After publishing her first novel ‘about a girl who lies in her room and takes drugs,’ the Swedish writer Tone Schunnesson thought she was going to write a dense, historical novel. Several journalists called her an it-girl, and she was afraid she wouldn’t be taken seriously as a writer. ‘I was afraid I would be out tomorrow,’ Schunnesson says.

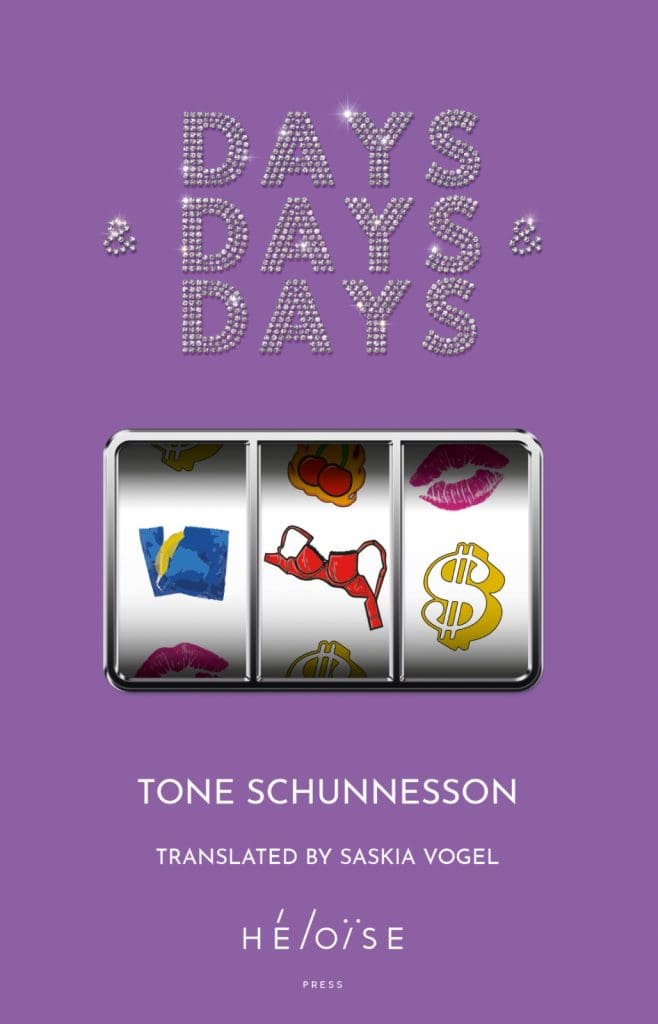

Tone didn’t write that historical, dense novel – at least not in the way one would imagine. And ironically, her second book Days & Days & Days came to be about an influencer. Bibbs is approaching forty, has a wardrobe full of free, expensive clothes but no savings, and her time in the spotlight is running out. Whereas she once lived off blogging, her career now consists of appearing in ads for collagen drinks and attending paid liquor events. When her boyfriend, Baby, suddenly breaks up with her, Bibbs needs money, quick – ten grand in a week, to be precise – to keep the lease on their shared flat.

In Days, we follow Bibbs in her reckless attempts to get the money while, her flat, career, and image are slipping between her hands. Schunnesson has referred to Bibbs as a less stylish and older version of Caroline Calloway, the American influencer who faked her way into Cambridge and, in 2023 published her memoir, bluntly titled ‘Scammer’. Meanwhile, Days has been described as – quoting it’s blurb – a pitch-perfect study of success and destruction, dependence and betrayal, celebrity and anonymity. Yet, her fears of a Bibbs-like destiny considered, Schunnesson writes about these topics in a way that feels timely and timeless in a perfect combination, capturing the contemporary in a way that might one day serve as a record of the absurdity and fragility of our times.

Although Schunnesson’s name is still unknown among many British readers, the writer has become a name on the Swedish cultural scene. In addition to her two novels, Trip Reports and Days, she has reimagined Anna Karenina and Jane Eyre for the stage. She is a cultural columnist and podcaster for the Swedish newspaper Aftonbladet, where her subjects include everything from politicians to the Beckhams and Bret Easton Ellis. Last year, she published ‘Tone Round-Trip’, a series of Gonzo essays about the Swedish election, and at the moment she is working on a novel (which she doesn’t want to talk about). In the meantime, Days will appear on stage in Copenhagen this coming spring, where Schunnesson herself appears in a tiny cameo role.

Being Norwegian, I have the luxury of having followed Tone’s writing for years. I remember reading her essay on celibacy as a feminist tool in the modern age, which felt refreshing and intriguing in a pink-painted feminist discourse. When re-reading Days in preparation for this interview, this time in English – a translation (by Saskia Vogel) recently published in the UK by Heloïse Press – I felt like the story existed between languages, just like this interview, Tone speaking in Swedish, me in Norwegian.

With Tone in a snowy Stockholm and me in a gloomy Glasgow, we spoke about fame, Klarna, victim narratives and Anna Karenina.

Emma Aars: Hi Tone, how are you?

Tone Schunesson: I’m good, I think! I just came back from spending three months in Berlin, where I have been writing my new novel. Optimistically, I had imagined I would go away, write the book, and return to Stockholm and do something else. But I forgot how writing doesn’t really work that way, so now I am back home, feeling like a failure. I don’t know, in a kind of pre-Christmas depressive mode. At least I returned to a snowy Stockholm, which is wonderful.

EA: Did you get to write anything at all?

TS: Yes, absolutely. But I want my writing to be like a factory, where I sit down, let it happen, bam bam bam. Getting shit done like a real girl boss! But writing doesn’t work that way. It’s crazy thinking how everything in life follows that logic except for writing.

EA: Do you want to talk about the book?

TS: No, not at all! Don’t jinx me! But since I know what the book is about, I wish I could sit down and dominate the text. Instead, the text dominated me.

EA: But we are here to discuss your novel Days Days Days, which was launched in the UK this autumn. How has it been returning to your book in a different language, three years after it was first published?

TS: It has already been translated into Danish and Finnish, so I’ve talked about this before. When I went to England this autumn to promote the book, however, I realized I couldn’t read it over. I have read parts of what Saskia [Vogel] has written in her translation, which is magnificent. She has done such an amazing job capturing Bibbs’ inner voice, vibe –and all of that. But at the London launch, I realized how little I remembered. There were parts of the book I couldn’t understand how I’d written myself.

An even bigger psychosis is how so many Swedes believe that Bibbs and I are the same person—thinking that I’m walking around having done all these insane things I wrote about. That was probably my greatest fear when promoting the book again, being reminded of all the crazy shit I have written. But that’s how it was with my first novel, too, so I’m kinda used to it.

EA: I was thinking how common it has become to ask the author if the book is based on the author, and they all seem to answer “yes but no, no but yes.” Especially in Scandinavia, the autobiographical has become such a central paradigm for contemporary literature.

TS: But with Bibbs, it’s a complete no! We are not even close to the same person. The only real thing we had in common when I started writing the book, was our financial situation. I needed 100,000 kronor [about £10k] because I was slapped with a huge tax bill.

For a long time, I had tried writing about Bibbs without knowing how. I knew that she was approaching 40, and not at all thinking about having children. Not even thinking about the fact that she didn’t want kids, she was just living life on her own terms. There’s so much else that needs to come together when writing a novel; voice, tonality, form, storyline. I had a lot, but I missed – what to call it – a musicality, pace. When I write, I want everything to exist at a quite high pace, so when I suddenly owed money, it dawned on me—of course Bibbs needs money! Nothing makes you as effective but at the same time destructive as those things combined. And that became my entrance into the world of Bibbs.

EA: What made you write about an influencer?

TS: I’m very interested in influencers as part of the gig economy, more than the bloggers themselves, if you get what I mean. It has always been the economy behind this culture that has interested me the most. Like, when you go to any major city, and you see all these people who are famous now or were famous five years ago, you realize how short the lifespan of these jobs is. I like to compare being a girl and an influencer to being a guy and a football star. Both get retired at such a young age. It’s a bit like, ah, you hurt your knee, so now you are 29 and without a job!

EA: Time is almost like an anxiety that follows the reader through the book. Bibbs has a week to get the money, but generally, it feels like time is running out in all sorts of ways.

TS: Exactly, it’s about temporality. Bibbs became famous through her blog, and now the blog barely exists anymore. She moves on to Instagram, which eventually will be replaced by TikTok. So there’s a kind of temporality to her craft, which is subordinate to the medium. She can’t just move effortlessly from one platform to the next because she thinks it looks good. After I debuted with my first novel, Trip Reports, some journalists called me an it-girl, which made me afraid I wouldn’t be taken seriously by the ‘real’ literature [scene]. I was afraid I would be out tomorrow.

EA: Did you feel like you weren’t taken seriously?

TS: I think it’s rather my own greatest fear of being considered stupid. At the same time, I am interested in many things that old dudes in antique bookshops probably would consider silly. After Trip Reports, a novel about a young woman who lies in her room and takes drugs, I thought I wanted to write this great, historical novel. The tax bill made me lean into my fears and instead, I let myself write a book of our time, where I would deal with subjects that almost seemed anti-literary, yet through literary means. For instance, right before the book went to print, I changed up the name of a collagen drink Bibbs promotes, because this other collagen brand was slightly on point at that moment. When I decided to write something so time-specific, the novel came to me fairly quickly. I had tried to act smart towards myself for two years, and suddenly I couldn’t be bothered anymore.

EA: I find your references to cultural-commercial markers of our time particularly satisfying. Like when Bibbs participates in an art graduation project, sponsored by a financing company. As a reader you know it has to be Klarna, [in the way they have marketed themselves towards young people]. One recognizes one’s own life in those details.

TS: Exactly. Those timely markers are the reason why I love reading Bret Easton Ellis, and they feel so crucial for Bibbs’ world. I mean, Days became a kind of testament to our time. I focused on writing something about our time, just as Klarna says something about our time. And I believe that’s important.

EA: Who was your inspiration behind Bibbs?

TS: William S. Burroughs has a short novel named Queer, where he sketches out this character, Lee, who later became the main character in his more famous novel Junkie. The novel itself isn’t spectacular. It’s about Lee who runs off to Mexico, trying to get clean from heroin. He falls in love with a boy, yet there’s this constant tense and dark atmosphere which makes the book particularly important for me.

I was very inspired by the way Lee tells the story through long anecdotes, and I wanted to write a character who only talks shit. So it’s Lee, rather than any influencer, that made Bibbs. On the other hand, many other characters in the book are based on specific Swedish archetypes. They probably exist in all major cities, where one feels like an ‘I became a millionaire at age 29 from making jeans and now I’m doing nothing’ type, while the next says ‘I was a feminist but then I slept with a 17 year-old’, which I find hilarious. I thought a lot about this when writing the book, peak #MeToo. All these guys who sat at home, shit-scared someone would come to write about them. There are always so many losers in the nightlife scene, nonetheless, you also develop some kind of affection for them.

EA: The characters in the book are quite bleak each in their own way; cynical and self-absorbed, yet with a charm. You end up becoming quite attached to them, after all.

TS: That’s exactly how I see the nightlife, too. I recently read this Swedish coming-of-age novel from the early 1990s where everyone was starting their own businesses, which made me realize why everyone’s so awful in Days. They are all failed entrepreneurs and alcoholics. Funny and charming, but also assholes.

EA: I found it interesting how Bibbs blames Baby for having raped her, considering you wrote the book in the middle of the MeToo movement.

TS: It was a joke on my behalf, too. Feeling betrayed and alone, Bibbs felt some primal instinct where she was like ‘I will fucking tell the world he has raped me!’ – and what can you do? But she also reads the market, aware of the impact of what she says. She sees everything as transactional. In that sense, she really is an entrepreneur – she’s just a bit off when it comes to her branding.

At a very personal level, I believe Bibbs came to represent a form of anger I experienced myself during Me Too. There was no compensation for those who said ‘Me Too—but ok, where the fuck is my money’. I think that anger was embodied through Bibbs’ nonchalance. That being said, I believe she comes from a quite violent and destructive relationship, although it isn’t explicitly in the book. She’s blind to this violence herself and tries to express something she doesn’t have a language for, so we never know exactly what she has gone through.

I recently read this Swedish coming-of-age novel from the early 1990s where everyone was starting their own businesses, which made me realize why everyone’s so awful in ‘Days & Days & Days’. They are all failed entrepreneurs and alcoholics. Funny and charming, but also assholes.

EA: She mentions slightly disturbing things, but always anecdotally.

TS: Precisely. To say ‘I have been raped’ is considered the perfect trophy, built upon misogynous myths about ‘the perfect victim’—someone attacked by a stranger on the street, yet that’s rarely the case in real life. I think Bibbs struggles to admit for herself what she has experienced, which is why she’s able to tell this lie so cynically in the book.

I have started to think about being an influencer as living close to violence. Your own truths or convictions are always subordinate to the job. At one point in the book, Bibbs says ‘I don’t know if I would have worn these clothes if I could choose myself’, having been gifted pretty much everything she owns from brands in exchange for her image. This is comparable to living in a violent relationship. You can’t think clearly about who you are or what you want because everything can be dangerous, and this is something I felt about both her job and her relationship which makes her decisions a bit off.

EA: At least in Norway, Swedish culture is quite known for its political correctness. What kind of reactions did your book receive when it first was published?

TS: It’s crazy to think about—I didn’t intentionally write the book critically, but I can see it that way in retrospect. I guess I’m not particularly self-conscious while I’m in the middle of my writing. Nobody in the media mentioned the rape thing, really. What got criticized the most was how Bibbs is such an annoying character. I found this to be a funny, misogynous twist. The silence around the rape felt a bit artificial, but it’s a thing that is hard for people to talk about.

I did a reimagination of Anna Karenina for a play last year, where I wrote Anna’s character as an addict. She treats the people around her like shit, while also being a victim of her circumstances, in a similar way to Bibbs’. I work a lot with twisting and turning the role of the victim, breaking with the idea of a victim being a better human, or reacting better than their abuser, which I still think people find it hard to talk about.

EA: How did you adapt Anna Karenina for the stage? It’s quite a dense classic.

TS: When I wrote the play, her opium addiction became my pathway into the character. I was looking for the void in the story when I read the novel. Tolstoy doesn’t address addiction directly in the book, but it clearly exists between the lines. Reading Anna through her substance abuse, I began to understand how to write her as this difficult, complex character, as opposed to a feminist fantasy.

EA: You are a writer across the line, doing everything from columns to podcasts to theatre and fiction. Is there something that binds it all together?

TS: I initially thought I wanted to be a novelist, but writing plays made me realise I wanted to work with people. Everything becomes so much better when done together with others! I love engaging with other people’s lives, and for other people to engage with mine, and I believe I got my column for Aftonbladet based on my interest in why people do as they do. However, I have a 10-year plan where I will try to phase out everything I hate, but I don’t dare to say what in case any of my bosses will read this! Novels and plays are my core, everything else is there to sustain this.

EA: Do you write every day?

TS: Yes, but not necessarily my novel or a play. Last year, I covered the Swedish election for Aftonbladet, so I had to write on this every day. I also have my column every other week. And of course, I also need days where I am completely off. Then I usually end up walking through the city, window shopping, and drinking bubble tea. I actually write the best on the weekend, when everyone else is busy with their own stuff.

EA: And a final question… what has been a recent literary highlight?

TS: I interviewed Bret Easton Ellis for my podcast about his newest novel, The Shards.

EA: Is he a kind of literary idol for you? You mentioned him earlier.

TS: Not really – I was not a huge fan of him until I read The Shards this summer, and absolutely loved it. You know the immersive feeling you had reading a book as a child? It was exactly like that. I have always been obsessed with glamour and fame and all of that, so I guess that’s where Bret comes in. On the pod, we spoke about Lindsay Lohan, serial killers, evil gays, and stuff like that. It was great.