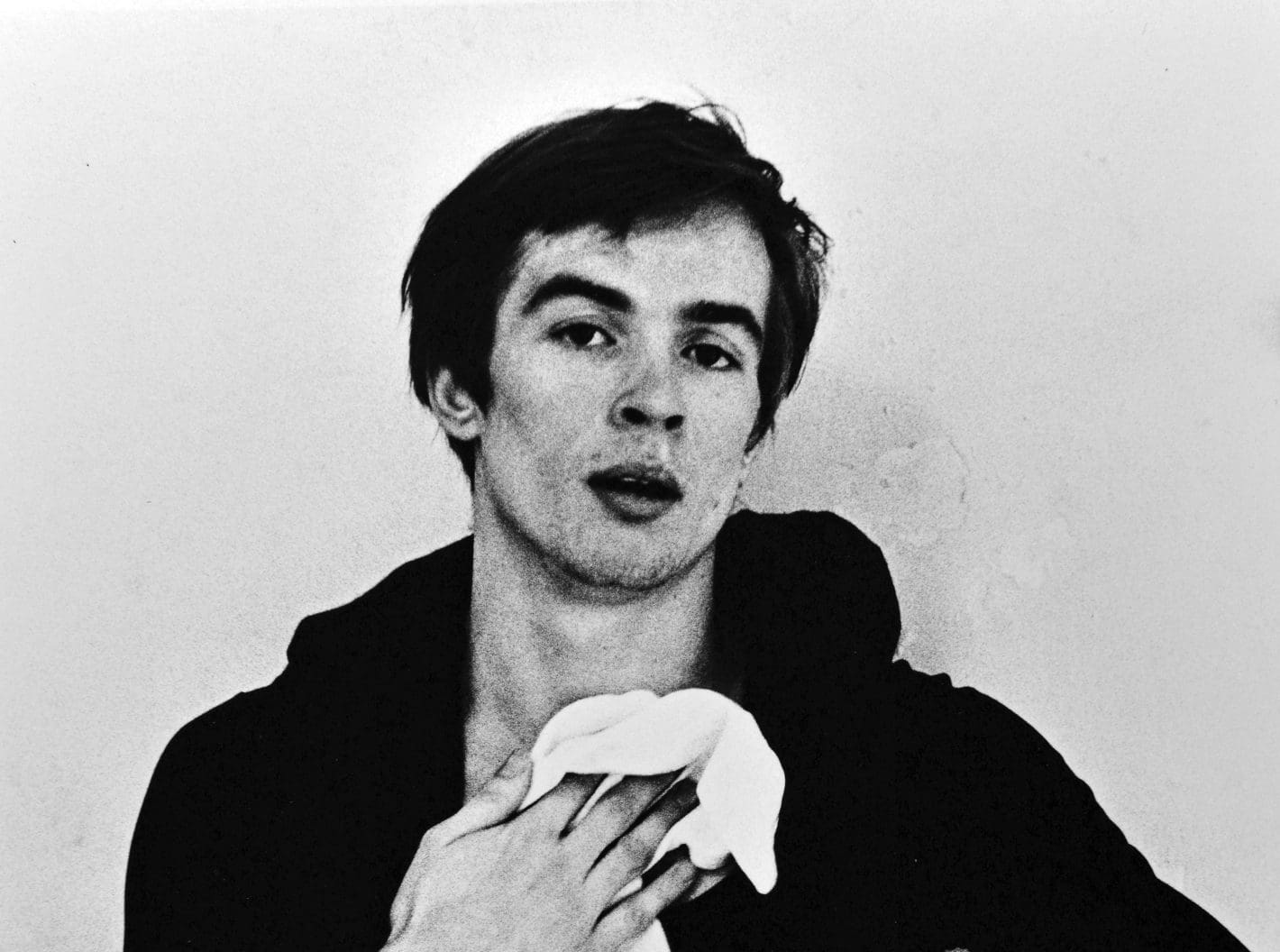

It was at the height of the Cold War, while the world teetered on the brink of thermonuclear disaster, that the Soviet Union presided over a decision, which would ultimately change the face of ballet, and the perception of male dancers, forever. The question that the KGB operatives faced was whether to permit the Kirov Ballet’s star attraction to be a part of the company’s European tour. After all, said attraction was a known rebel, who was already gaining a reputation for promiscuity, having had an affair with his ballet master’s wife, a woman twenty years his senior. But the Soviet Union was determined to demonstrate their country’s cultural supremacy over the West and classical ballet had long been considered their most powerful propaganda tool. Essential to that supremacy was Rudolf Nureyev.

A decision was made accordingly, and the twenty-three-year-old dancer set off for Paris, under the watchful eye of the KGB. Nevertheless, on being released into the throes of Paris nightlife, Nureyev broke all the rules. He mingled with foreigners, embedding himself in a group of glamorous Parisian socialites. But more alarming to the agents watching, were his frequent trips to the city’s gay bars. Eventually, he received news via the company that his mother had fallen seriously ill, which he instantly spotted as a lie, having spoken to her the previous day. He refused to go home, for not only did he fear that incarceration awaited him, but never again did he want to give up his newfound social freedoms. When he arrived at the airport to travel on to London with the rest of the company, he was seized by two men who were to forcibly return him to Kirov. But, by a stroke of luck, the French ballet critic Olivier Monde was also awaiting a flight and made a swift call to Nureyev’s friend, Clara Saint, a Chilean heiress who was rather helpfully engaged to the son of the French Culture Minister. She turned up at the airport at 5am, in slippers and a nightgown, and persuaded the French police to aid her in rescuing Rudolf Nureyev.

Thus, the Soviet Union’s star attraction was granted asylum in France. From that day on, Nureyev would traverse the world in the manner of one of the wild animals he was so often compared to, marking his territory by way of sex or notoriety and even staking his claim by purchasing property all over the world. The multiplicity of his sexual affairs, his decadent behaviour, his temper and disregard for authority earned him a reputation as something of a gluttonous, philandering bad boy. But a closer look at the man who was prematurely ripped from his home and cruelly forbidden to see his beloved mother and sister for what would turn out to be thirty long years, might suggest that his behaviour was not simply that of a nomadic adventurer, but of one desperate to lay down roots, be it through love, or finding a home.

In a 1990 Esquire interview, Rudolf Nureyev definitively claimed to have only loved three people in his life: Frederick Ashton, Eric Bruhn and Margot Fonteyn. Whether platonic or romantic, it seems a meagre inventory for the man who had been incessantly compared to a panther, lion or crow. Nureyev’s love life has been the topic of worldwide intrigue since his defection. In Julie Kavanagh’s 2007 biography of Nureyev, the author spends many of her pages writing about the dancer’s sex life, primarily with men. Several years later, a book by Hollywood biographer Darwin Porter raised a more salacious point of speculation about the late Nureyev’s love affairs: the Kennedys. According to Porter’s source—Truman Capote—the dancer embarked on an affair with the First Lady of The United States, Jacqueline Kennedy, whilst she was living at the White House with her husband. Allegedly, she and her sister Lee Radziwill had been competing for him. Capote claims that the First Lady had suspicions of Nureyev planning to “systematically” seduce every member of her family. And indeed, the book describes Capote as having been shocked to later learn of Nureyev’s affair with the President’s brother and Attorney General, Robert Kennedy. Ultimately, he claims, the First Lady’s relationship with Nureyev ended when she saw that he was pursuing her son, who himself had been dubbed “the sexiest man alive”, JFK Jr.

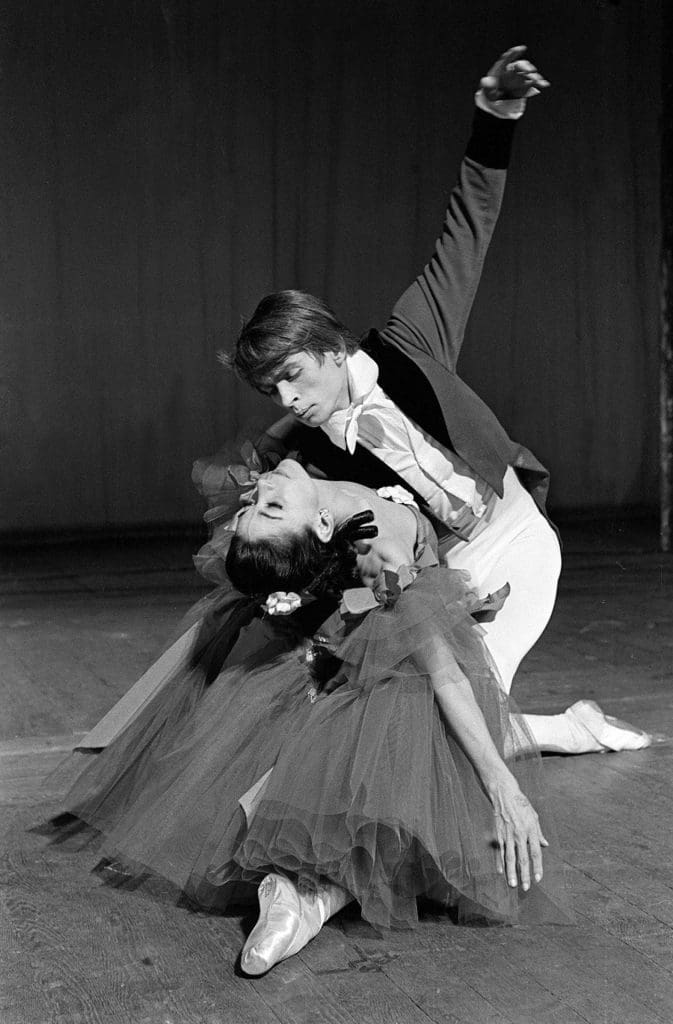

But whilst Nureyev was alive, the greatest prurient question mark over his sex life was to do with whether he did or did not have an affair with British prima ballerina Margot Fonteyn. When the two dancers debuted their partnership in a performance of Giselle that received more than seventy-thousand ticket applications, they took thirty curtain calls, during which Nureyev famously sunk to the ground and kissed Fonteyn’s hand. Their onstage passion led audiences to deduce that they were involved in a real-life love affair. It is a rumour that has long been denied by the ballet world, as well as Fonteyn herself. Nureyev rustled up speculation, by telling some journalists they had never and would never sleep together but telling others that he had made her pregnant. They were entirely wrapped up in one another, with Nureyev even spending his initial months in London residing in Fonteyn’s marital home, so as not to get lonely. They were described as having been like a pair of giddy teenagers, holding hands and hugging in public, whilst experiencing a meteoric rise to fame ordinarily reserved for rockstars. Those who knew the pair cannot call whether their relationship became sexual or not. The Royal Ballet’s famed head choreographer, Frederick Ashton—perhaps the closest to both—once stated that Fonteyn made love to Nureyev only in her mind. In that sense, she was not alone. The whole world was making love to him in their minds.

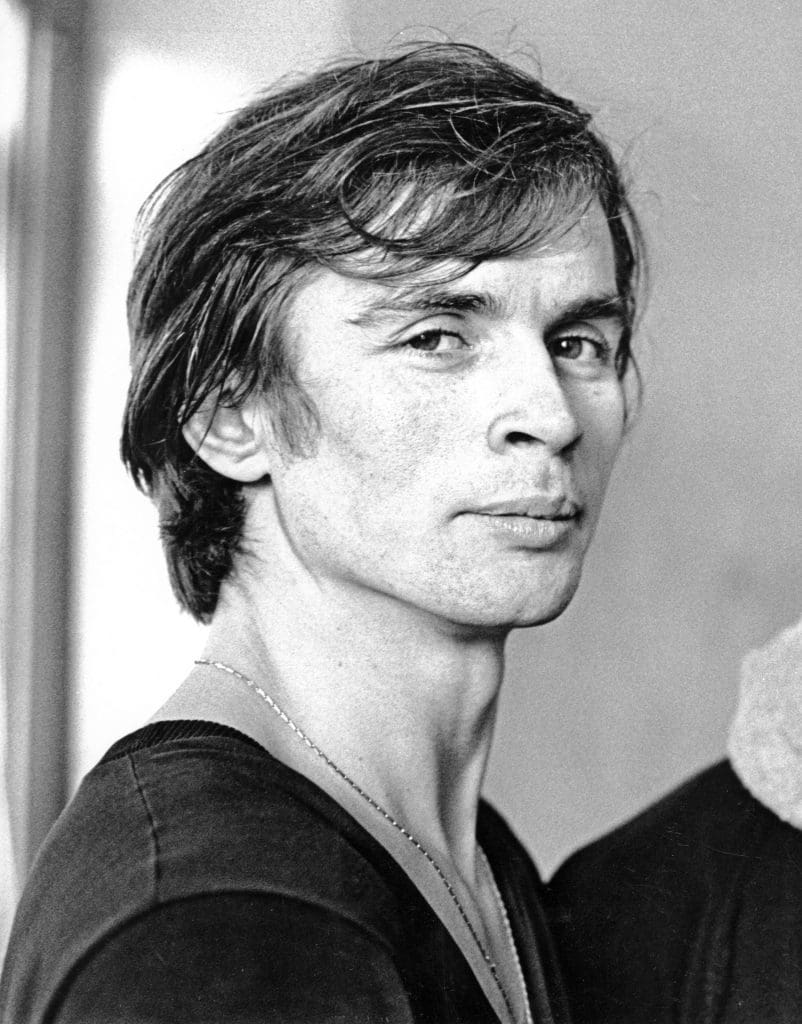

But despite all the sparkling names that appear in Nureyev’s book of romance, his greatest love, whom he was already involved in a tempestuous relationship with when he met Fonteyn, was the Danish ballet dancer, Erik Bruhn. It is unclear how long the relationship lasted, but both men would continue to refer to the other as, “the love of my life,” until the very end, suggesting a vacuum-like quality to the rest of Nureyev’s relationships. Perhaps there was little space for another in Nureyev’s life after Bruhn, given the greatness of his own being and his love for his art. Writing for the Daily Mail, David Wigg quotes Nureyev, saying, “Romance is nice. But my romance is my dance. It is everything to me; my past, present and future.” And indeed, never has a dancer, before or after, had such an impact on the world of ballet. Nureyev modernised classics, such as Swan Lake and La Bayadere, often introducing sex into storylines in unexpected places. He loved his own body, therefore the way he presented himself was elaborate and stylised. He found the classical physique of the male dancer unappealing, thus modelled himself on the female, even standing on demi-pointe, which today is standard for male dancers. Those who knew Nureyev, joked that he wanted to make love to himself. Yet it was not a joke.

But while his dancing career soared, and his sex life continued to intrigue, Nureyev seemed to be searching the world, which he travelled endlessly, for a home. Throughout his life, he owned a farm above Monaco, a lavish Paris salon overlooking the Seine, an apartment in New York’s infamous building, The Dakota—which had long been addressed to celebrities and renowned LGBT+Q artists—a house by Richmond Park, a farm in Virginia and a villa on St. Barts. But it was perhaps the purchase made in the final years of his life, in which he finally found spiritual roots: the islands of Li Galli.

Li Galli is a tiny archipelago of three islands—Gallo Lungo, La Rotonda and Dei Briganti—located right in front of Praiano and Positano. Gallo Lungo, largest of the three, is perfectly shaped like a dolphin. The current owner of the island, Giovanni Russo De Li Galli (such a part of his life are the islands that they have become a part of his family name), who purchased them after Nureyev’s death, tells me that Gallo Lungo is the only one of the islands that was inhabited by Romans, signified by the ruins of an ancient Domus, and that a Greek geographer of the first century BC identified them as the headquarters of Sirenussai—the mermaids. Today, sirens are often associated with lust and danger, savage women luring men to their deaths. But the Classical Greeks saw them as creatures of hidden knowledge. Russo De Li Galli believes that, “the timeless charm of these mysterious creatures has inspired and continues to inspire art and painting.”

Yet it was almost certainly not the sirens that drew Nureyev to Li Galli, for he purchased them from the famed Russian choreographer, Léonide Massine, one of the most important figures in twentieth century dance. Not only that, but Massine had acquired the islands in the 1920s with the help of Sergei Diaghilev, founder of the Ballet Russes and the Godfather of Russian ballet. By then, Diaghilev lived in Positano and assisted Massine in obtaining the islands, which were then just rocky formations swarming with mosquitoes, from the Parlato family. The story goes that Mrs. Parlato was standing on the beach of Positano, shouting, “I have found a crazy man who bought the rocks!” Massine was responsible for transforming the islands into what they are today. He planted trees all over and erected a splendid villa with the help of French architect Le Corbusier. When Nureyev purchased Li Galli, it had been uninhabited for a decade and he restored it magnificently. He planned to open a ballet school there, but died of AIDS before his dream could be realised. Today, Li Galli continues to honour its tradition, hosting residencies for artists, run by the Fiorucci Art Trust.

Shortly before his death, at the age of 54, Nureyev told a Danish newspaper, “I am the sexiest man alive. Just ask Lee Radziwill. Just ask Jackie Kennedy. And if you don’t believe me, ask Bobby and John-John Kennedy. Nobody can resist me. Everyone who has gone to bed with me has fallen in love with me.” It is a heart-breaking cry for validation, from a man meeting the tragic end of a remarkable life. But if such a perception was truly of such importance to Nureyev, then one might conclude that Nureyev could rest peacefully. For not only had he found a home in Li Galli, but the world had created, in his image, the greatest lover of all time.