Franc Roddam grins, “Oh that scene. Yes, well, that was actually improvised by Phil Daniels.” It’s perhaps the most famous piece of dialogue in his 1979 subculture classic Quadrophenia, and during a segment where Daniels’ beat-up Mod loser Jimmy is on the edge, only for his scooter to get knocked over by a local postman. “Phil didn’t tell the stunt driver he was going to improvise, so the postman’s reaction and surprise are very real!”

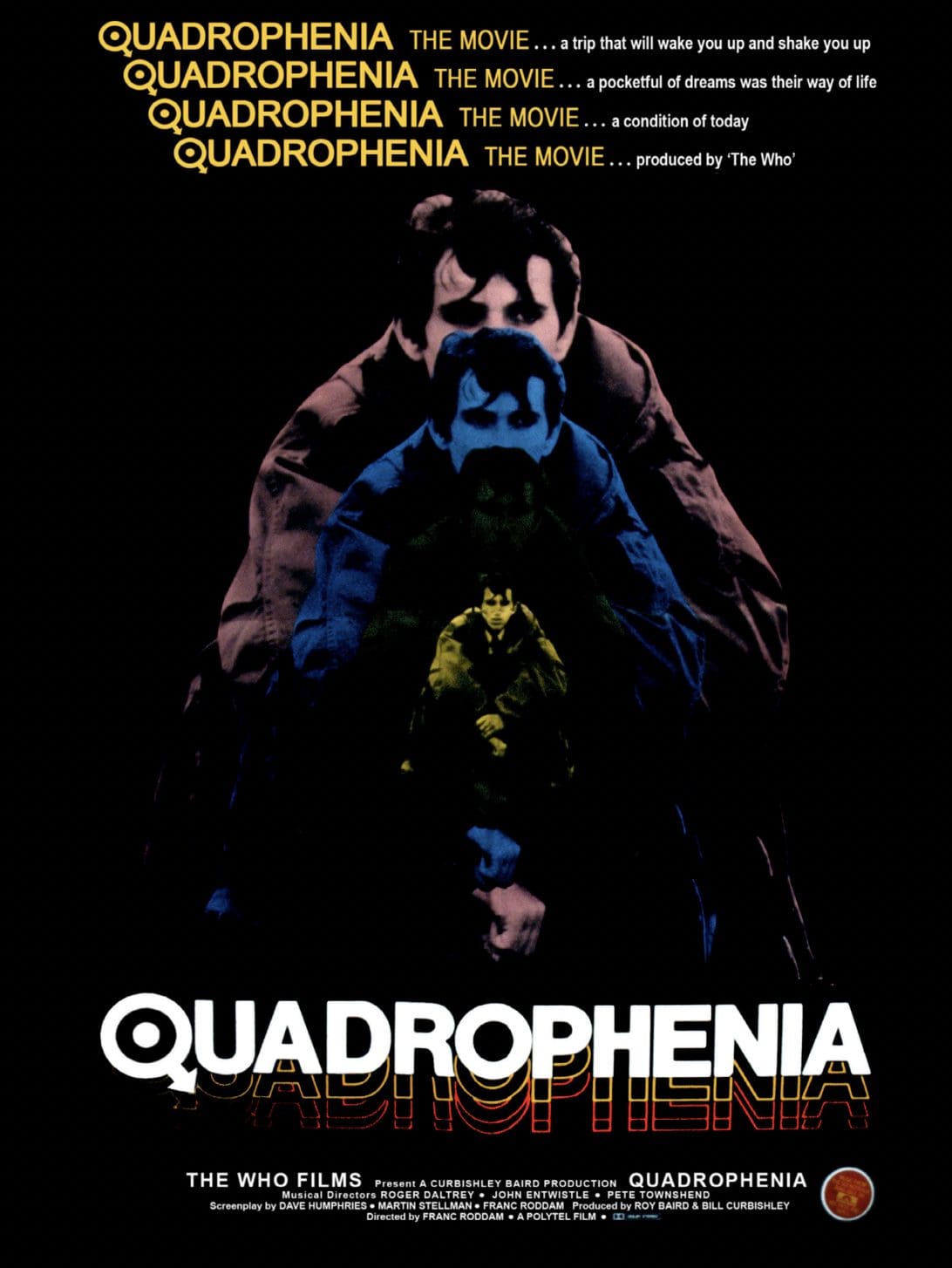

There’s an air of glee in how Roddam, who is speaking to me at his charming West London home (all very minimalist, ‘Scandinavian’ as he refers to it—albeit for a large Arabesque door) reflects on these moments in Quadrophenia. It’s more than a contribution to cinema; the film went on to influence how people at the time dressed, and how many still try to dress today—as the slick, neat Mods: a working-class phenomenon that he explains could only be born from the sixties. But when the film’s premise arrived in front of Roddam, there were trepidations. In the late seventies, youth culture had moved into the Punk era. “I was reticent about making this retro film while that was happening,” he tells me, “but I realized I had a different agenda. It was a story about teen angst in the working classes, and that still felt relevant.”

Originally, the role of Jimmy was offered to Sex Pistols frontman Johnny Rotten: “I thought, why don’t we get to the heart of it? Johnny agreed, he got his haircut and did a test.” Franc recalls an instance when Rotten gave him a shirt, after having a fight with Sid Vicious, in which Rotten hit Vicious with the blunt end of an axe, causing the bassist to vomit all over the piece of clothing. Franc later gifted the shirt to Mark Wingett when the actor threatened to leave the set. “Imagine how much that shirt would be worth,” Roddam says, “but Mark’s mum put it in the wash.” In the end, Johnny Rotten wasn’t to be, and an unknown Phil Daniels came in for the role of Jimmy in a performance that remains his most definitive (if you forget his long stint on TV’s Eastenders or Blur’s ParkLife.)

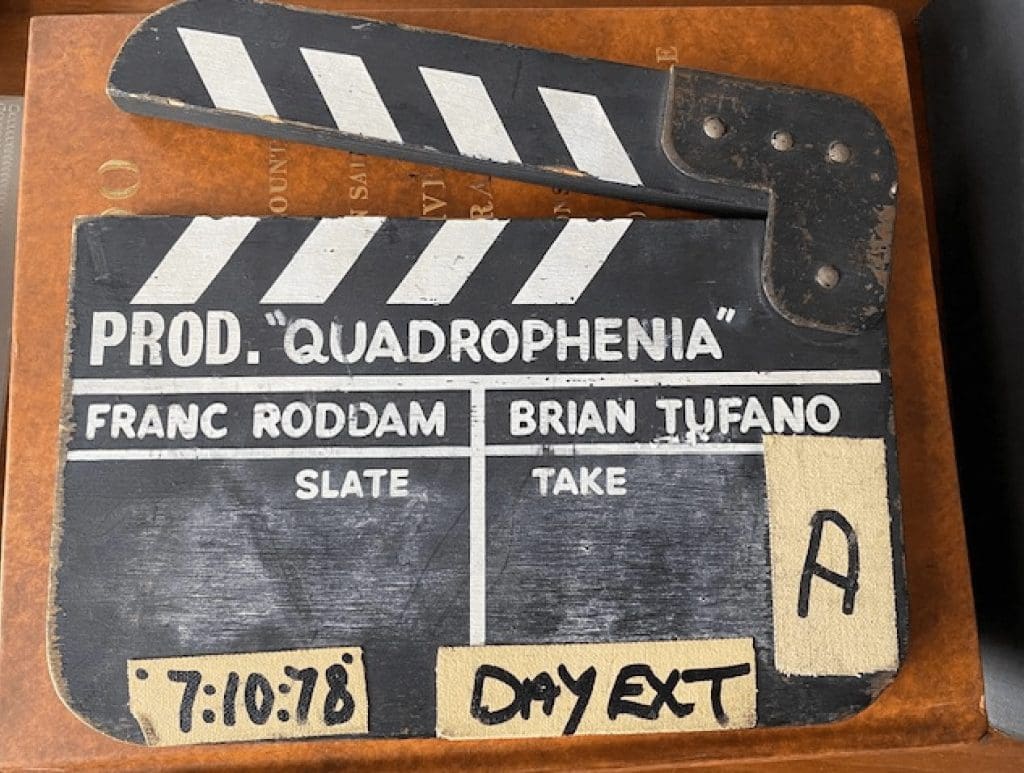

“Phil was brilliant!” He tells me. Franc selected all of his actors on their ability to improvise on the spot; seeking naturalistic dialogue that represented how London’s Cockney working class spoke with each other. “Our screenwriter Martin Stellman is a Cockney, and he knew how to handle the actors, and he had the ear for the way they ought to speak.” When shooting scenes, especially dialogue-heavy segments, Franc would employ camera techniques that he learned in his days of documentary-making to achieve an extra layer of realism. Even in the bar sequences, where Jimmy and his pals hang out before seeking trouble in the streets, the actors’ positioning was meticulously planned like a stage-play, with repeated tales focusing on trial-and-error and composition. “I really wanted the audience to feel like they were in that room, with these kids,” he tells me.

For all of its subtle moments, the film is perhaps best remembered for the battle of Brighton near the end—a huge spontaneous ruck on the beach between the Mods and their rivals the leather-clad Rockers. It was based on true events in 1964, where both groups gathered for a mammoth brawl that made front-page news around the nation. “Fifty-thousand kids just turned up!” he tells me, when he describes that Sunday of shooting. “I spoke to the chief of police and he said it reminded him of the real thing.” Franc’s operation unfolded like the opening of Saving Private Ryan, on the frontlines of Brighton’s beachfront—using a map and walkie-talkies to organize the chaos. “The police offered to help on horseback, but they were making fun of the whole thing and really annoying me, so I told a group of lads to go and attack them, pretending it was part of the scene. They certainly woke up.”

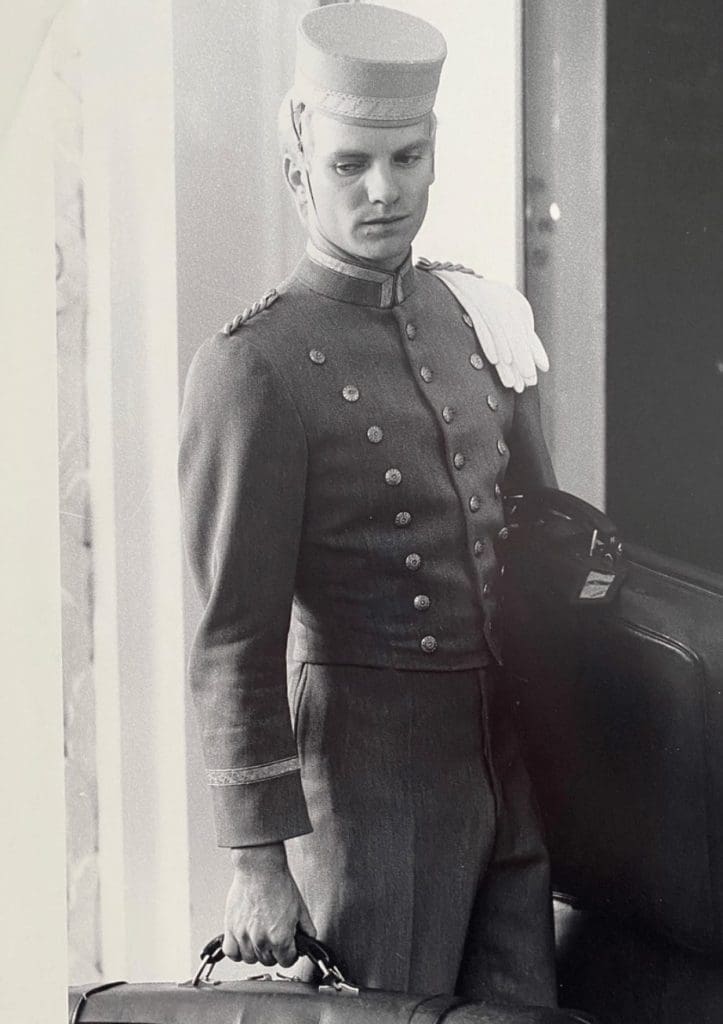

“You killed me scooter… fuck off Mr Postman!” Leslie Ash and Phil Daniels in A RABBIT’S FOOT – ESSAYS & FRONTIERS Quadrophenia (1979). By Franc Roddam. Because of the infamy of the sequence, a number of Brighton landmarks are now frequented by Quadrophenia fans. The hotel where Ace Face (played by Sting) is betrayed as a bellboy is one such spot—it even has a Quadrophenia Room if you’re so well-inclined to spend the evening there—as well as the notorious ‘Quadrophenia Alley,’ where Phil Daniels’ Jimmy and Leslie Ash’s Steph escape to have sex. Fans mark their visit with graffiti (notoriously, ‘Chris from Margate’). “No, I’ve never been to Quadrophenia Alley,” Franc admits, “but I know that the film is special to many people. In Tokyo, there is a whole Mod scene, with bars called Ace Face [after Sting’s character], in San Diego a Mod bar, and in Mexico City there’s a place where they call the film ‘the Bible.’ I think it’s a combination of many strange things for the film to have such a life of its own.” At this point, Franc gets up and approaches his bookshelves, which are a curation of tomes, big and small, and prints or trinkets from his long career. There’s a large coffee table-sized book on Quadrophenia, which has been meticulously researched, as well as—to my great delight—a series of children’s books based on the film: Stinger and Quadwolf (illustrations of bees and dogs from scenes throughout the movie). This is further proof that the Quadrophenia craze manifests itself in the strangest of ways. He recounts another situation to me, more recently, during a Q&A at the Lincoln Centre in New York, following a screening of the film: “I was sitting there thinking, wow, I’m in New York… at the Lincoln Centre, with six-hundred-people in front of me.” But then the first hands were raised. “Somebody goes, ‘I noticed there were two double yellow lines [to prevent parking] on the road in Shepherds Bush. The film is set in 1964, but they didn’t come out until 1965.’ So I replied, ‘What are you? Some kind of fucking traffic warden?’… The audience liked that.”

Why, then, does Quadrophenia still cause such a strong cult sentiment? Why do people still take it so seriously almost a half-century on—even to the point of smugly referring to the British Highway Code? Obviously, I get it. I remember being fascinated with the film as a teenager; as a window to my parents’ generation, who grew up in London on the film’s release, and recount stories of Mods, Rockers, and Skins; and through the cafes and bars that still have something Mod-ish about them in the city today. Although I see Quadrophenia as a quintessential London movie, its appeal to audiences all around the world (and its stamina to continue that appeal) is impressive for a film that is so

Forthright in its portrayal of British working-class culture, but also about the struggle of being a teenager without direction. “I’ve always considered its enduring nature beyond simply the style,” Franc ponders, “I reckon it’s because my film is about a normal person…a loser in life, like ninety-nine-percent of people. That’s universal. It’s very un-American. But very real.”

Franc, inspired by Truffaut’s 400 Blows (also very un-American, obviously), wanted to tell a story about an ordinary guy who doesn’t get what he wants. And at the end, he ultimately breaks down—disappointed by the world he thinks he knows, the friends and role models who betray him; stuck and unable to see another way forward. The ending famously sees Jimmy drive his scooter off of a cliff in hysteria. “I knew you were going to ask me that,” he laughs. “When I first made the film, I imagined he would die, just for the romantic tragedy of it all—like a martyrdom. But no, I don’t think he does now. It’s a metaphorical death. It’s a moment of giving up, and I love that it’s symbolic.”

For years, there were talks about a Quadrophenia Part 2, and even up until last year, he admits, conversations have been ongoing about a much-anticipated follow-up. But for Franc, the story is over—not least because his main cast is now sixty years old or above. “They could’ve made an interesting one like Trainspotting’s sequel a few years after, to show us what happens. But now, I don’t think so.”

Franc had a successful career beyond Quadrophenia. The film was offered to him after his television production, Auf Wiedersen, Pet—a popular comedy-drama that followed British construction workers overseas. “Even I was surprised at how successful it was. But audiences want to see stories about real people,” he claims. The 1998 adaptation of Moby Dick is also a particular highlight, produced by Francis Ford Coppola and starring Gregory Peck in his last role. Franc describes shooting some of the whaler scenes with an excitement and technical wizardry that feels not too far from the Battle of Brighton. But it’s Quadrophenia that remains his enduring gift to cinema. “They’re doing a screening up in Grimsby this weekend,” he tells me, smiling. He shows me the poster, all Mod Cons and sleek, with the sub-culture’s round symbol positioned like a rebellious stamp in the centre. The organisers asked if he could say a few words. “I can’t make it,” admits the Modfather sadly, aware of his responsibility to the film’s devoted audience, “but I’ll do something. I’ll send a video message.”