Party tip. If you ever find yourself chatting to a couple and the small talk is not landing, just ask them how they met. This is almost always a mutually satisfying exchange. I say this as someone who is incurably curious about other people’s personal lives and two years into a relationship, still wide-eyed and dopey when I re-tell our origin story to strangers. Beginnings are catnip for movie makers. The meet cute. Despite their popularity, films of a decidedly romantic nature have been (unfairly, I’d argue) ridiculed for their unrealistic and fantastical lens on falling in love.

Relationships do not follow such a linear pattern of events, the choreography too neat, they say. Where two people meet — during an 18-hour car journey from Chicago to New York City, a tennis game, or eyes meeting one another across a large fish tank at a party — misunderstandings or fuckups (sometimes both) occur, before sentimentally surrendering to the fact they have found their person.

And yet, of all the ‘escapist’ genres this one is surely the most grounded in reality. I always think about author Roxane Gay’s defence of Pretty Woman, that even with its problematic connotations, of which there are numerous, it’s the film she cannot help but return to time and time over: “It’s romantic and absurd,” she says. “And romance is absurd.” Art is consistently imitating life; people do fall in love and tell people they love them every day. The latter marks another beginning. More significant, soul-baring and arguably scarier: hoping that feeling is met with a mutual surety. The most memorable of cinematic confessions follow their own formula. Sometimes there are no words at all, interruptions, pop music, startling responses.

During an annual Carrie Fisher archival frenzy, I happened upon that exchange in The Empire Strikes Back, when Princess Leia finally professes her love for Han Solo.

His response? “I know.”

In fairness, this was just before he was frozen alive in carbonite so, you know… mixed emotions. Besides that, there’s something just overwhelmingly human and un-schmaltzy, about it. Harrison Ford did, in fact, re-write that line with the director during filming: “If she says, ‘I love you,’ and I say, ‘I know,’ it’s beautiful and it’s acceptable and it’s funny.” Some may disagree, but I always read it as his, quasi-infuriating, way of saying ‘I love you, too.’

Teenage romantic comedies are the opposite, comparatively void of vagueness. The finest of the crop wears its heart on multiple sleeves. Unhardened by previous heartbreaks. It’s Julia Stiles reading her poem through tears in 10 Things I Hate About You (“most of all I hate the way I don’t hate you, not even a little bit, not even at all.”). It’s John Cusack holding up a boombox blasting Peter Gabriel’s In Your Eyes. Even if you haven’t watched Cameron Crowe’s Say Anything it is still one of the most recognisable cinematic displays of affection.

There’s something infinitely lovely about a wordy speech. You know the ones that contain a kind of desperation to get the feeling out, even if there’s a risk it’s not reciprocated. Whether it’s just a girl standing in front of a boy asking him to love her in Notting Hill. Or Tom Cruise in Jerry Maguire telling Renée Zellweger after a ramble, you complete me, opening his mouth to continue before she tells him to shut up.

To a cynic? Too over the top, too potentially humiliating in actuality, too much. For hopeful romantics? Lyricism really is a lasting love language and, well, an action we already engage in to varying degrees (albeit on a smaller scale). Listening to Desert Island Discs recently, I couldn’t help but feel good at Jamie Dornan describing playing The Beach Boys’ Forever for his now-wife, Amelia: “I just watched her reaction, she just seemed instantly impacted by the song and it seemed appropriate it would be our first dance [song]. The first line, if every word I said could make you laugh I’d talk forever, is pretty much how I feel about my wife.”

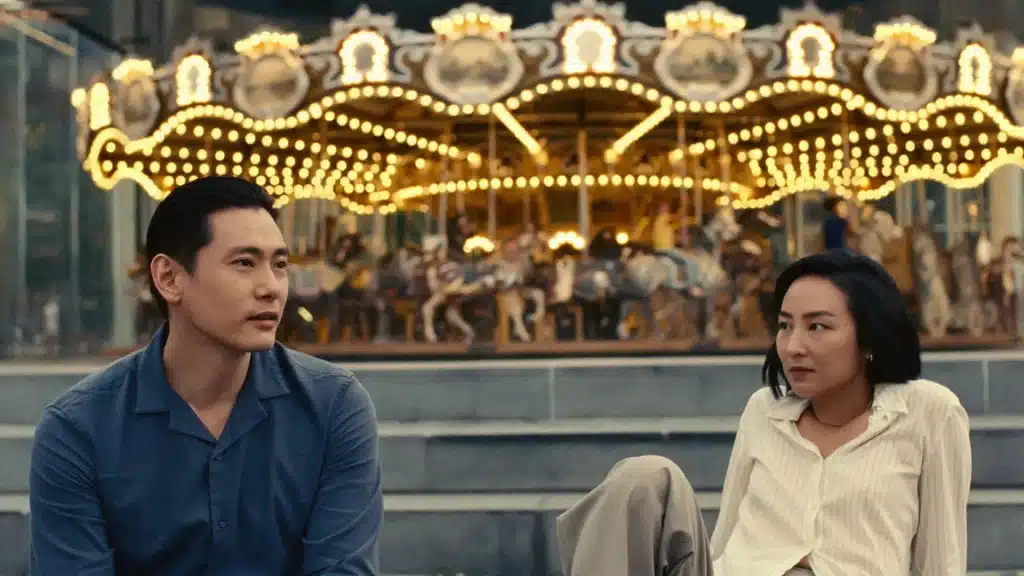

Then there’s the sound of silence. It is impossible not to be moved by that final scene in Past Lives, one of the most exquisite renderings of love and loss I’ve seen in recent years: two people gazing at each other; a soundless ‘goodbye’ and ‘I love you’ at the same time. In a similar vein, Sofia Coppola resolved that the whispered dialogue pre-kiss in Lost in Translation between Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson should be inaudible, a secret between the giver and receiver. “I was going to figure out later what to say and add it in and then we never did,” according to Coppola. “It was between them.” This feels tantamount to writer Toni Morrison’s instruction that one has to work very carefully with what is in between the words. What is not said.

In the end, there’s something infinitely lovely about a wordy speech. You know the ones that contain a kind of desperation to get the feeling out, even if there’s a risk it’s not reciprocated. Whether it’s just a girl standing in front of a boy asking him to love her in Notting Hill. Or Tom Cruise in Jerry Maguire telling Renée Zellweger after a ramble, you complete me, opening his mouth to continue before she tells him to shut up. Before she delivers the even more quotable you had me at hello. Of all the greats though, for me Nora Ephron’s When Harry Met Sally is the greatest.

Harry: I’ve been doing a lot of thinking, and the thing is, I love you.

Sally: What?

Harry: I love you.

Sally: How do you expect me to respond to this?

Harry: How about, you love me too.

It has everything. Romantic, yes, but all the other sub-emotions contained within that experience. A nervousness; questions, endless questions; realising that the very person who makes you the happiest can also be maddening. Those three loaded words may arrive unexpectedly. It doesn’t matter. Love is complicated but sometimes as simple as Harry confessing after twelve years of friendship, “I came here tonight because when you realise you want to spend the rest of your life with somebody, you want the rest of your life to start as soon as possible.”