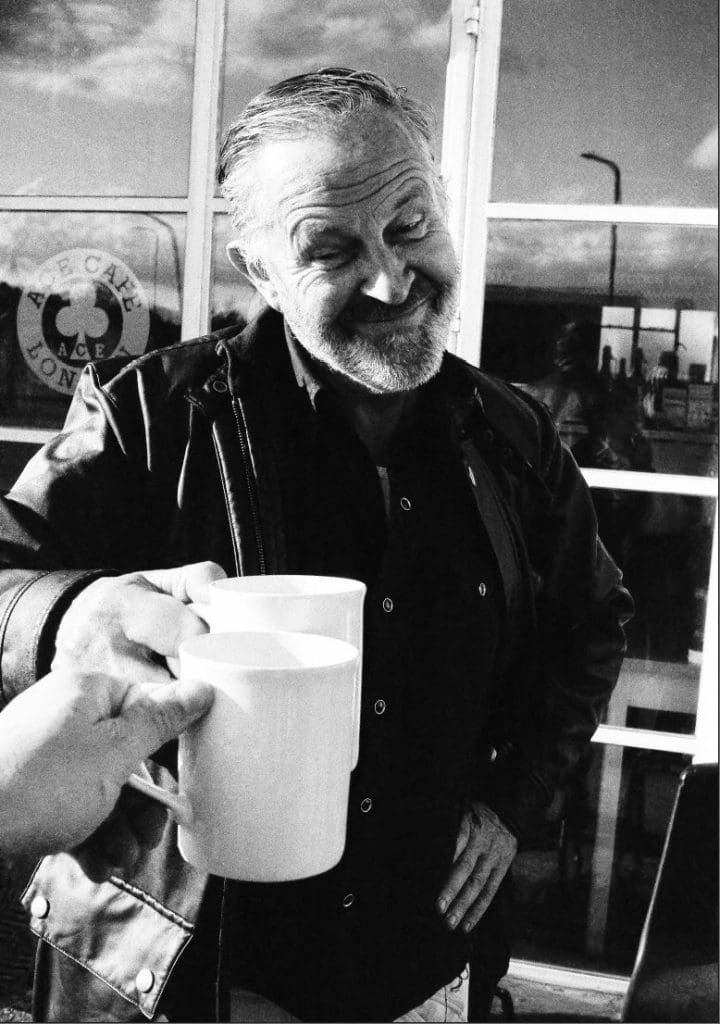

About halfway through my conversation with Nick Ashley, he pauses dramatically and rushes outside. He’s checking on his “dream machine”—a Triumph 500. It’s right where he left it, still gleaming. Only forty-five minutes earlier, the endurance racer, fashion designer, and, above all, petrolhead, had arrived at A Rabbit’s Foot studio, parking his beloved motorbike up the staircase and bursting through the studio doors like a ball of fire.

He walks back to the table, sits back down, and smiles. “Where were we?” I can’t quite keep track, myself. At 66 years, Ashley is a bottomless cocktail of anecdotes, ideas and musings. By this point we’ve already covered Japan (“Japanese people are a lot more sophisticated than us. They were living in cities while we were living in caves. I had one clothing shop in London, and ten shops in Japan. That’s how I made my fortune. With my art, I’m not going to bother trying to sell British paintings to British people. I’m going straight to Japan, where I know they’ll love me.”), the death of the subculture (“Biking was underground until Danny Lyons exposed it. That’s not a good or bad thing, it’s just a thing. I’m not one of these guys who says it was better then and it’s awful now, like an old cunt. It’s just different.”) and regrets; his only one, he claims, is passing up the opportunity to join an amateur punk band that would soon become legendary—a group going by The Clash; you might have heard of them.

Ashley is a man of many hats: he’s run hotels, he’s flown helicopters, he changed the culture of biking through his fashion, he’s just fallen in love with painting, and he’s about to become a grandad. But the big constant for him has always been the wheels and the road. Below, he takes us on a tour of his life and endless obsession with biking.

On The First Bike

I was born in 1957, on a small farm in Wales, so as soon as I could physically fit on a moped, I would ride it to school. At age nine I would ride seven miles to school and back. I never put petrol in it. I don’t know how petrol got in there, but it must have been my father who refilled it, knowing that I was riding completely illegally to school. But he didn’t mind, it was another little problem gotten rid of. I learned to be mischievous and practical and pump a lot of adrenaline through my body from a very early age, and it was a bug that developed into riding dirt bikes around the farm. The second I was of legal age to ride a bike—seventeen—I entered a big two day international race with my brother’s bike. I got a silver medal in that race—it was a lucky one. But that was it, I was hooked, and I’ve been hooked ever since. The moped was the magic machine. It’s hot, it’s noisy, and it’s strapped between your legs. It’s such a powerful thing to have. To have a motorbike in London is like having a helicopter in town. Anyone who hasn’t experienced it is really missing out. I can actually ride a helicopter, but it’s not as thrilling as the motorbike, it’s not quite so immersive. With a motorbike it’s three-dimensional: you’re jumping into the air, you’re sliding, you’re spinning.

On Danger And Dynamism

To know that danger is always omnipresent is a thrilling aspect, but it’s also the dynamism of it. It’s not unlike dancing. When you’re going really fast in the desert, you’re just concentrating on the front wheel, the forks and the handlebars, as if you’re just riding a wheel on a pogo stick. You’re channelling all your energy into that. You forget about the rest of the bike. You’re in the zone, and you’re going so fast that the only thing you can possibly do for survival is to concentrate on that process. In its extremity, it becomes calm. We call it the Art of Grace. It’s as graceful as ballet dancing. You have to do everything precisely, in the same way one would perform a carefully choreographed dance, but with biking, you’ve already learnt all the rules, and now you’re just improvising it at ultra high-speeds. You’re making multiple split second decisions constantly, to survive. That’s the thrill of it. You know you’re thrashing the hell out of your mind and your body and your very essence. It’s a journey into the center of your soul. And you get off that bike and you are fucking buzzing. Even coming in here this morning, I was buzzing like I had a line of coke or something. I’ve also had really fucking miserable times on a bike. Awful times. It’s not all up. And I’ve hurt myself a lot.

On Injuries

The worst injury I had was when I was riding over a hill *on the way* to a race. A sheep jumped out from a bush right in my path. I hit it, flew off the bike with my arms up and broke both of my wrists and my thumb. I was stuck in the middle of the hill, so I picked up the bike with my elbows, kick-started it, got it into gear, had the throttle on my forearm, and rode back across the hill to my sister’s house about five miles away, got into the yard, leapt off the bike. She said I was as white as a sheet. But I made it. Not to the race, but I made it. About a month later, I was asked by a midwife to cross my plaster casts and she lowered my newborn daughter Edie into my plaster-casted arms. That was the first contact I had with her. She’s a petrolhead as well. She loves that story. Plaster-cast junkies, the both of us. With motorbikes, if you’re not falling off, you’re not trying hard enough. You can cruise around and never part company with the bike. But that’s not going one-hundred and ten percent…it’s merely going one-hundred.

On Winning at The Dakar

That was seventy five percent. In the year 2000 they did a celebration event which I had spent years qualifying to do. It was Dakar to Cairo, Senegal to Egypt. All across the Sahara. We did Dakar, Porotania, Marley, Burkina Faso, Nieje, Libya, and Egypt, in two weeks straight, 14,000km. But I wasn’t entered to win anything, I was entered to finish. So I watched my Ps & Qs, and at one point I was told to speed up. Everyone else in my class fucked up—they were going too fast and they wiped out. They thought they were racing. But for me, I was just taking myself on. It’s a fucking difficult event, and I wasn’t going to bugger it up by trying to beat other people. So I carried on at my little pace, and everyone else wiped out except for the Spanish champion who beat me, and I came second. Podium finish. Silver medal. My feet haven’t touched the ground since. I was telling my daughter the other day “if I die tonight, I’d be lying in my grave thinking “fuck me, Nick, you really fucking nailed the Dakar, you really did fucking nail that.” She said, “You can’t die tonight,” and I said, “Why not?” She said, “You have one more thing to do in life: you have to cross your arms, again, and I’m going to drop a grandchild in there.” Well, fuck, I gotta stay alive, don’t I?

On Camaraderie

I’ve always been a lone wolf, and always found camaraderie a bit of a difficult thing. That’s why I love endurance racing. I’m out there by myself, doing something really dangerous at a high speed. But I’ve got my shit together. That’s where my sweet spot is. That’s where my motorised meditation is. I’m not a team player. I’ve got a thousand acquaintances, but only a tiny handful of best friends, who are all individual people. I don’t have a gang of boys I meet down at the pub on Friday night. If I did, I wouldn’t turn up. I’d probably be at Kew Gardens getting carried away looking at flowers or something. I’m in my own world.

On Off-Road Riding

I’ve done enough off-road trail-riding to have circumnavigated the globe twice. Six months ago I got hold of a 700CC modern adventure bike, and I went from Wales to Gibraltar. I rode via Northern Spain, where I picked up a group of twenty other lads from all over the world. We rode together, a gang of us, through Portugal, sleeping in tents at night and taking beautiful old off-road trails, going village to village, getting into rivers with all of our gear on just to cool off because it was so hot. The group was called El Solitario. Anyone who knows about high-end biking will know that El Solitario are the leaders of it—they’re the Spanish playboys. We were doing it outlaw style, and we were invincible.

I’ve ticked the bucket list so many fucking times, I don’t know what’s left. It’s not where you are, it’s where you’re at. It’s not like I have to do a dream trip on dream bikes. I could be riding on a moped to Marrakech and it could be a dream trip if I make it so. I like improv. I like the state of mind. I’ve not done an awful lot of riding with my brother, because he doesn’t race so much. He taught me how to ride a motorbike, but he’s got a lovely adventure bike. And he suggested that he and I take our bikes off-road to a film festival in Italy. Not a gang. Just me and my brother. Is there anything better than that? We’ve both worked so hard all our lives, we’ve got kids, we’re about to become grandparents. It’s the perfect time. And I absolutely don’t give a shit what I’m riding. Though I happen to have the perfect bike for the occasion—a Yamaha Tenere 700. We’re going to travel super light, just the clothes on our back. We’ll sleep rough. Neither of us mind bathing in a river. It could be a great trip. I can get to know my brother like I’ve never known him before, and I’ve known him for 66 years. We both love each other, but we’re busy getting on with our own shit.

On Mortality and Regret

When I was in my 20s, I never thought I would make it past 30. As soon as I was old enough, I got out of Wales and came down to London and went to Holland Park comprehensive, a fabulous school. And everyone there was just living this mad fucking crazy life. Drugs, parties, sex, rock & roll, and motorbikes. Anything and everything fast and furious was being consumed. Then punk came along and ramped it up. None of us actually thought we’d make it past 30, and a lot of my friends didn’t, a lot of my friends are dead. A lot of it was overdose, whether it was intentional or not.

Personally, I only have one regret in life. St. Martin’s school of fashion was a massive deal for me, and the second I got in, a friend of mine invited me to join his newly formed Punk band as a drummer. I didn’t know how to play drums, but he said, “I’ve seen you dance, you’ve got rhythm and you look cool, it’s a punk band.” But the lifestyle, I said, you’re going to be going up and down the motorway in a transit van, and I’ve only just gotten into this amazing school. I told him sorry, but I’d have to turn him down. It was Joe Strummer from The Clash.

On Changing Biking Style.

It took me quite a few years to start designing my own motorbike clothes, which happened when my mother died—I left the family business and started my own. I wanted to do men’s clothes, but men’s clothes that were very personal to me. I wanted to make something that was multifunctional. I think people buy way too much gear. It was in ‘92 when I started, and rampant consumerism was getting out of hand, people had just started getting into disposable fashion. So I thought, why not make a jacket that can be really good on a motorbike, you can use it for skiing, you can wear it to work, you can wear it to the weekend in the country, you can take it down the pub—and you can wear it for years. You can maintain it, and It’ll get you laid, it’ll be that cool. And when you’re finished with it you can pass it down to your son or daughter. There are people who actually did that, and now the next generation are wearing my stuff. It actually happened. The trouble with that business model is you never get a repeat customer [Laughs]. The product is that good. All of my motorbike clothes in those days, when you wore them, just screamed “I am a Biker”. Bikers in those days really were second-class citizens. You were definitely working class. You were a rebel and considered the lowest of the low. If you arrived somewhere on a motorbike, you’d be hushed to the side: an undesirable. I wanted to change that. I wanted to make clothes that you could arrive to a film premiere wearing, and not be told to fuck off. My highest point was Daniel Day Lewis arriving at the Phantom Thread premiere in a Nick Ashley waterproof black tie. He arrived at the premiere and the security guy said, “Sorry, sir, but there’s a premiere going on.” And Dan unbuttoned and exposed the tie, and said, “It’s my premiere.” And they parked his bike for him and he went in. How about that?

On Friendship with Daniel Day Lewis

Daniel’s the worst best friend I’ve ever had. He’ll ring up one minute and say “hey Nick, how are ya boy?” and it’s fucking Lincoln. And the next minute it’s some fucking Irish cunt. [Laughs] He really does stay in the character, it’s so annoying. I once stayed with him in his house in Ireland—the front door had a letterbox with a thousand rolled up scripts cascading down into a mountain on the floor. I said, “Dan, don’t you have a film script reader?” He said, “No, I don’t bother at all—they’re all shit.” He’s fussy.

He asked me a few years ago to be in The Phantom Thread, because it was a good excuse to hang out. I played a photographer called Charlie. It was all improv. I think he had a bet with Paul Thomas Anderson about nature vs nurture in acting and whether you had to be trained to be a good actor. And Dan knew I would be straight with him. I taught him how to ride a dirt bike. I’ve known him since he was 14. I’d tell him to fuck off if he deserved it, and him the same with me, but him more so, because he’s a cunt. Anyway, we did a few takes, and at the end Paul came running up to us with his arms thrown high screaming, “That was amazing!” and he goes over and hugs Dan. Excuse me? I’m not even a fucking actor, I’m fucking dying here. He was like, yeah, alright, whatever. But I loved it. I’m hungry for more of that.

On The Movies

On Any Sunday, featuring Steve McQueen. He wanted to make it so he could share his passion for motorbikes and how beautiful they were. My father took me to see it, in his Ferrari—a true petrolhead father and son experience. He took me knowing I would get the bug. It was like taking twenty magic mushrooms and losing my virginity all in one. That’s what the film was to me. McQueen rode a Husqvarna 250, with Mert Lawwill and Malcolm Smith, who were the top riders in the world at that time, and McQueen himself was 10th best dirt bike racer in America. He was the real deal. Everything I’ve been talking about has been visualised in that movie. It’s not a laddish film, it’s not like Danny Lyon’s book. It’s about motorised human beings, and the fabulous feeling you get when you’re on the edge. It’s the only biking film that has hit the spot for me, and still does.