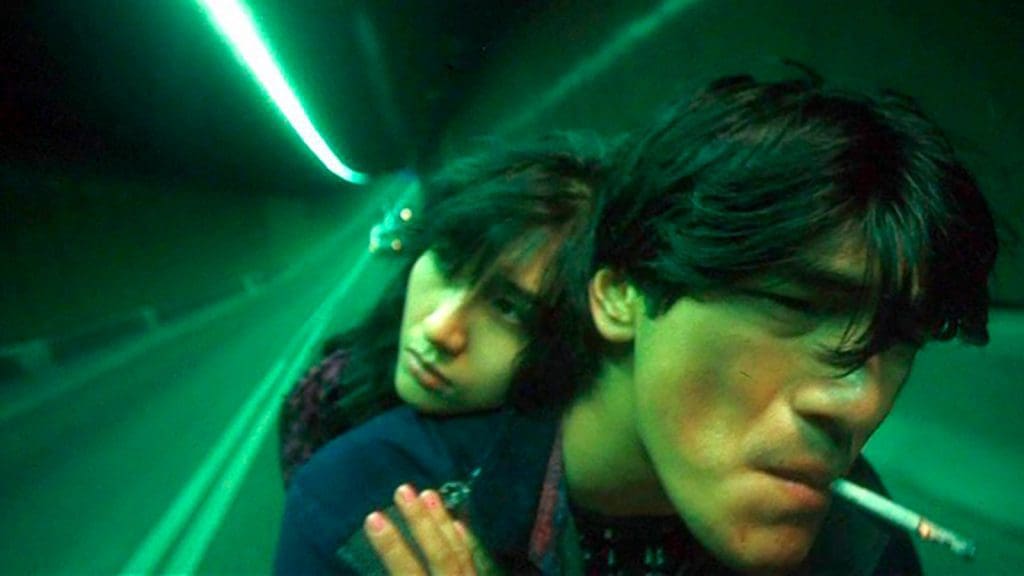

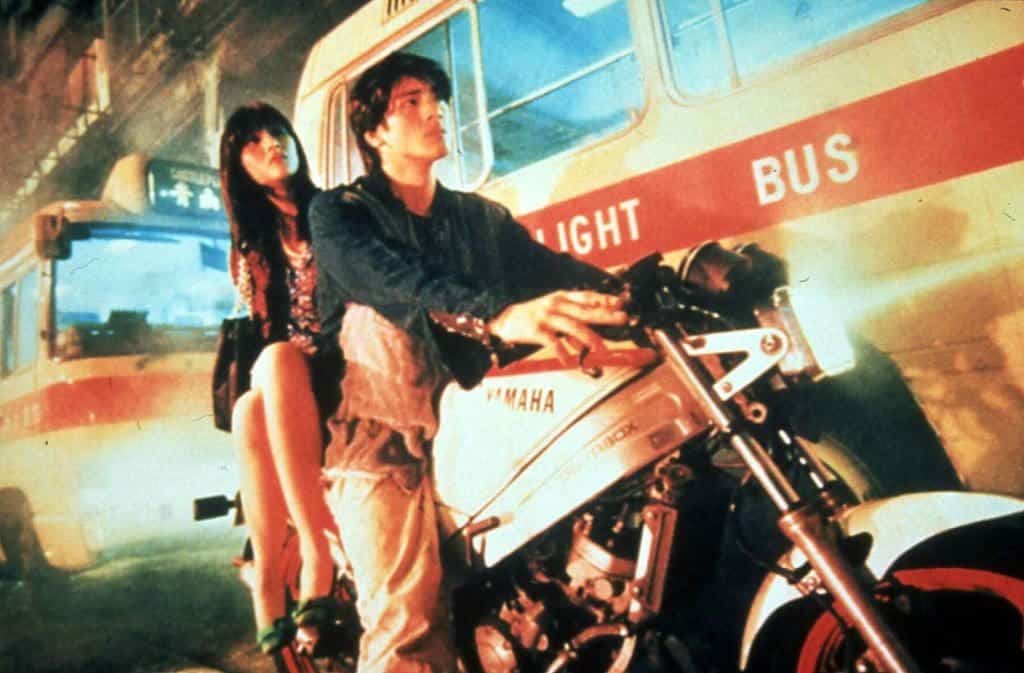

The Yamaha TZR128 1988 zooms down Hong Kong’s emerald-lit Cross Harbour tunnel. On top of the motorbike is Takeshi Kaneshiro’s mute ex-convict Ho Chi-mo. Just behind him, wrapping her arms around his chest and resting her cheek on his shoulder, is an unnamed hitman’s assistant (Michelle Reis). The film is Wong Kar-wai’s Fallen Angels, the moodier younger sister of the Hong Kong filmmaker’s classic Chungking Express, which he had released only a year earlier. Like Chungking, Fallen Angels is told through two intertwining stories. The first: of the aforementioned hitman (Leon Lai) looking to start a new life, and the secret infatuation harboured for him by his “agent”. And the second: of Ho Chi-mo, the eccentric mute on the run from the police, who falls in love with a love-scorned woman (Charlie Yeung) that he meets at a noodle bar.

While there are some delightful parallels between Chungking and Angels, the differences are night and day. Where Chungking Express has prime pixie dream girl Faye Wong dancing spiritedly to her own cover of The Cranberries’ Dreams, Fallen Angels sees a devilishly sexy Reis caressing herself on a jukebox as Laurie Anderson’s avante-garde track Speak My Language vibrates through its speakers. If Chungking Express is about heartache under the bright lights of metropolitan Hong Kong, then Fallen Angels is about the loneliness and longing living in its shadows— and fewer films have made isolation so intoxicating.

Since the release of the film in 1995, this particular scene on the Yamaha has become a staple of Wong Kar-wai’s iconography (along with pink rubber gloves, cans of pineapple and toy planes) and you’ll see it plastered all over Fallen Angels’ promotional material.

It’s no coincidence that the film’s soundtrack features a bonus track—Go Away From My World—by the Girl on a Motorbike herself Marianne Faithfull, a crafty homage by Wong (whether the title of his first movie As Tears Go By is also a tribute to Faithfull remains to be seen). But even more impactful is the visual aesthetic that the sequence, and many others throughout the film, are intrinsically tied to. It makes Fallen Angels not only one of the sexiest movies to be put to screen, but among the most melancholic.

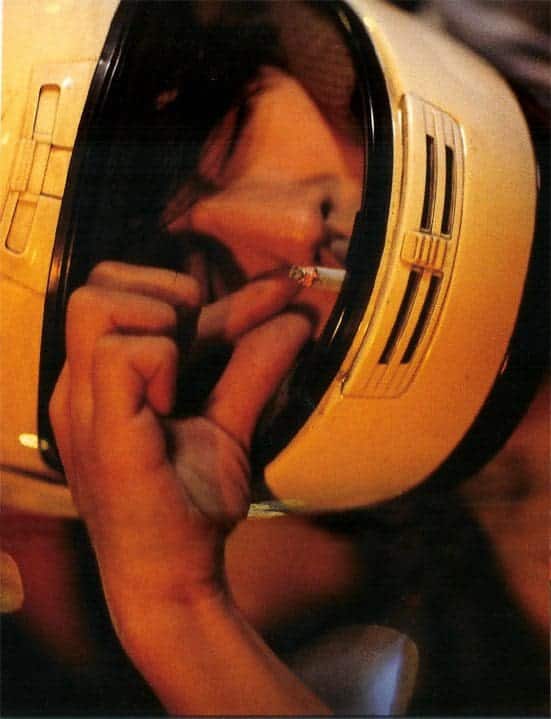

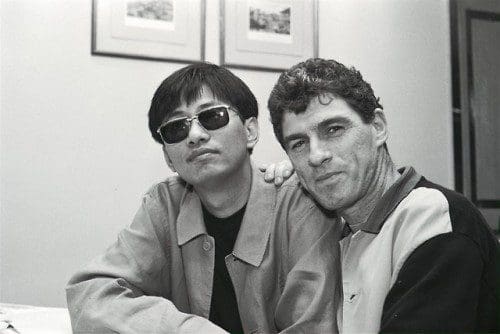

Director Wong can’t take all the credit for bridging the gap between those two moods, which just as much belongs to the camera itself, and the man wielding it: Christopher Doyle, Wong’s frequent collaborator, who is behind some of the most gorgeous shots in East Asian film history. Aside from Wong he’s worked with Fruit Chan, Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, Zhang Yimou, Edward Yang, Chen Kaige and Stanley Kwan. Though his connection with Wong remains a thing of pure electricity, and Fallen Angels is their pièce de résistance. The visuals of the film are characterised by Doyle’s kinetic, almost jazz-like pace, and the intimacy he creates between the lens and the actors, a technique he once described as a dance between himself, the camera, and the subject.

The lens Doyle used to achieve this intimacy was for a long time something of a mystery, but, after some expert sleuthing by YouTuber WatchingTheAerial, it was unearthed that the miracle gear was a Century Tégéa 9.8mm T2.3 with a 7X wide-angle attachment, which provided the cinematographer a 6.8mm depth of field. In other words: he used a wide angle so extreme that it was almost unheard of. The view was so wide that it captured the entirety of the cramped teahouses, bars and apartments featured in the movie, and it kept the actors up close and personal while simultaneously distancing them from every other aspect of the frame. In an interview with Positif in 1997, Doyle said, “With a 6.8 I can see my assistant standing next to me. So the characters have to be very close, because as soon as they get a little further away, they seem too far away.” The lens was reportedly Wong’s idea, considering the use of a regular wide angle lens “too ordinary.”

The impact of the film, and the crucial shot of Kaneshiro and Reis on the Yamaha, isn’t quite the same without Doyle at the clutch. Its legacy is meteoric—the aesthetic that influenced a generation. You can see Doyle’s mark on underground photographer/videographer Jason Isip, who channels Fallen Angels’ melancholy by playing with grunge-filters, fish-eyes and handheld digital camcorder. It can be seen in W Korea’s recent shoot with Burning actress Jeon Jong-seo, which references the aesthetic and has her clad in angel wings. It’s no secret that K-Culture is enamoured with the WKW aesthetic: just check out the music videos for Mamamoo’s Wildflower, Suzy’s Yes No Maybe and several of girl-group Loona’s tracks. Click through pinterest and tumblr long enough and you’re bound to find an endless horde of both ancient and active moodboards mimicking Fallen Angels’ dreamy visuals, deep colour palette and extreme wide angles. Hop on Instagram and use the filter literally titled “dir. Wong Kar-wai” that soaks your image in a neon-tinted green. Perhaps the most tawdry display of this influence is by The Chainsmokers, who directly reference the Yamaha shot on the cover of their 2023 album Summertime Friends. The list goes on.

The impact of Fallen Angel’s visual tone isn’t built on sex and style alone (though that is a contributing factor). When all’s said and done, Fallen Angels is a film about the detached. The shallow depth of field, often paired with either time lapse or slow-mo, that Doyle and Wong use to shoot their actors creates a feeling of disjointment between the characters and the world passing by around them. The protagonists almost never talk out loud—Ho Chi-mo is mute after experiencing heartbreak (he claims he ate an expired can of pineapples, but fans of Chungking will know what that really means).Instead they monologue to the audience in voiceovers. They’re caught in stasis, longing for connection but a little too out of sync to attain it. More like ghosts than angels, it comes as no surprise that many who live and breathe the digital land of the detached have adopted the aesthetic, subconsciously or consciously, as a way to express their romanticised loneliness. In The Mood For Love may be the Wong/Doyle collaboration that has influenced on the largest scale, but the impact of Fallen Angels is on a different plane entirely, coded with the dissociation of a generation.

The impressionistic colours and artificial lighting of Fallen Angels similarly work towards establishing this place of permanent yearning, a limbo state that you want at once to revel in and also escape. Doyle, who is a white Australian, but has been associated with Taiwan and Hong Kong since the ‘70s (and has been given his Chinese name Dù Kêfēng, meaning Like The Wind) said in an interview released on the Criterion remaster of Fallen Angels, “My job is about giving colour to emotion. Colour is subjective and changes based on emotional response. Most of Western colour theory is in line with Western philosophy…in our world [Eastern], how we light a scene, how we filter a scene, what film stock we choose, is very much about a very individualistic and personal response to how colour is in our lives at that moment.” In the closing seconds of Fallen Angels, Ho Chi-mo reaches the end of the tunnel, still riding the Yamaha TZR128, the unnamed woman still clutching his chest. As The Flying Pickets’ Only You steers the movie to it’s final frame, the camera pans up to reveal daylight—natural light—for the first and only moment of Fallen Angels’ runtime, suggesting that if what Doyle says is true, then there’s yet some hope for our hotblooded, alienated angels after all.