Once asked to define happiness, Tennessee Williams replied with, “Insensitivity, I guess.” Albeit unexpected, it gives a sense of the American playwright: a tortured genius and poet of the human heart. “He had X-ray eyes,” said Maria St. Just, an intimate and co-executor of Williams’ will. X-ray eyes that felt “the tiniest desire, the tiniest rejection, the tiniest affection.” Forty years after his death, Tennessee Williams remains relevant as ever. Successful revivals of A Streetcar Named Desire and his other major plays continue. And then there’s the stream of academic articles and studious biographies such as John Lahr’s Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh. Williams, who passed away at seventy-one years old, was the author of more than twenty-four full-length plays including The Glass Menagerie, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Sweet Bird of Youth and The Night of the Iguana. His innovative drama and sense of lyricism revolutionised post-war American theatre and made the five-foot-three writer into a giant.

“He was always my favourite,” says Sir Christopher Hampton who met Williams in London, weeks before he died in 1983. “We had a long, long conversation about all the films that had been made from plays of his,” recalls Hampton, the multi-prize-winning playwright and screenwriter. “He didn’t care for any of them. A few grudging words for Streetcar but even that was not entirely satisfactory. He thought that they had all been censored.” The supper held at the Belgravia home of Maria St. Just was memorable. “Tennessee was in an extremely good mood and very entertaining,” Hampton continues. “He had been in Sicily and said that he had been depressed but was feeling better.”

This contrasts with Peter Eyre’s experience who dined with Williams and Marguerite Littman, the Southern Belle and AIDS activist, at San Lorenzo, the London restaurant. “Tennessee was drunk and fell asleep for a bit,” says the British actor. “When he woke up, he tried to flirt with a waiter and told him he was beautiful.”

Whereas the author Gore Vidal, who fondly referred to Williams as ‘The Bird’, found him in “a manic mood” when they were working on the screenplay of his short play Suddenly Last Summer. Vidal “knew so little about drugs then” but ‘The Bird’ seemed to be popping uppers, downers and also speed.

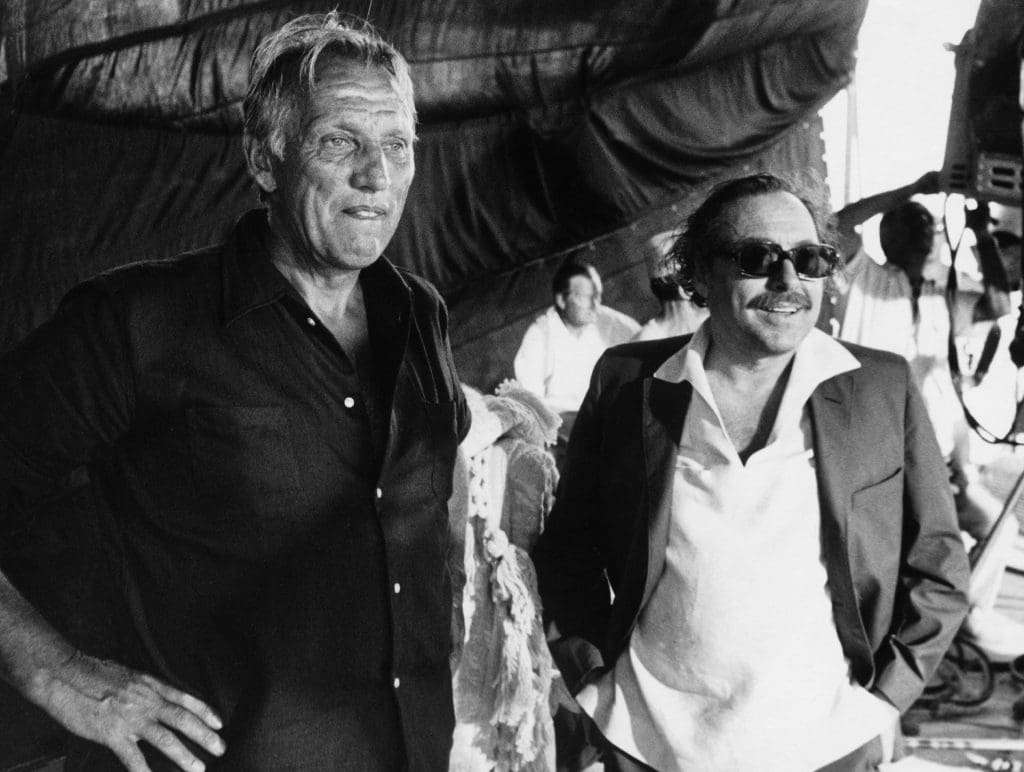

Delving into Tennessee Williams’s life, it’s essential to realise that he was beset by mood swings and demons brought on by pills, drugs and booze, but his body of work also led to twelve movies starring Hollywood stars such as Vivien Leigh, Paul Newman and Elizabeth Taylor. And he was courageously gay. During the making of Boom (1968) based on his play The Milk Train Doesn’t Stop Here Anymore, both the film director Joe Losey and his girlfriend Patricia Mohan were “surprised and moved by Tennessee’s ease when talking about his sexuality.” “Coming out then was unusual,” writes Patricia Losey in Mes Années avec Joe Losey. Lest we forget, when Williams became an overnight success in 1945, practising homosexuals were not in the closet, they were in a bunker. And unlike the writer Truman Capote who yearned to be accepted by high society, Williams did not care. According to Memoirs (1975), his autobiography, Williams believed in “the Quixotic notion” that he could “enjoy all kinds of society, the bohemian and the elite, the straight and the gay.” True, Memoirs is bawdy—too explicit about his sexual conquests—but it’s also moving. After screaming “I hate the sight of your ugly old face!” at Rose Williams—she had tattled on him—the playwright describes his schizophrenic sister as “wordless, stricken, and crouching.” “This is the cruellest thing I have ever done in my life,” he admits. “And one for which I can never properly atone.” (Of note, Tennessee Williams and then his literary estate would financially care for the lobotomized Rose, the inspiration for Laura in The Glass Menagerie, until she died in 1996.)

And there are Memoirs’ playful moments: The then friendly Capote and Vidal are arrested when breaking into Williams’ Key West home. The French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre becomes a no-show at Williams’ party in Paris in spite of sending bulletins “off and on during the evening” and being just around the corner. “I suppose he regarded me as too bourgeois or American or God knows what,” Williams offers. And when Thornton Wilder pontificates about Stella being incapable of being attracted to the lower-class Stanley, Williams describes the Streetcar cast as politely sitting there and listening to the older playwright while he privately decides that Wilder “has never had a good lay.”

On form, Tennessee Williams rarely failed to charm. “He was such a wonderful, sweet man,” says the actress Marisa Berenson. “ I think he was shy and felt a little lost. We laughed a lot, like children.” Indeed, all the paparazzi photographs taken over the years capture Williams’s charisma, fun and appeal; even during the 1960s that he coined his “stoned age.” Snapped in Rome during the 1950s, the playwright sums up attentive to the actress Anna Magnani; ever the Southern-born gent, Williams appears boyish and bow-tied at the première of Suddenly, Last Summer next to a nervous Elizabeth Taylor; outside the Venice Film Festival in 1972, a dapper Williams relaxes beside Marisa Berenson sporting a vast-brimmed hat; at the Cannes Film Festival in 1976, he and Charlotte Rampling joyously mug for the cameras and during the re-opening of Studio 54, Williams seems bright-eyed and keen next to a tight-lipped Maria St. Just. “My mother was horrified by the scene,” says Natasha Grenfell, Lady St. Just’s youngest daughter.

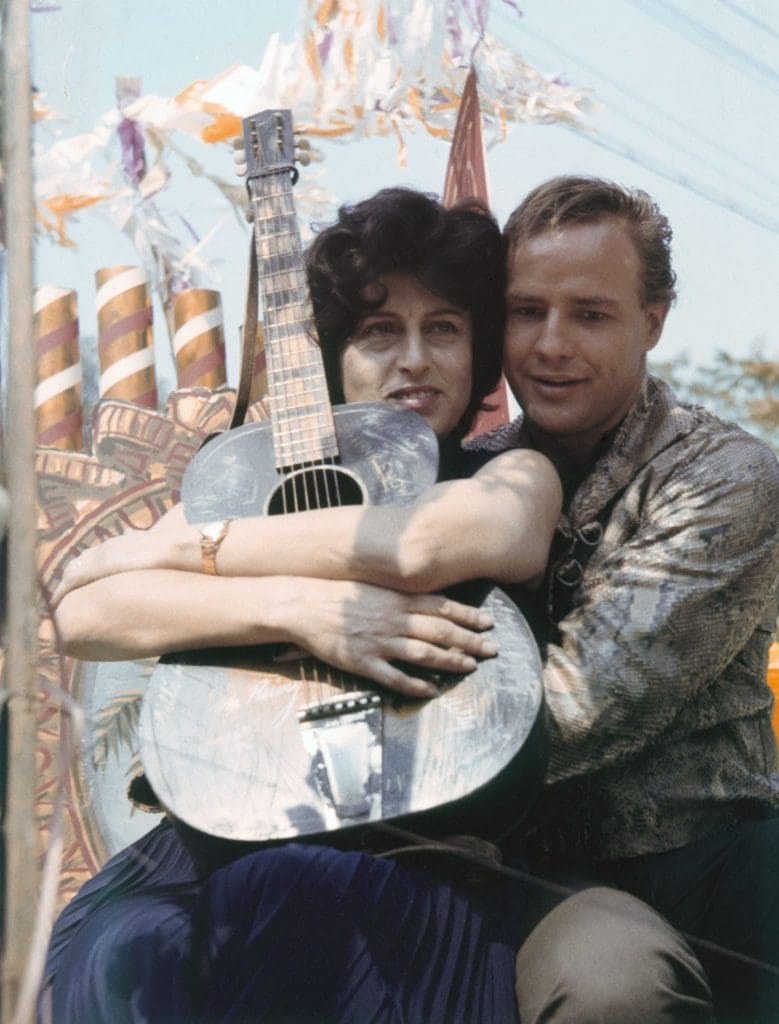

Headed by Paolo di Paolo’s portfolio of portraits, there seem to be several album’s worth of Magnani and Williams. Soulmates: they are photographed in the kitchen, on the beach, driving around in one of Magnani’s splendid cars and waving from Andrea Doria—an ocean liner headed for America. “She was beyond convention,” Williams enthuses in Memoirs, published after Magnani died from pancreatic cancer in 1973. “And I suspect that was our great bond.” Tanya Lopert met the dynamic duo at the sumptuous apartment of director Francesco ‘Citto’ Maselli in Rome. “It was a get together of the movie industry and the Italian intelligentsia,” the American actress says. Past midnight, Tennessee and Anna went off feeding stray cats. They’d start off at the Villa Borghese and stroll all around Rome.”

Magnani was not a morning person. “Her shutters were closed throughout the day,” recalls Lopert. But after 2:30pm, Italy’s favourite prima donna would call Williams and say, “Ciao Tenn, what is the program?” Their relationship inspired two plays, The Rose Tattoo and Orpheus Rising. Wisely, Magnani refused to act on Broadway—her English was not good enough—but she won an Oscar for the film version of The Rose Tattoo and starred alongside Marlon Brando in The Fugitive Kind, based on Orpheus. Smitten by her earthy confidence, Memoirs describes restaurateurs and waiters receiving her like a queen, “while she ordered wines, pastas, salads, entrees without consulting the menu.”

Others may have seen Magnani as a tragic woman who was dumped by both the director Roberto Rossellini and the father of Luca—her polo-stricken, invalid son—but Williams viewed her as an exalted actress who “managed to live within society and yet remain so free of its conventions.” His romantic attitude might have been generated from his fathomed passion for Italy. The country calmed him. Williams spoke the language and was always looking out “for that mythic little farm” in Southern Italy or Sicily where he could “raise goats and geese” and “finish one more play.”

Just as Frank Merlo (1922 – 1963) the great love of Williams’ life was of Sicilian extraction, Luchino Visconti also played a powerful role. In the late 1940s, the director introduced Zoo di vetro (The Glass Menagerie) to Italy, soon followed by Un tram che si chiama desiderio (A Streetcar Named Desire.) During rehearsals, Williams was called Blanche by Visconti until he kicked him out, exasperated by the playwright’s strange laugh, particularly in response to queries about Streetcar.

Throughout his career, Williams’ laugh was remarked upon. Backstage, leading actresses complained to the management about the off-putting giggle; only to be informed that it was “Mr. Williams.” When seeing Claire Bloom in Streetcar (1973), Christopher Hampton remembers “this weird noise” in the background. “And I looked round and there was Tennessee,” he says. Laughter or not, Williams joined Visconti’s coterie that included Franco Zeffirelli, his handsome and blond Florentine assistant. And in 1954, the playwright wrote unpaid dialogue for Senso because it was helping his dear friend Maria Britneva, the future Maria St. Just. They had met in London through John Gielgud. The White Russian-born Britneva was a struggling actress who resembled a young Barbara Stanwyck but the pint-sized version. Britneva, a former ballerina, was barely five-foot but made up for it by her personality and indomitable spirit. “Maria was so outspoken and so definite,” says Hampton.

In 1990, when promoting Five O’Clock Angel—Letters of Tennessee Williams to Maria St. Just 1948-1982, she informed the New York Times that she was the model for Maggie, in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. But instead of being flattered, St. Just feigned disappointment. “I wanted a lovely Russian princess in a sleigh, covered in sables,” she admitted. “When I saw him, I said, ‘what is this Tennessee?’ And he said, ‘it’s your spirit, your tenacity, your vitality. That’s what I’m really writing about.”

Maria was an adventuress—scarred by an immigrant’s penniless childhood—who required financial security. In July 1956, she married Peter Grenfell, the second Lord St. Just. He was the only son of Edward Grenfell, a member of parliament, a director of the Bank of England and partner of Morgan, Grenfell & Co, the English branch of J.P. Morgan. Unfortunately, the handsome and elegant Peter suffered from severe manic depression, but Maria admirably coped and raised their two offspring. She was accused of not making the marriage work when her husband could slip off for cigarettes and disappear for six months.

Geraldine Harmsworth, a close family friend, recalls Maria’s drive, wit and tremendous flair. “There were amazing dinner parties,” she says. “In front of guests, her daughters Katya and Natasha would perform the dying swan.” Both little girls drank their milk from big silver christening mugs. “It was very glamorous, Maria was living on the edge, playing up her white Russian roots,” continues Harmsworth whose mother was Patricia, Viscountess Rothermere, a former Rank starlet. Hugo Guinness considers Maria his first self-invented character. “She didn’t fit into London society,” says the British artist and illustrator, known for his Wes Anderson collaborations. “Being Russian was unique then and she was unusual for also speaking Italian and French.” Since Williams was a morning writer, Guinness reckons that St. Just was the playwright’s afternoon distraction. “Maria was a hybrid of formidable woman but also handmaiden,” offers Geraldine Harmsworth.

High on drama and power, Lady St. Just could be polarising and offensive. “Are you a lesbian?” she asked one of Guinness’s relatives who’d cut off her hair. “What a hideous necklace,” Maria quipped when informed it was new. Or “how common to lock the loo door” when a guest had been jammed in the downstairs gents, for two hours. “She did think some people were her inferiors and did behave badly, I imagine,” says Hampton. And there were the nicknames. Although Guinness revelled in being called the agent provocateur, a fashion stylist resented being called the mosquito. Meanwhile, Laura, Maria’s stepdaughter, was known as Snow White.

Depending on her behaviour, Williams either described St. Just as “close and dear” to his heart, admiring “her fantastic love of fun” or referred to her as the “raging tartar” who was “afflicted with folie de grandeur.” Three tales speak volumes about their friendship. The first concerns their being held up at knifepoint in New York. “How dare you? When you’re still young enough to work,” roared the outraged Maria. Whereas Williams was frantically handing out fists-loads of dollar bills to their attacker. The second story occurred after seeing Martin Sherman’s Bent on Broadway, starring Richard Gere in 1979. Backstage, Williams had held out his hand, but Gere had ignored it. “Don’t you know who’s extending his hand to you?” St. Just bellowed. “It’s Tennessee Williams, the world’s greatest playwright. How dare you not take his hand!” And the third concerned Maria St. Just’s aim for the limelight. Even in her later years, she tried auditioning to play Stella. One night, Peter Eyre had watched the film Streetcar with her. “Whenever Vivien Leigh spoke, Maria repeated her lines,” he says. “It didn’t stop.”

Every weekend, Wilbury House became Maria St. Just’s stage. Weaving a web in the Wiltshire countryside, she managed to gather bold names from the theatrical, ballet and film world sprinkling in members of the English jeunesse dorée—the children of dukes, press barons, banking dynasties as well as rock star wives. Wilbury, a renowned neo-palladian house, belonged to her husband’s family. “It was staggeringly beautiful with two wings and a farm,” says Guinness, who rented the nearby Rose Cottage. “Wilbury was Chekhovian,” says Harmsworth. “And Maria kept that all alive with the déshabillé style of pots and plants outside and pillars peeling paint.” Guinness recalls Maria’s ‘ball of energy’ and large Labradors with names like Tosca contrasting with her deeply depressed husband Peter and their adult children. “They would sit there, drinking coffee and chain smoking,” he says.

Tennessee Williams often stayed at Wilbury. “He was pretty medicated, nodding off at lunch and then coming up with one-liners.” Harmsworth viewed him as “a clever dormouse.” “And Maria would say, ‘oh do shut up Tennessee’ but it was delivered with warmth,” she says. St. Just made him laugh. “Tennessee was a daydreamer and she filled in the gaps.” Maria St. Just had also extended an open invitation to his sister Rose Williams who remained institutionalised. The idea had appealed. “It would be fun to establish Rose as a lady sovereign, with ladies curtsying to her and gentlemen bowing,” Williams wrote.

Some complained that Maria St. Just was too possessive of the playwright or just plain invasive but she was always there, on the other end of the telephone, hearing about the insomnia, claustrophobia and tales of his sinking reputation. After the success of The Night of the Iguana 1961, Williams’ work slipped. “I always thought there were beautiful things in all his plays,” says Christopher Hampton. “But the organising principle somehow dissipated and he wasn’t able to focus long enough.”

And then Tennessee Williams died quite suddenly. His lifeless body was discovered in his New York hotel room. The cause of death was asphyxia. When ingesting barbiturates, Williams choked to death on a plastic bottle cap. Still, it is hard not to agree with Elia Kazan who midwifed his best plays. “Don’t feel sorry for him,” the director cautioned in his eulogy, written for Williams’ memorial. “The man lived a life full of the most profound pleasures, and he lived it precisely as he chose.” Feelings formerly affirmed by Williams who wrote that for someone “so nearly destroyed so often,” he had led “a remarkably fortunate life which has contained a great many moments of joy, both pure and impure.”