heart of the musician is through those that cared for him.

In Let’s Get Lost, Diane Vavra, Chet’s partner and a musician in her own right, likens meeting Baker for the first time to catching a glimpse of a Greek god. “The first minute I saw him I was in love with him,” she remembers. Like the gods, he could be as manipulative as he could be passionate, and Diane relates experiences with both. When they would split up, she says, he became angry, and screamed and threw things like a child. After one break up, she visited him in San Francisco, where he was playing a gig, and found him indifferent towards her. “I embraced him and broke down, and I said ‘Chet, how do you stop loving somebody?’ and I kept saying it over and over again.” She asked to meet him the next day, to which he agreed. “I waited six hours,” she says, through tears. “He never showed up.” On wax, Baker projected a hopeless romantic, and the girls loved him for it, but the love he held inside him was far more complex, and the girls who knew those complexities had no choice but to love him, still. “You can’t rely on Chet, and if you know that, then you can pull through.”

Chet had a trickster quality about him, and when he wasn’t conning for a score he was laying the breadcrumbs of his own legend mischievously. Most would agree that Let’s Get Lost is quintessential viewing for any jazz lover (or cinema lover for that fact), but the nature of Chet was such that even a documentary as intimate as this couldn’t completely peel back all the layers of his soul. The ultimate unreliable narrator and the king of the misdirect, there are rumours that after speaking with Weber for hours Chet would call a friend and gleefully brag that he had taken the fashion photographer on a wild goose chase. Baker made a final attempt at a comeback in 1973. But could he still play? That was the question on everyone’s lips. Against all odds, he could. It turns out that Chet had relearned how to use his embouchure through his dentures, a herculean task, as any trumpeter will tell you. Hawke says something interesting about Baker: “There’s a weird thing about drug abuse, that you think it means that they don’t care about life…I thought that because Chet was a drug addict that he didn’t care, but he cared immensely. The only time he really got sober in his life was to learn the trumpet. There’s such a duality to that kind of person.”

Duality is the right word. It’s what made Baker such an exhilarating presence in and outside of music. And it’s what kept people interested until the very end. In the last few years of his life, he released some of the best music of his career. He recorded the legendary live album Chet Baker in Tokyo, played on his terms in tightly-huddled jazz bars. He collaborated with musicians he admired, like Eric Costello, Philip Catherine and Michel Graillier. He enjoyed a multi-act career yet never learnt how to read a note of sheet music. His legacy still touches the present day: artists like Mitski and Laufey and hundreds of others who have captured the acute yearning that he perfected on his records. You see his lineage everywhere: those who ache like Chet.

The last public interview with Chet was recorded just over four months before his death in 1988. His face looks stylishly worn, tough as leather; a far cry from the sharp cheekbones, defined jawline and boyish smirk you might remember from the cover of Chet Baker Sings. What remained, though, was the talent itself. “I hadn’t seen Chet in 20 years,” photographer William Claxton says in Let’s Get Lost. “I didn’t think it was the same person, he had changed so much. It made me sad, actually. But the moment he talked and sang and played his trumpet, it all came back, this wonderful image again.” The same flair is alive in this final interview, which sees Chet perform a few tunes in a cosy, unassuming old cafe in Amsterdam and reminisce on his long career. He relates the first time he and Charlie Parker played with each other, at a last-minute audition in a pitch black room at the Tiffany Club in LA that led to a stunned Parker sending all forty other trumpet players home and hiring Baker on the spot. “When he went back to New York he told Dizzy [Gillespie], Miles [Davis], Lee Morgan and all those cats…’you cats better look out, there’s a little white cat out in California that’s gonna eat you up!'” Everybody has a story about Chet Baker, but no one could tell it with quite the same finesse that he could.