Benoît Delhomme was never meant to direct Mother’s Instinct. The psychological thriller, which stars Jessica Chastain and Anne Hathaway as neighbours Alice and Celine, 1960s housewives in suburban America, was intended as Olivier Masset-Depasse’s English-language remake of Duelles, itself loosely based on the French novel Derrière la haine by Barbara Abel. Three days before shooting was due to start filming in New York, the original director had to drop out. Delhomme, who was already signed up on the film as director of photography, was asked by Hathaway and Chastain if he would take the lead. They had worked with him on previous films, and trusted his process. “They knew I wasn’t just interested in the lighting and the framing. But with telling the story,” he says.

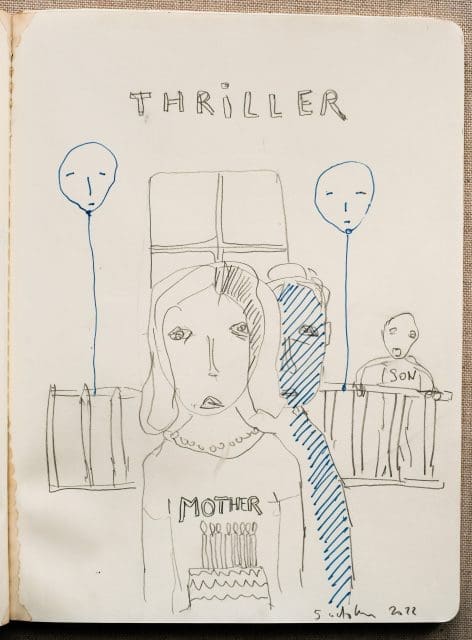

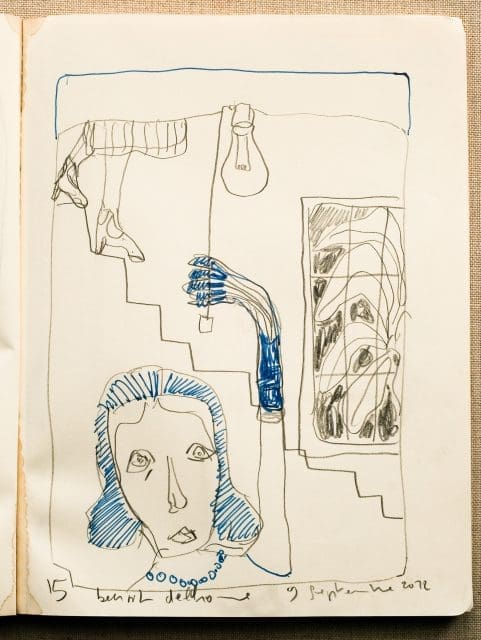

Under Delhomme’s direction, form and content reach an exquisite tension. The story, which tracks the pair as their chocolate box existence unravels when Celine’s son dies in a tragic accident that Alice might have—but ultimately couldn’t—prevent, is given a proportioned pacing and pathos, unfurling with a symbolic precision possessed by the best film noir: a peanut allergy becomes a dramatic plot point, as does a string of pearls. The jealousy, paranoia and emotional breakdown agonizingly exposed in Chastain and Hathaway’s performances (Chastain and Hathaway’s husbands are also skillfully played by Anders Danielsen Lie and Josh Charles). Yet with his photographic eye, Delhomme eeks out an added beauty with an emotive language that only images can speak: Celine cradling her dead son like a pietà, a tiny toy ambulance lying abandoned in the grass.

A RABBIT’S FOOT speaks to Delhomme about anxiety, the influence of Hitchcock and the psychological power of props.

Kitty Grady: Being called on so last minute to direct this, your first film, was that terrifying or liberating?

Benoît Delhomme: I really like to be on the edge of a cliff. You don’t have much time to think. You don’t have time to be scared. I’ve seen so many people trying to make their film for years and it takes so many years to find the finance, to find the cast, to find the actors, to produce the story. I said, okay, I’ve got a good story. I’ve got two incredible actresses. Plus two male actors who were really good too. I’ve got everything to make a film. I guess it’s a bit like if you are a chef and you have all the ingredients and they tell you: now you need to cook this.

KG: It’s still possible to mess it up…

BD: Of course… people think it’s easy when you’ve got everything. But no, making a film is day after day on the set. The decisions you make every single minute. So it was like a blank page. I did not have the storyboard, nothing was in place. I’d only seen the original movie once before and I decided not to rewatch it as I didn’t want to be influenced by it. With Jessica and Anne, we just had one read-through the day before the shooting started, but we had no time to talk about characters. Anne and Jessica—I think they trust my sensitivity about actors. They kind of knew that on the set I can feel what they are doing, what they want to do, because if you are a really good cinematographer, you constantly try to capture what the actor wants to deliver.

KG: In those three days, what did you focus on, what did you decide you wanted to bring to the film?

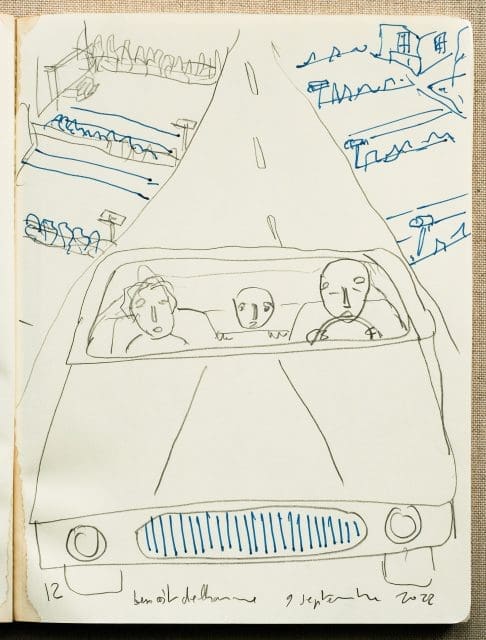

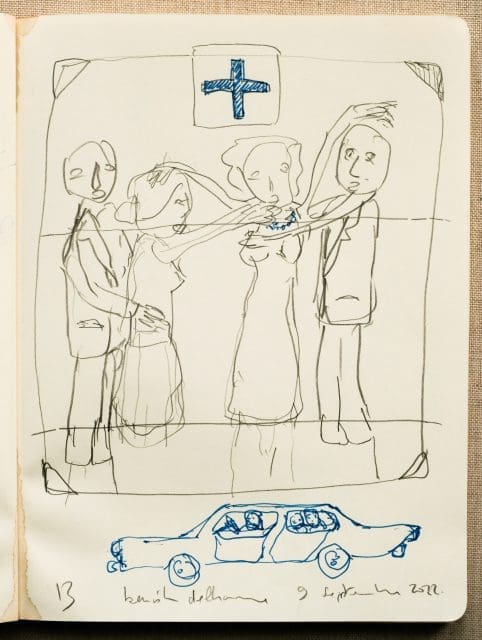

BD: I was quite lonely because it was also this time when you could not really meet all the crew. Everything was done on Zoom because people were still scared about Covid and everything. I had to think about how the film relates to me. If you’re a cinematographer, a film relates to you but it’s different if you are suddenly a director. So I said okay—what is common between this film and my life? How do I see these two women? How can I project myself onto this story? And certainly something I wanted to work on was the anxiety of the characters. To play with the anxiety of these two women, what’s happened to them. When you have a child, you can also lose that child. Obviously, when you have a child, this is your treasure. But protecting your child too much can drive you crazy, too. I’ve got a young son. He was something like four years-old at the time we were shooting. I can certainly project myself as an anxious father for sure. And because of the thriller structure of the film, exploring this one character, you don’t know if it’s something she is really experiencing, if things are true or invented. And it’s a kind of Hitchcock thing, where you never know if you see the truth or not. And is [Alice] inventing something? Is it only inside her head? I thought, I know how to deal with that, because I feel I’m an anxious person in life.

KG: It’s so well done how you never know which reality you are questioning. You don’t know who is crazy and who isn’t. But I think that the two characters are essentially one. Like the amalgamation of one person, like this mirror effect.

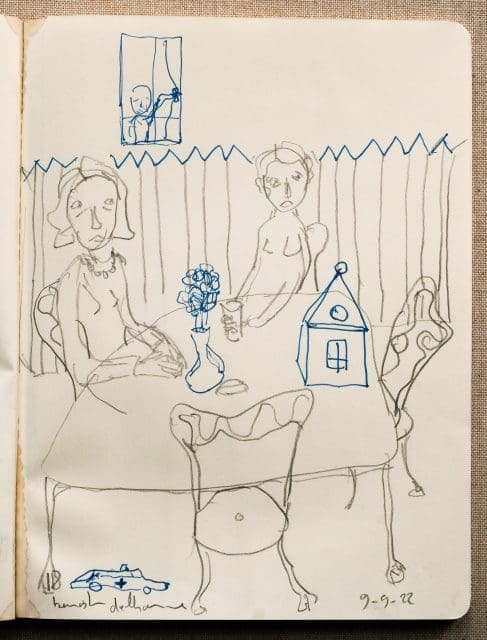

BD: I’ve always loved this kind of thing. The symmetry. You have these two houses side by side, with the two gardens connected by this hole in the hedge. And I love the symbolic space of that. To start, it’s very much like a theatre. There is this stage-like, old fashioned structure in this film. Celine stage right, Alice stage left. They both have busy husbands and they both have a child, a son. You think they are very balanced. The two kids are friends; the two women are friends. It’s Celine’s birthday. And very quickly this beautiful balance collapses. And how do you cope after the balance goes completely off? Celine has lost her child. How can life go on after this?

KG: I loved the contrast in the colour of their hair. It’s very Jackie and Marilyn… Was that a reference?

BD: Yes we spoke about Jackie Kennedy, especially for Anne. And Tippi Hendren, for Jessica. They used the same hair shape as in Tippi’s Hitchcock movies. But I didn’t plan this, I didn’t work on this. These looks are looks they had made themselves on their own, which I love. Jessica and Anne had this kind of very strong idea about their character, what they were going to wear. In a way, it’s nearly as if I had done a documentary about these two characters. I just arrived to film them.

KG: And your job was just to capture them as beautifully as possible. And be empathetic to the actors and listen to how they wanted to tell the story.

BD: Anne, Jessica… they’re incredible actresses, and they had worked on the characters on their own. I was impressed. I thought, I take what they want, I take what they do. What they brought was so beautiful, and their chemistry was so good. Anne and Jessica, I didn’t try to redirect them. I was observing them. I wanted to give them freedom to express the characters they had built in their head. I said, okay, I’m not Mike Nichols. Let’s work in a different way. I would have loved to be stronger director in terms of directing the performances. But I thought, no, I’m interested in doing it in a different way. To be quite silent about their performances. I thought it would give some kind of consistency to the character, because let’s take them as they are.

KG: How was it working with the young actor who plays Theo [Eamon Patrick O’Connell]?

BD: With a child, it’s completely different. Often they come and their parents have been rehearsing with them and they’ve done their homework. So you kind of have to control how they perform. And here it was complex because my God, I’m asking this young kid to play a very emotional, dark part. When you lose you best friend at nine years old how can you go through this? I completely used the fact I’m a father. Anne and Jessica helped me a lot working with him. They were both the mother of their child in the film.

KG: The era Mother’s Instinct is set in is the 1960s, which I believe is around the time when you grew up. Did it feel nostalgic to recreate that time?

BD: Yes. I was born in 1961 and I was living in the suburbs of Paris, which is not New Jersey, of course. We were living in a tower block, my parents didn’t have the level of money they have in the film. But I remember my mother was dressed in a similar way and inviting people for aperitif and for dinner. I could remember all this. So in a very different country and different class, but yes, I could relate to that. And I love, obviously, I love movies like [Wong Kar-wai’s] In The Mood For Love, the 1960s setting. It’s an incredible era for design. I love the furniture, curtains, everything.

KG: I noticed it’s a film where props are really important, in their symbolism and as narrative devices—from the birdhouses, to the little ambulance at the beginning, which really plays with this sense of scale. Or the pearl necklace… Can you please talk a bit more about your approach to props and objects?

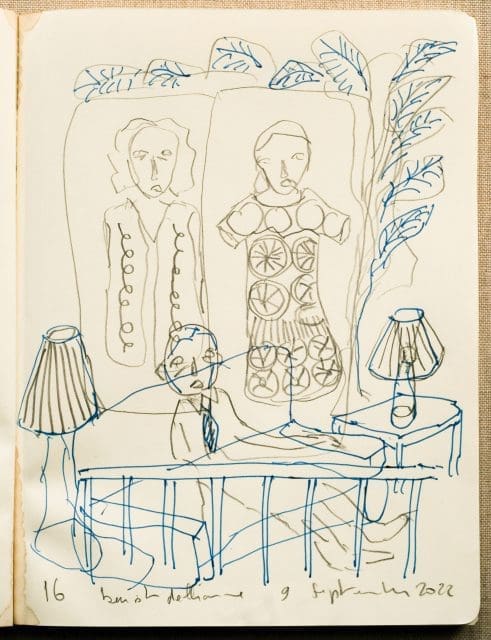

BD: With the ambulance—funnily enough nobody really understood what I wanted to do there. Because this was something which wasn’t in the script. At the beginning Alice is watching Celine in her garden doing things we don’t understand. In the original film she was only cutting flowers. I needed an element of drama. So I thought, what about a toy ambulance, a symbol we will see later on in the film. You know something bad is going to happen. David Lynch would play with things like this; finding something in the grass. It’s a detail, but also, I’m a painter, so I work a lot on images of my own when I’m not working on films. I would have loved to develop this more in the film. Hitchcock worked so much with symbols. It was super planned, in his storyboards. You had shape in Vertigo. Shapes connecting, dissolving. It’s a psychoanalysis thing for Hitchcock. You can find objects in the film which are going to take you back to the character. For me, this is what cinema is about. Certainly cinema is about dialogues and actors. But I think symbolic images and objects have a soul. Cinema can give them a soul.

It’s a psychoanalysis thing for Hitchcock. You can find objects in the film which are going to take you back to the character. For me, this is what cinema is about. Certainly cinema is about dialogues and actors. But I think symbolic images and objects have a soul. Cinema can give them a soul.

Benoît Delhomme

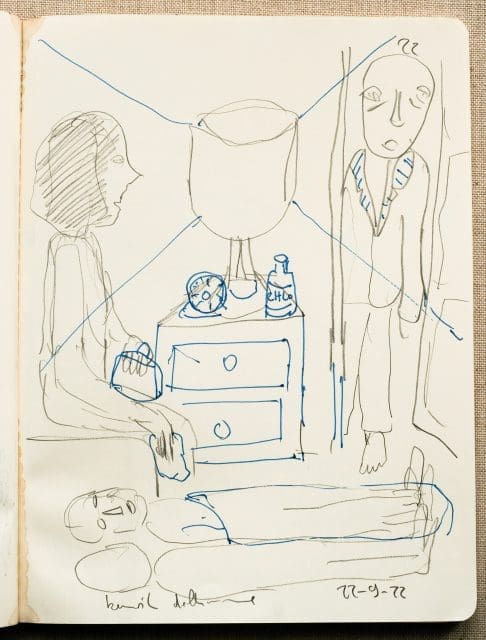

KG: I felt like the film had a lot of breathing space. It’s intense. But these moments of symbolism weren’t crowded. One of the most beautiful shots in the film is when Max dies and Celine is holding him, and then you see the blood on his head and then her nails, which are also this red acrylic.

BD: I love this shot, too. This is exactly the kind of thing I love. Suddenly the camera comes to some detail and stays in the detail. I think movies are about what you show, but also what we cannot show and I think I didn’t want to show the death of the child. But I need to find a way to show the boy passed away and I thought it was the most emotional way to do it. When I made this shot I thought: I could be a director. This is a statement as a director for me. With this shot suddenly, you know, the film is coming to another level. I really believed in this.

KG: Do you think you’ll be directing more films?

BD: I would like to do another film, for sure, where I could prepare, make it my own—not two days before the film starts. I would like to make a film where I bring all my ideas, work months before with the art department and the designers closely. This film, I jumped on it. So I couldn’t make it completely on my own from the start. You think you know cinema as a director of photography. You work for 40 years, you think you know everything because you see one side of it. I thought I knew more about actors than I did. And suddenly, you wake up in your hotel room at 5 a.m. You say, okay, today I have to do that. This scene, this scene and this scene, you realise it’s a complete new start. It’s a different energy, it’s a different position, different attitudes. It opens something new. It’s a different brain to be a director.

Mother’s Instinct is out now.