Early figurations of lesbian characters in cinema generally fall into two categories. They either depict women doomed to be forever lonely, or present these characters as overly sexualised figures, seducing her heterosexual counterpart; neither of which accurately illustrates the lesbian experience. In addition, these on-screen depictions often carry a lack of representation behind the camera, as many of the films centred around queer female characters, have been directed by men. Historically sapphic scenes directed through the male gaze were often heavily eroticised, such as David Lynch’s unnerving thriller Mulholland Drive and the neo-noir Basic Instinct, directed by Paul Verhoeven. More recently, Blue is the Warmest Colour directed by Abdellatif Kechiche, winner of the Palme d’Or in 2013 or The Handmaiden, Park Chan-wook’s critically acclaimed masterpiece and another Cannes contender, followed a similar trend. Although these are exquisitely crafted pieces of cinema, showing these queer characters through a male lens can distort viewers’ perception of the lesbian experience.

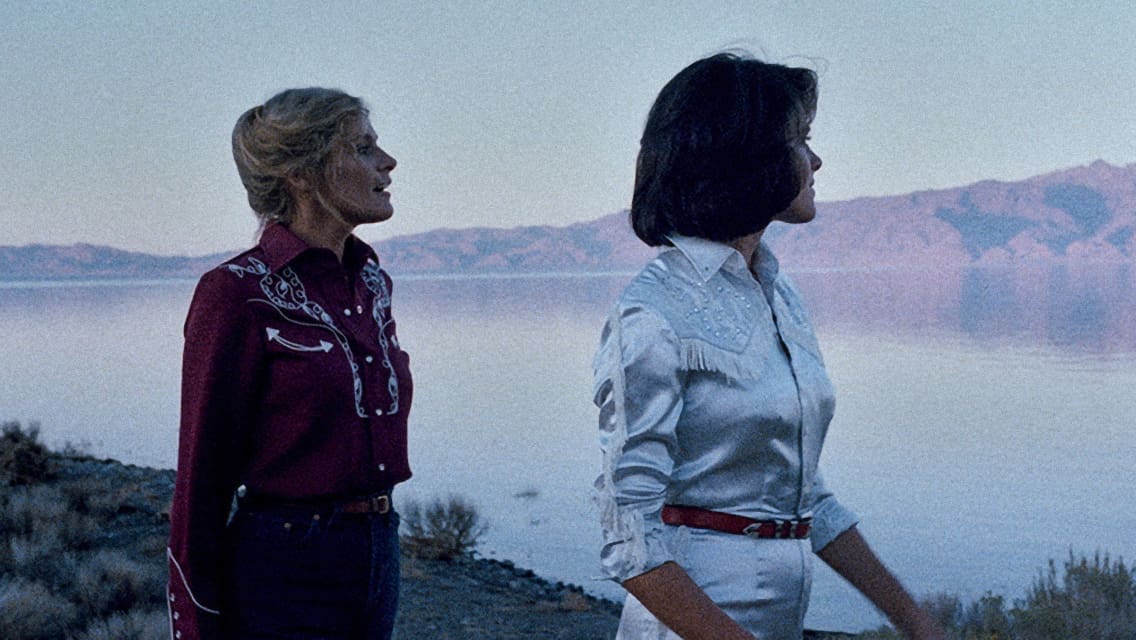

Yet when examining more realistic pieces of cinema which appropriately tackle queer characters and relationships, there are luckily several examples that explore these themes with a more conscientious approach. One of the most influential films of this genre is Desert Hearts. Frequently hailed as a pioneering feature, it premiered in 1985, when realistic films centering around the realistic queer experience were few and far between. With nearly six years in development, Desert Hearts was groundbreaking not just in its subject matter but for the film’s female lead, cast, and crew. Directed and produced by Donna Deitch (who also co-wrote the film with Natalie Cooper), Desert Hearts tells the story of Vivian Bell (Helen Shaver) a prim New York English professor who travels to Reno to finalise her divorce, following a separation from her husband. Shortly after her arrival, on her way to the ranch where she’s staying, she sees through a cloud of desert sand a 1957 Ford Fairlane convertible, driven by Cay Rivvers, a younger free-spirited sculptor (Patricia Charbonneau). As the story progresses the two slowly fall in love, leading to a sexual awakening in Vivian, whilst also motivating Cay’s geographical exploration.

A review on its release from the Chicago Tribune compares Desert Hearts to traditional Hollywood romance films, unheard of for sapphic films of the time; and credits it for finally achieving ‘the de-sensationalising of lesbianism.’ The sweet romantic storyline, threaded throughout the film was revolutionary at the time, as it follows traditional cinematic tropes, recognisable to audiences. The two characters make an unlikely couple, from vastly different background, with Cay in jean shorts and cowboy boots, while Vivian wears proper suits and pearls, fitting for a New York professor. Yet the couple’s slow burning tension, with sideway glances and the passionate performances by Shaver and Charbonneau creates an archetypal love story. Even the film’s ending is reminiscent of the happy endings in classic romantic films, as Vivian, now divorcee, heads back to New York and begs Cay to go with her. Although Cay initially resists, she agrees to ride with her to the next stop and taking Vivian’s hand climbs on to the train, allows the audience to speculate what happens next— a familiar and hopeful finale.

The film proves that allowing for accurate representation of the lesbian experience on screen can lead to more engaging storytelling. By focusing on the sapphic love story and relationship between the two central characters, rather than indulging in the trauma of gay women living in a puritanical era, Deitch allows the film to feel more familiar to its audience. This is something which the film has in common with the novel it’s based on. Desert of the Heart by Jane Rule is a book which was hindered in publication due to its lack of sexual sensationalism. Set in 1959, the film is a period piece, using the era in which it takes place as a backdrop to highlight the contradictory upbringings and attitudes of the two protagonists. Vivian’s East Coast origins and Cay’s roots in Nevada are set against the chosen year, the final period of the Eisenhower administration just before John F. Kennedy was elected to office. The change in the political landscape mirrors Vivian’s change in circumstance, and the irony of her finding sexual freedom only after leaving a large seemingly bohemian metropolitan city for the desert. One of the main themes is the emphasis on space, a concept which is even commented on by Vivian in the film’s first few minutes who states, “I don’t know what to do with all this space.” Deitch allows a milieu, often shown in Westerns through the male perspective, to be embraced by the female protagonist who equally indulges in the setting. This abundance of space is brilliantly shown through the film’s cinematography, as Robert Elswit’s lens lingers on the desert’s vast landscapes to create mesmerising imagery, consumed by the audience as well as the film’s characters.

Desert Hearts is the product of Donna Deitch’s determination. Pivoting from documentaries to features, the director wanted to produce a queer film that would crossover into mainstream audiences, which explains why the film is reminiscent of the classic love stories. On its release it played at respected festivals, including Toronto and U.S. Film Festival (which later became Sundance), and grossed over $2 million in its theatrical release, a significant achievement for a female-directed independent film. Yet despite the film’s critical acclaim, it failed to produce the impact hoped for by the filmmaker and the LGBTQI+ community. Feminist film theorist Jackie Stacey, for example, expressed surprise that Desert Hearts didn’t create a surge in more popular realistic lesbian romance movies. However, the film has since proven to be a prominent and innovative piece of cinema, appreciated decades later and reaching a cult status amongst today’s youth audiences. The film was one of the several which inspired the singer-songwriter Mitski’s latest album, The Land Is Inhospitable and So Are We; leading to her showing the film as a double feature with her album release.

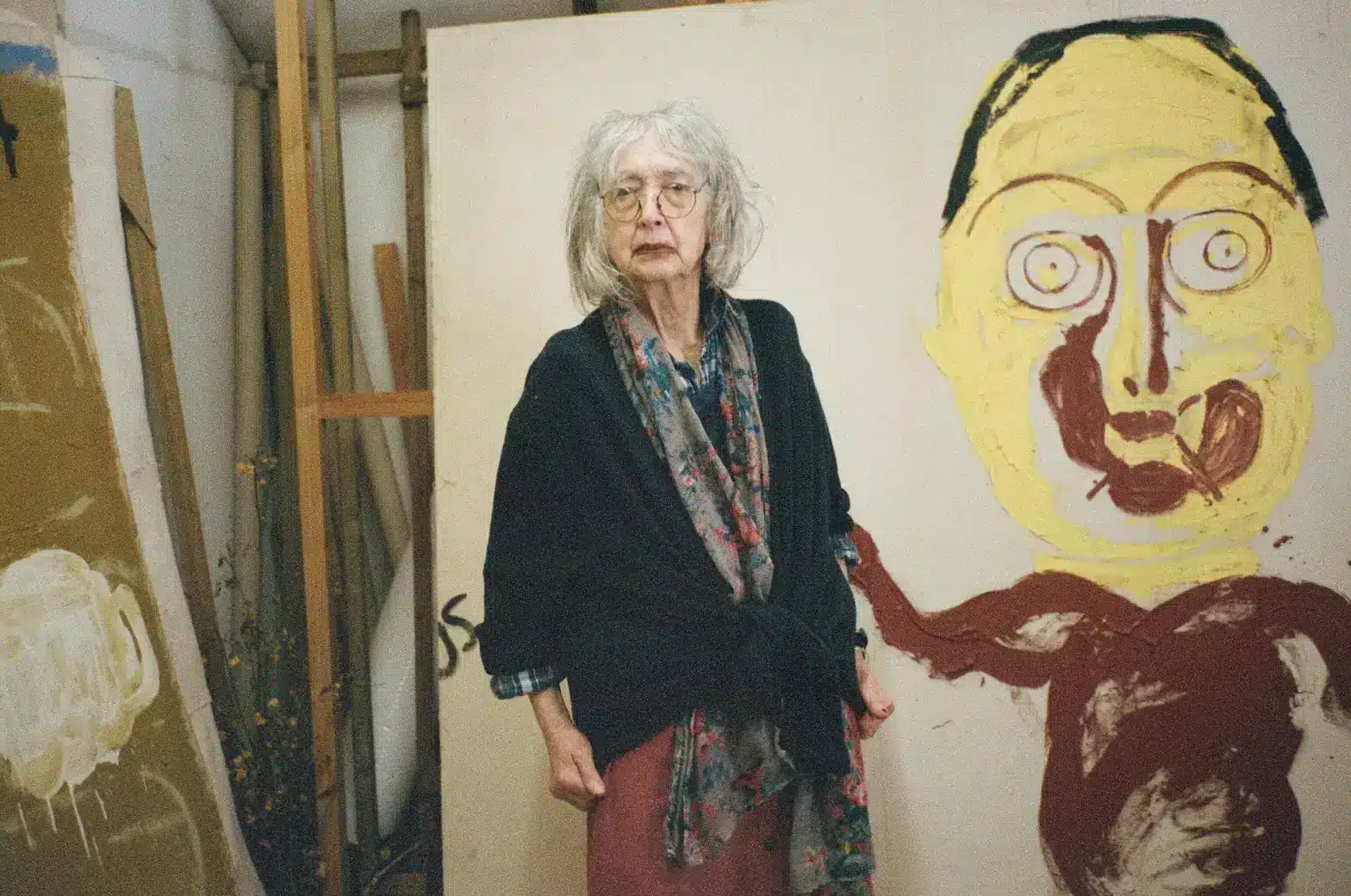

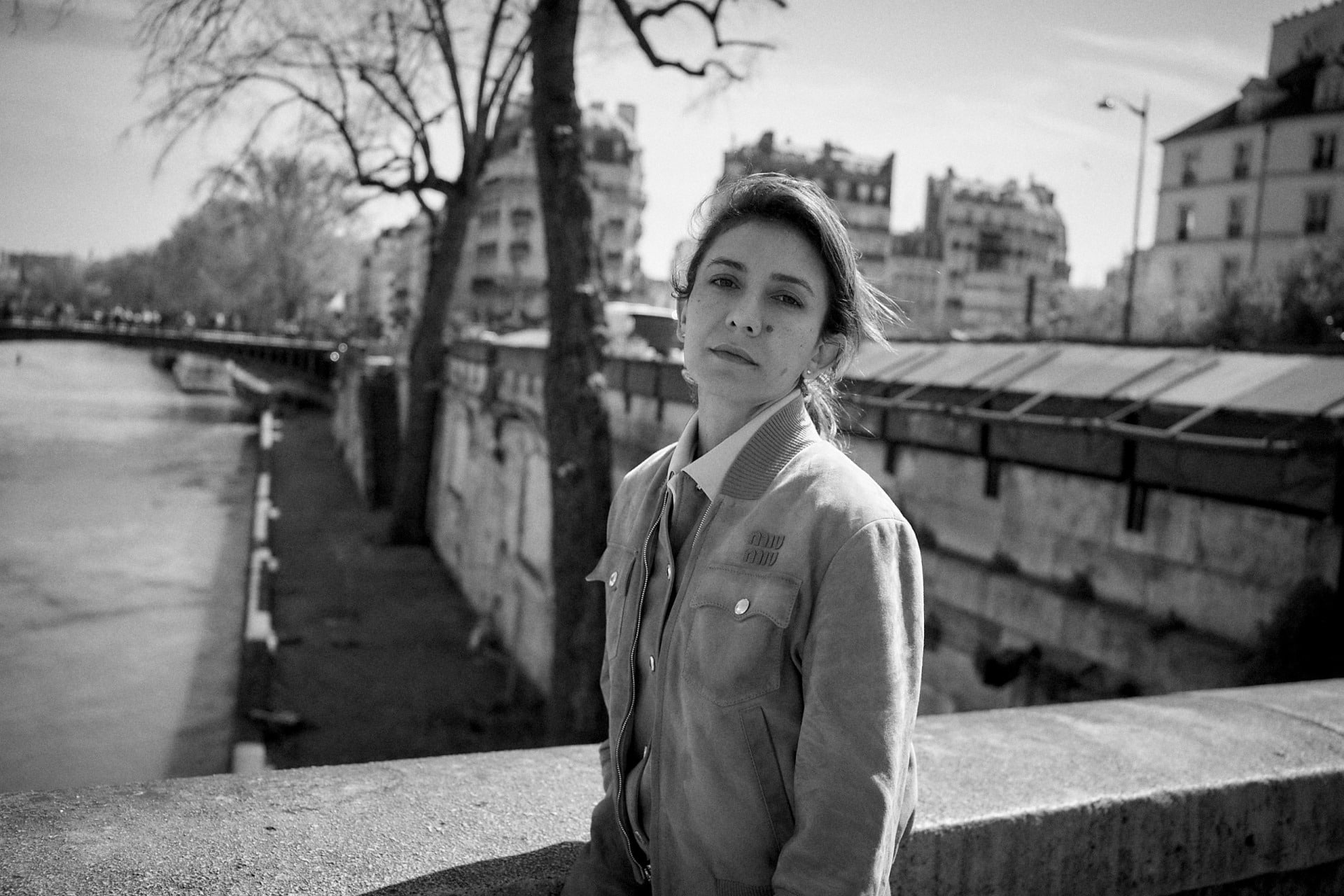

Still, a resurgence in queer cinema directed by queer filmmakers, has allowed for these stories to enter the mainstream discourse. Just look at the popularity of Céline Sciamma’s seminal work Portrait of a Lady on Fire, as well as the deliciously tense Shiva Baby directed by Emma Seligman. Both films’ lesbian love stories follow the tradition of Deitch’s work by culminating in an almost hopeful ending, illustrating that lesbian narratives can go beyond tragedy. This is why it’s so necessary to revisit films like Desert Hearts, it inspired and paved the way for the groundbreaking queer cinema we can enjoy today.