“In time things part; in space, things touch.”

E.M Forster, A Passage to India

Tracking down Peter Frankopan, even once, takes time. When I first spoke to the Oxford-professor in 2015, it was in a rickshaw in Jaipur; the ‘Pink City’ of India, en-route to a seminar in a Mughal castle. Tall and raffish, the Oxford don had become an unlikely literary rockstar with his second historical epic The Silk Roads: A New History of The World: a retelling of the historical world-order that cast the Middle-East and Central Asia as “the crossroads of Civilization”. To Frankopan, it was the hub of all trade; the hidden engine of the world; and a forgotten heart he had traced his finger over through maps since he was a child.

Eight years on, Frankopan is book-touring for his new magnum-opus: a history of humanity’s relationship with climate-change called The Earth Transformed: An Untold History. Tired, Frankopan is grateful for letting him off the hook for our original talk the week before (so he could watch a Wimbledon match he said was “rather mediocre in hindsight”). In an attempt to enjoy the hottest month in human history, I meet Frankopan for tea on the rooftop of the London restaurant Tattu. After three books, I’m keen to talk about his latest, but Frankopan appears unchanged: rolled-up sleeves, open shirt, ruffled hair and beaded jewelry. And still radiating the same schoolboy-like kindness.

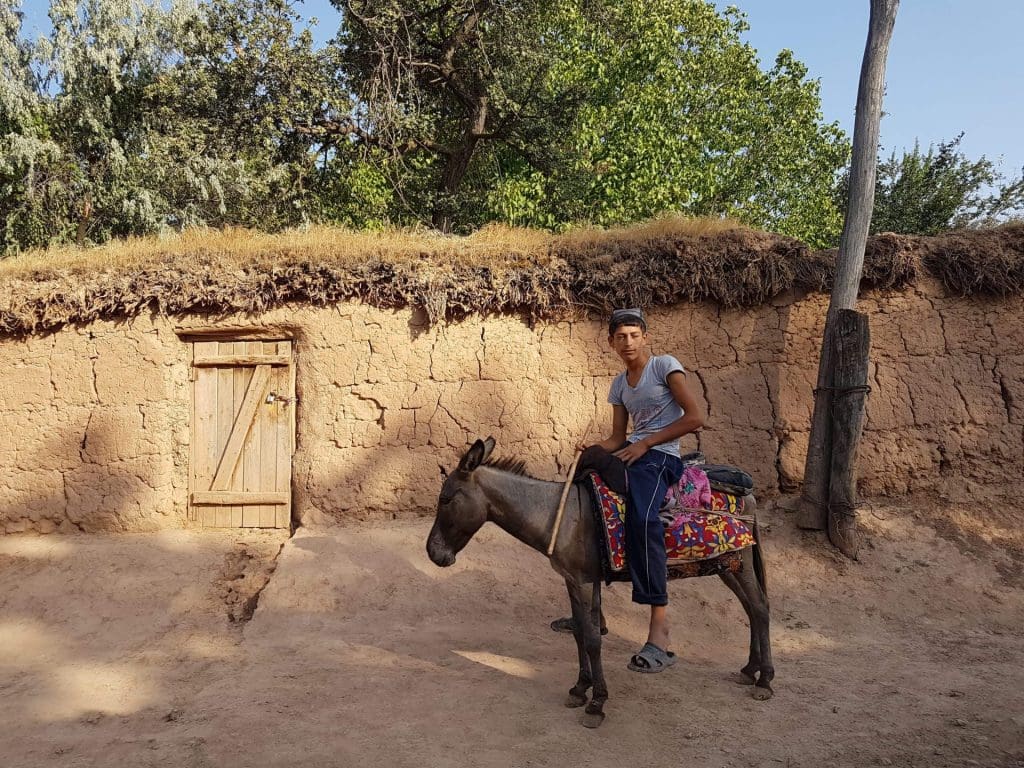

“What did you do after that taxi?” he asks immediately. I pull out my journal and trace my route through India; then my degree in Ireland; and explain how reading The Silk Roads led me through Central-Asia in my final summer in college. It was there, chasing the ruins of the Timurids, that I “nearly got my head blown off at the border of Afghanistan.” I tousle my hair for show. “So you used your time well,” he remarks cooly. Our waiter takes our order, and we turn the clock back again.

It is hard to imagine Frankopan ever being surprised—but after an unorthodox Byzantine account of the First Crusades written in 2012, he never thought his second historical book would bring such attention to a somewhat unnoticed part of the world. “I’m an academic, my job is to research and write, not think about who might read [The Silk Roads]…but I wasn’t expecting it to have such an impact.” He admits the needle drop was at the Jaipur Literature Festival that year we met—an “incredible place”—after Colin Thubron had first reviewed it positively for the New York Review. With the legendary travel writer praising in his article how “connectedness becomes almost its leitmotif,” Frankopan was introduced to the festival’s main-stage.

The roar of the crowd in India in 2016 was the “record scratch” moment for him—enough to walk back off the stage and back on again, having told the audience he wanted to video the reaction to show his young children he wasn’t wasting his time. I remember seeing him from the crowd, and I ask what drove that fervor around the world; especially outside of Europe. Visually, he says, the book got things right. The design was almost a disaster: a front cover with a mockup of a dump truck and a King Darius-like Persian relief. The final swirling imagery was designed by Emma Eubank after Peter suggested the interior of the Jameh Mosque in Isfahan: an abstract invitation to readers which Frankopan calls the “exactly right key” for the book’s universalist tone.

The focus on the world beyond Europe and the west was also well-timed; in a changing world where many were predicting that this will be the ‘Asian century.’ Then there was China. “I got lucky that it came out at a time where China was just starting this Belt and Road Initiative. To the Chinese, the idea of what the Silk Roads meant wasn’t really a foreign thing…but all over the rest of the world, we suddenly had to realize the world was changing. I mean, The Silk Roads came out six-months after Russia invaded Ukraine. So there was the idea that all these faraway connections that few paid any attention to really mattered—not just in the past, but in the present and future too.” A keen sportsman (even briefly representing his Croat national cricket team) Frankopan follows up with the example of Abu Dhabi’s sovereign wealth fund buying Manchester City that year. Or the rapid changes in India, Central and South East Asia. “The world’s changing and we in Europe, we were in a position where we hadn’t studied anybody else when we thought about history. So I was lucky with timing.”

Luck seems relative. I ask if it was part of a rude awakening for European readers and Frankopan—a habit which I’ve noticed in other interviews—circles around my question politely. “I don’t know about that. Once you release a book and people start to read and engage with it, it’s out of your control…but I can tell you I used to go for a coffee with people and talk about how I was writing about the rise of Islam, the codification of the Qu’ran, or the stuff you were talking about with Timur…now people, their eyes wouldn’t necessarily glaze over, but they’d look panicked, and often try to rustle up something from the deep recesses of their mind some random fact about the Byzantines or the Abbasids. Then the conversation would move on very, very quickly.” I wonder if this is part of the reason why his history is so often ‘new’. Frankopan’s history books focus on exchanges, from economic to linguistic, religious to genomic. The Silk Roads and The Earth Transformed could each be described as studies of networks and the flow of material and ideas he describes as “a history of connections and exchanges.” True to his easy-going personality, he humanizes that science, taking disparate pieces to create a virgin thread that explains people, cultures, empires, oddities. The result is Frankopan weaves what should be the faraway details, and makes it feel intimate with your own life. “Your work always reminds me of traveling,” I tell him with a smile.

There are parallels in that journey in space and time. When a historian brings things together, Frankopan explains, they must “go to primary sources…they must let the voices from the past explain what they were seeing…to let them sing and speak.”

I ask how he reduces global history to five-hundred pages; a feat he’s done twice-over. It’s “daunting” admits Frankopan with the same British cool. “There is no point telling people what they already know,” he explains, “so the challenge is to be engaging but also to lead the reader through into new worlds that open up new perspectives. It’s not easy, but then why should it be?”

Our drinks arrive with a clink. It’s two cups from either side of the world: flat white coffee, for Frankopan, and green tea for myself. So is connecting it all this great chore? “It’s just what I have to do. It’s a total joy. I’ve spent my life thinking about the past.” The trick is to love it, he explains. Find what’s interesting, then share that enjoyment: that’s how you communicate the importance. A polyglot, Frankopan read through dozens of languages for The Silk Roads and far more for Earth Transformed; in the past, he has translated perhaps the most famous of all Byzantine texts—The Alexiad of Anna Komnene—for Penguin Classics. The breadth reflects his works’ global outlook, but also his personal touches towards adventure. “I had a Russian teacher at school—I was very lucky to have a Russian teacher—but he said, ‘if you want to know what people are thinking don’t just go read The Times, or The New Yorker, go stand in a bar on Friday night and hear what people are talking about. Learn the songs that they sing; learn how they tease each other.’” The point, he explains, isn’t the quantity of languages but the quality of its connection. “Don’t be scared of going into new regions and periods and just learning.”

That process was instrumental to The Earth Transformed. The book builds on his work on connections between Asia, Europe and Africa but goes even further: his journey through climate change making him study the ways that the natural world has shaped human history, and how our species has shaped the environment, including global warming and climate change. “It was a thrill to work on parts of the world that I’d never properly worked on before. Of course that means getting up to speed with vast research fields and not only working through primary materials, but on the latest, cutting-edge research being done by historians, scientists and scholars around the world.” I ask him if he thinks what he does is hard. “I am a historian,” he says, “not a doctor in A&E. So no; it’s challenging, but people’s lives don’t depend on what I write.” He looks at his coffee. “I think what I do is important; but academics can sometimes take themselves a little too seriously.”

I tell him he has a gift for taking people to places—and opening minds. Frankopan smiles: “All I’ve done is introduce you to the people who took me there. It’s as if those people are my extended friendship group—my pals, some of whom have been dead for two-thousand-years—or more. You know, there’s that moment when you read something written so long ago that it sings in the page and makes you laugh or wince.” I compare it again to traveling, to getting in a taxi in India, to the advice of his Russian teacher: searching for that authentic connection. To Frankopan, he can’t help but see these past people as woven to the present: “What were they thinking? Were they at their wits end? Did they know they were going to be read in a hundred years?”

A conversation with Frankopan can feel like free-wheeling through history; a butterfly effect where little details compound into centuries. My choice of tea triggers a lecture on the rise of the British Empire, then how the cavernous geography of our southern coast was a smuggler’s paradise for sailors. He begs the question: when you have a cultural legacy of hiding your footprints while you trade, is it surprising that the five biggest tax havens are British dominions? Did you know the potato’s introduction in Europe boosted calorie consumption and lessened foodshock? That a small brown crop from the Americas drove urbanization? Destroyed Ireland?

Given the dark cloud of climate change hanging over the end of The Earth Transformed, I ask Frankopan if he’s a pessimist, and he admits he’s often asked this: “Optimism and pessimism are misleading bedfellows…they’re asking how do you feel emotionally rather than clinically?” After the Berlin Wall fell, even as an adult historian, Frankopan says he’s “still struggling to understand” how we’ve come from thirty years of “eternal peace” and the promises of global trade to “a world which looks like dusk in the Savannah.” “Predators are out,” he tells me sipping coffee, and it’s no longer dangerous states but a hydra of “corporations, natural events, climate changes and new technologies.”

The ending of Earth Transformed doesn’t exactly suggest a rosy outcome: Frankopan warns that with a free market opening up the world’s resources at a global scale, he doesn’t “bet” on us managing climate change without major human suffering. I feel burnt alive by an English sunset today, but Frankopan looks past his empty coffee, still energised. I remind him we’ve just experienced the hottest month in human history, and he tells me, after citing a soil temperature reading, it’s “like watching a car crash in slow motion.” I finish my green tea. There’s a sense, sadly, of things coming to an end.

“Do you think history can inform our politics?” I ask the question almost bluntly as the waiter takes our trays. Frankopan doesn’t like these questions, but I press: “Your work so often goes from the past to the present…It’s impossible not to look at your works politically.” As we walk, Frankopan says a historian can only tell us how we got here. I laugh when he tells me that historians also often predict the future wrong compared to other academics. It’s the same schoolboy grin by the door. The drive for a historian shouldn’t be answers, he smiles, but good questions.