You know Jeff Bridges very well. Or, you think you do. You’ve seen his face on the big screen as iconic characters like ‘The Dude’ in The Big Lebowski, sinister villains like Obadiah Stane in the first Iron Man, and in acclaimed films from the Coen Bro’s True Grit to Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show to Steven Lisberger’s cult favourite Tron. But what you might not know is that the Hollywood legend is as obsessed with the still image as he is with the moving one. Bridges first fell in love with the act of taking photos when his wife gifted him an analogue camera which he would use to shoot on the set of Starman. It was a Widelux F8: an all-time favourite of Bridge’s, and a camera you’ll see mentioned plenty in the conversation below. “The Panoramic swing-lens seems to capture the way the human eye sees,” he describes, “as though the camera has peripheral vision.”

The Widelux has been so prominent in Bridge’s life that he’s recently taken it upon himself to bring it back to life, after discovering that it was discontinued in the 90s due to a factory fire. The new project tells you everything you need to know about his appreciation of the craft, and if you have any doubt that the man was born to capture life through the lens, look no further than his 2003 book Pictures: Photographs by Jeff Bridges and its 2019 sequel Jeff Bridges: Pictures Volume Two, which collect magnificent panoramic shots taken on film sets and beyond.

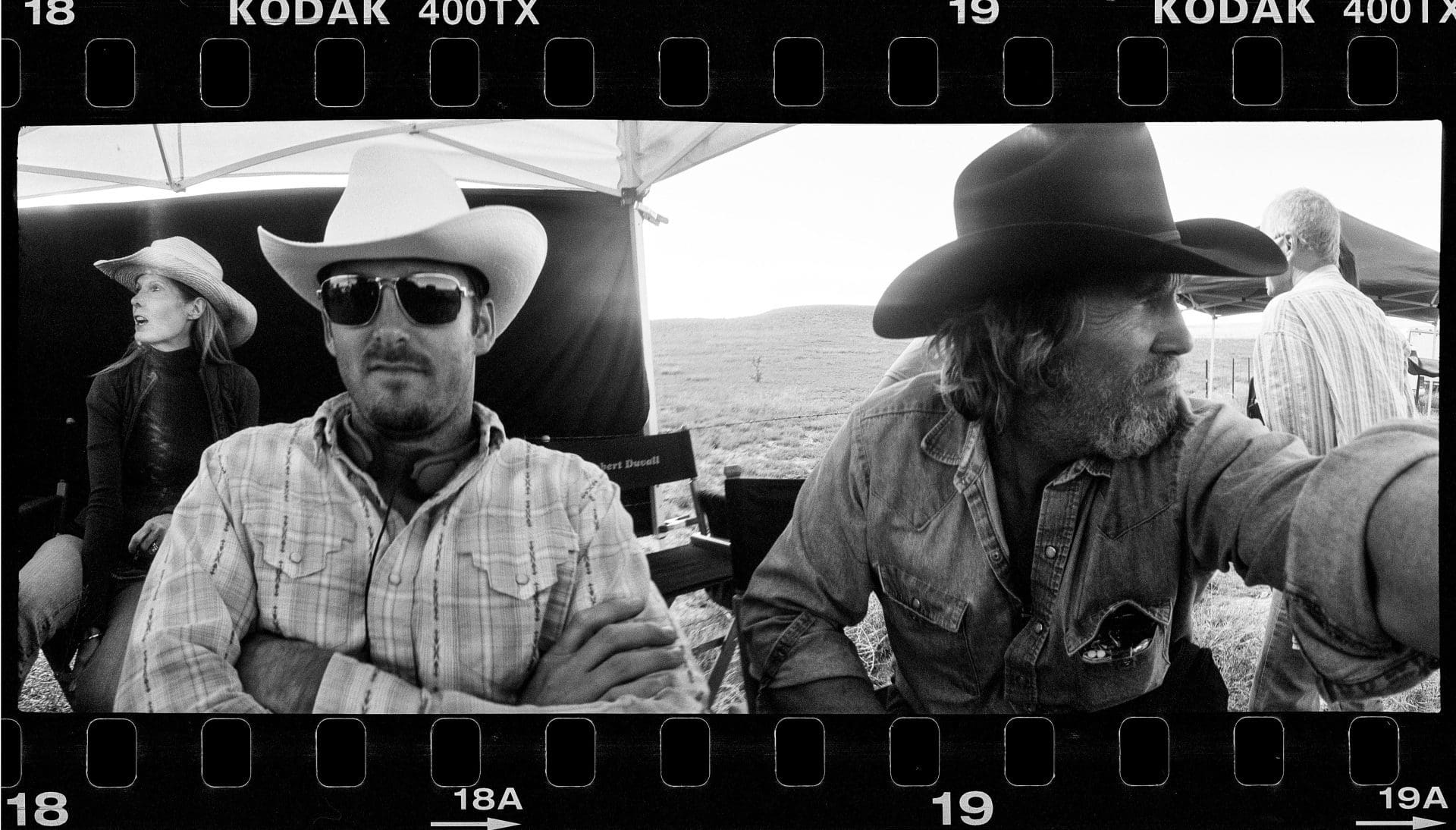

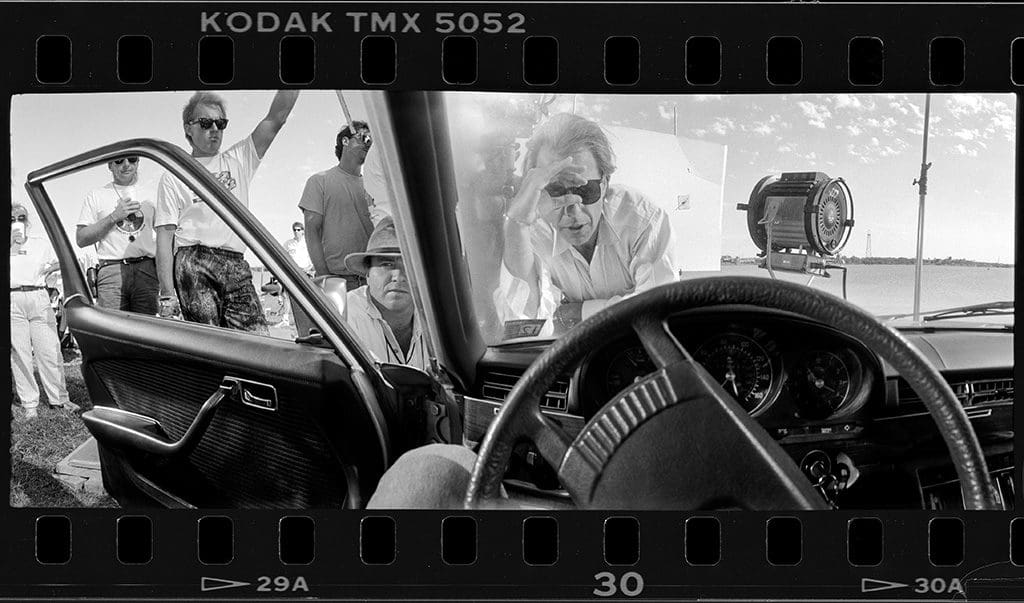

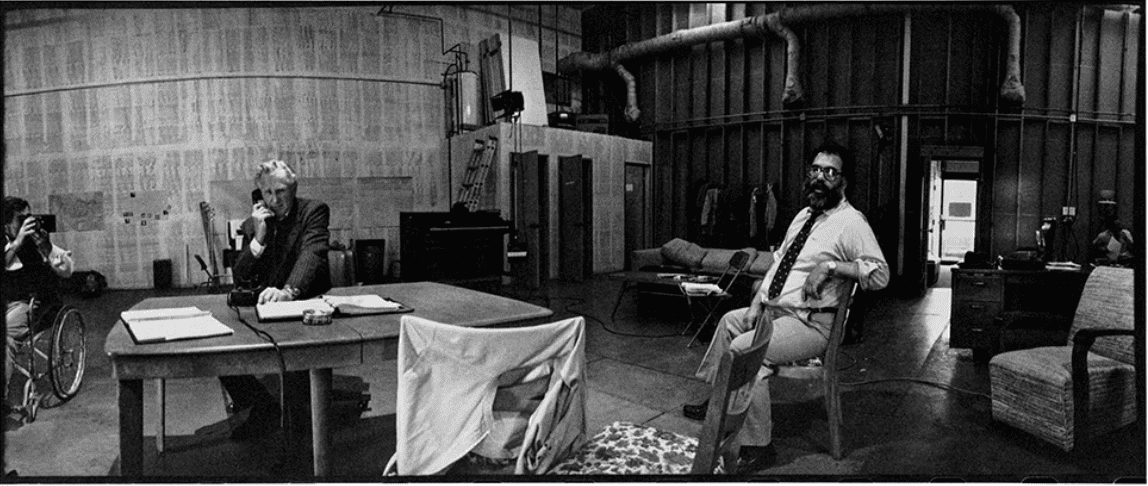

Below, Jeff speaks with A Rabbit’s Foot Creative Director Fatima Khan about his love affair with the Widelux, the crossroads between photography and cinema, and how his lens brings him closer to his own personal American spirit, alongside exclusive images (featuring a few familiar faces) from the photographer’s archive.

What drew you to shooting on a wide-format lens, rather than a smaller film like frame of 35mm?

Well, my particular Widelux does use 35 mm. I first started taking pictures in high school with my father’s Nikon—I turned my bathroom into a darkroom. I enjoyed shooting my friends and being in the darkroom developing and enlarging. But my interest in the Widelux started on my wedding day when the photographer, Mark Hanauer, came to photograph our wedding using a Widelux camera. When I saw the results I was knocked out by the movement and the excitement and the format itself—which reminded me of 70mm cinema. As a wedding gift my wife gave me my first Widelux camera.

Is there a photo you feel the proudest of taken? Were there any that required bravery to shoot?

As I look through my photographs—it’s that corny thing that actors say when they’re asked about their favourite movie. They’re like children. And I feel the same way about my photographs. There are certain photographs that stand out in the small books that I make for each movie. Each of the books and photographs are like children. They represent movies and lifetimes that I can revisit by looking at these pictures. It’s really impossible for me to pick a favourite one.

Regarding bravery—I remember a movie I made called Blown Away. To prepare for my role I accompanied a fellow who was a member of a bomb squad. They’d draw straws when there was an incident. One day, they got a call about a fellow who was under a car with his hand taped to a bomb. The fellow I was with drew the straw and had to go investigate this incident. So, I asked if I could go along since I was playing a bomb squad fellow—and he said okay. I got so involved in what I saw through the camera that I wasn’t really aware of where I actually was as my camera was getting closer and closer to this bomb and to the fellow under the car. I guess that was perhaps the most dangerous that comes to mind at the moment.

What’s a character you’ve played that you feel best reflects the American Spirit, and why?

Starman comes to mind. And his line about what he loves most about us human beings—and I think that also can be applied to what I love most about the American spirit—is that we are at our very best when things are worst.

Tell us about your vision behind the camera you’re developing. What would you like to contribute to photography with this project?

Well, I was sad to find out that the Widelux factory had burned down in the mid 1990s. Since I fell in love with the Widelux it’s just about the only camera I use— besides the occasional iphone photo.

During an interview with Charys and Marwan of Silvergrain Classic magazine, I asked if they thought it was possible to revive the camera and if anyone would be interested in doing this.

I thought it was just a fantasy, but they called me back and said they thought it was possible, and that they were interested. And boom—the dream started to materialize. And it got more and more exciting and more and more real. And here we are just about to bring this into reality.

As far as what I’d like to contribute to photography with this project—well, there’s that whole deal about throwing the baby out with the bath water. Digital photography certainly has its value. But analogue film photography is a wonderful process. It has special qualities that can’t be produced with a digital camera. The time and intentionality it takes to compose the photograph, to develop the film, and to make a proof sheet, only to discover the surprise of what appears. It would be a shame to lose the process of analogue photography and this excitement of discovery. It’s all worth preserving and passing on to the next generation.

There are certain things the Widelux can do that digital cameras cannot. I shoot with Kodak or Ilford 3200 ASA. Since I work mainly on the set where there is very low lighting, I’m able to shoot with the Widelux, at F11 @ 1/15th of a second. I can handhold my camera and most cameras you just can’t do that. I like to get close to my subjects. I do some landscape photography but primarily I like to get as close to my subjects as possible and the film and the Widelux allows me to do that.

What fulfilment does photography bring to you that no other medium, including cinema, can?

The word that comes to my mind is surprise. And all the things I do creatively have that element of surprise. I suppose one of the things that photography brings that movies can’t is that you can immediately pick up a picture and look at it and it brings you back to that moment in your life. That’s something wonderful about the books I’ve created. I can look at these books and photographs and immediately return to those lifetimes. But basically, most creative endeavours have that element of surprise. You never know what you’re going to get. And I love that.

The selection of your photos we’ve chosen to feature are full of familiar faces—the likes of Bob Dylan, Francis Ford Coppola, Jane Fonda and Robin Williams, among others. Is there a through-line—a character trait, perhaps—that unites them all, that made them fascinating subjects to you and made you want to capture them through your lens?

These pictures are a bit like home movies, but quicker. In a glance, I can be transported back to when they were taken. They serve as, almost, a drug that takes me back to other lifetime. I say “lifetime,” because I consider each movie as one—each character I played, each of the weeks, months, I spent with these folks were lifetimes. When we make a movie, we do it with a bunch of people who are very different, with loads of different opinions, ideas of what’s right and wrong, good and bad. The common denominator is that we all want to make something beautiful, something relatable, something we can look at and say, “Shit…yeah man, that turned out even better than I thought.” We cash in on the law that 1 + 1 = 3. All our intentions come together to produce…well, magic…turning water into wine, lead into gold. It’s an alchemy of sorts.

ON PETER BOGDANOVICH

What a weird, wonderful life, that of a movie actor. Peter Bogdanovich, the director of The Last Picture Show, once said, “You know, making movies is only about a hundred years old. It hasn’t been proven that making movies is a healthy thing for human beings to do.” I guess the jury’s still out on that one. Maybe it’s not good to live a pretend life for that long. Maybe it’s not healthy to pretend to be another person. I understand what he was saying, and both smiled when he said it.

ON FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA

What I love most about making movies is that it’s a communal art form. When I watch a film I’ve been in. I see friends, I see stories that could have been movies in themselves, and sometimes I just think, “Gee, Francis cooked us a great lasagna after that one!”