Cinema is a reflection and catalyst for all walks of life. The stories we see on screen, showcased in stunning sequences and through naturalistic performances are employed by filmmakers to execute visceral and intellectual experiences in a way only film can. These components simultaneously speak to numerous communities that have seen minimal representation elsewhere and invite others to experience their unturned circumstances. The queer community, especially, is a group that cinema has called to through artistic delineation encompassing identities that love outside the heteronormative boundaries or challenge the restrictive agenda around gender expression and experience. Academics working in the medium have coined distinct movements as a means to classify numerous waves within the cinematic realm, one of which being the New Queer Cinema, where the queer community can prosper in visual storytelling.

Conceived in the September 1992 issue of The Village Voice (and re-printed in Sight & Sound) by independent and queer cinema scholar B. Ruby Rich’s observations, the New Queer Cinema movement is artistically defined by cinematic observations of any identity that defies the gender binary and/or heteronormative standard. This includes openly gay, transgender or bisexual characters being depicted in movies as a means to portray the queer experience to those inside and outside the LGBT+ community. Despite prevalent spotlight and mainstream media attention taking place from the 1990s, theorists claim the movement has in fact pre-existed since the 1930s, using French poetic filmmaker Jean Cocteau’s visceral and ever-lasting The Blood of a Poet (1934) as an example, combining the avantgarde with the queer film movement to accentuate the idea of challenging and existing outside the “sacred” tradition in both life and art. Additional faces that became associated with the movement include the gay artist Andy Warhol and lesbian filmmaker Chantal Akerman in the 1960s. This was soon followed by the bisexual actor River Phoenix, who experimented with his sexuality during the filming of Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho in the early 1990s, another definitive New Queer film.

Born a whole decade before the trail-blazing and world-shifting Stonewall Riots, which thrust the LGBT+ community’s rebellion and fight for equality into the mainstream, Japanese-American filmmaker Gregg Araki quickly became known as a new pioneer of New Queer Cinema through his radical approach to adapting queerness to the screen, encompassing unconventional visual choices and narrative structures. The director previously identified as gay throughout the early to mid-1990s, before entering a relationship with actress Kathleen Robertson in 1997, later telling Out magazine in 2014: “I don’t really identify as anything. I probably identify as gay at this point, but have been with women.” Araki recruits the camera and screen as a vessel for the queer community’s voice to take centre stage, where no stone is left unturned and where an unapologetic and boundary-breaking portrayal is the manifesto for his artistry.

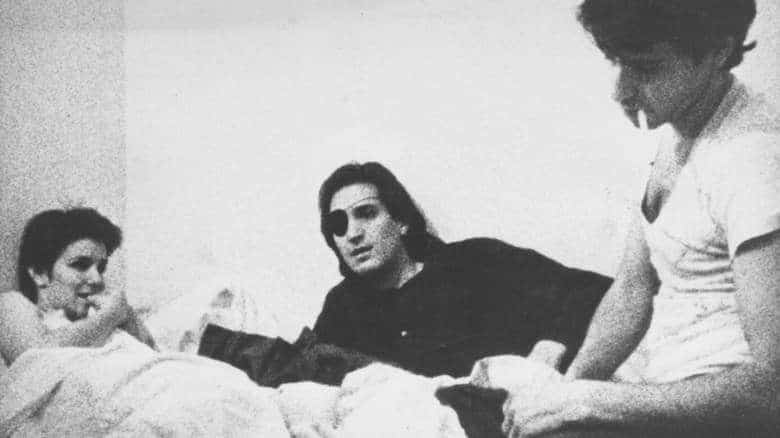

Araki’s artistic debut came in 1987 when he directed Darcy Marta, John Lacques, and Mark Howell in the poetic drama Three Bewildered People in the Night. The director’s first film follows telephone and cafe conversations, the deterioration of a heterosexual couple (Marta and Lacques) and the subsequent forming of a queer one (Lacques and Howell). His sexually-charged introduction to visual storytelling utilises a $5,000 budget to communicate a tapestry of sentiment, angst and the unexpected paths to love. The filmmaker exhibits these ideals in stunning shot composition showcasing Los Angeles’s artistic landscape-all in true anti-Hollywood fashion. In its depiction of battling against gender norms and experimenting with sexuality in the search for one’s self, Araki’s queer artwork expresses the vulnerability that conjoins the community’s heart and soul. The expressive lighting combined with story exposition coming from the three characters’ providing heartfelt soliloquies demonstrated Araki’s experimental artistry. This artistic effort earned the director the Ernest Artaria Award at the Locarno International Film Festival in 1989 and a definitive spot in the New Queer Cinema movement. Three Bewildered People in the Night defies boundaries by being both individual yet collective in its narrative, showcasing the struggles of feeling lost and out of place, the protagonists lay their most raw issues of falling out of love and into forbidden passion out on the table.

The Long Weekend (O’ Despair) followed Three Bewildered People in the Night two years later and featured Bretton Vail, Maureen Dondanville, Andrea Beane, Nicole Dillenberg, Marcus D’Amico and Lance Woods as three couples, two gay and the other straight, who spend a weekend together. Araki’s sophomore feature is classified as a low-budget drama film, again made from $5,000, that holds up the New Queer Cinema movement through its direct portrayal of queer love. The cult film delves into an emotional nerve that is more turmoil than tenderhearted, however, as stated in the title, betrayal and sentimental bruising fester behind the images of passionate love, eventually boiling over to infiltrate the surface. The Long Weekend (O’ Despair) earned Araki his second accolade, the Independent-Experimental Award, at the 1989 Los Angeles Film Critics Association through its stylistic approach of black-and-white filmmaking and ability to transcend a minimal budget to create a hard-hitting piece of emotive art that calls profoundly to New Queer Cinema through centring two openly queer couples in its visceral and heartbreaking narrative.

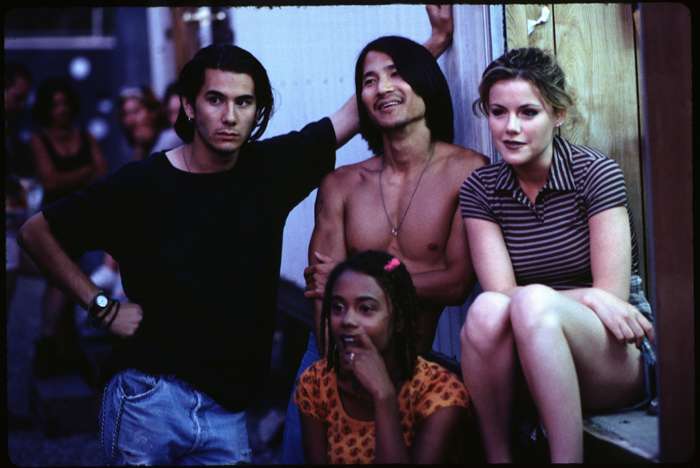

In 1993, Araki began his Teenage Apocalypse cult film trilogy with Totally F***ed Up, a drama film starring James Duval, Roko Belic, Susan Behshid, Jenee Gill, Gilbert Luna, Lance May, Alan Boyce, Craig Gilmore and Nicole Dillenberg as six gay teenagers who make up a chosen family (a signature queer trope). Araki divided the narrative into an episodic format with a linear structure featuring the teens fluctuating alongside segments of unrelated material as diverse tangents, with opening titles splicing off a total of 15 parts, further cementing his experimental approach to the camera. The filmmaker told Indiewire to think of the handheld camera recorded piece as “a rag-tag story of the fag-and-dyke teen underground….a kinda cross between avant-garde experimental cinema and a queer John Hughes flick.” Totally F***ed Up, made on 16mm film with no crew other than the director himself, crashed into the 1993 Sundance Film Festival in all its expressive queerness, post-punk angst and indie scene sentiment as an immersive blend of tonal composition to further prove its creator’s highly held placement in experimental queer filmmaking. The film showcases some forward-thinking in its thematic values, celebrating sexual liberation in its central gay characters who question traditional values in the thematically aligned settings of underground hangouts. Araki manages to embed a sense of chaos in the film’s coded meaning, replicating the free-spirited and burning passionate nature of the ’90s youth culture who share every ounce of their queer experiences directly with the camera. This laces Totally F***ed Up with something so personal and intimate that it can strike a nerve without realising it. Hailed as a formative pioneer of the New Queer Cinema genre, Araki’s fourth feature presentation is a tale of emotional depth that cements itself firmly and unapologetically in its sentimental factors. It’s melancholic yet liberating in its value-driven narrative, finding a soothing grey area between the desolate and hopeful as these teens strive to show who they are regardless of what society has told them to think of it.

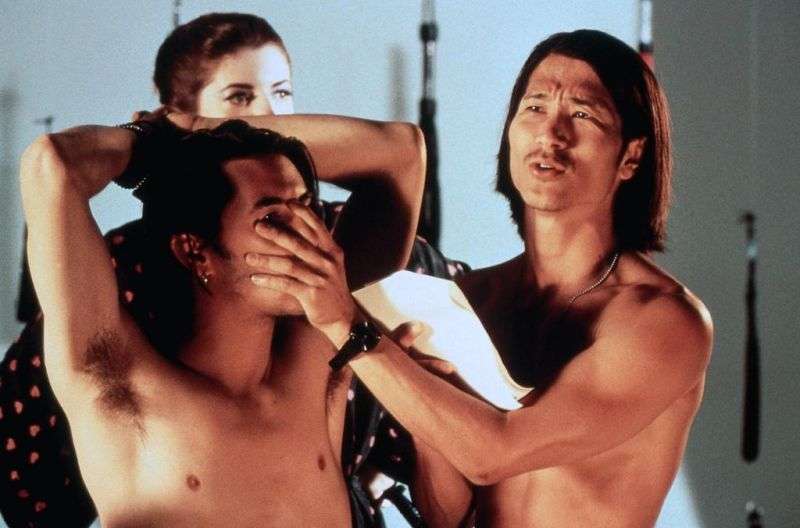

12 years after he made his debut, the filmmaker released Splendor, an unorthodox romantic comedy featuring Kathleen Robertson, Johnathon Schaech, and Matt Keeslar as a throuple, becoming a rare rom-com that openly showcases polyamory and bisexuality. Araki was clearly aware of how this 1999 love film differed from the standard releases of the time which defined the rom-com trope of that era, such as Pretty Woman or Notting Hill. He shared with Filmmaker Magazine how he directed this screwball comedy under the idea of defying conservative norms, stating it was “very much about trying to live by your own rules…about achieving conventional happiness in an unconventional way.” The synopsis upholds this concept as Robertson’s character Veronica, a struggling actress, finds it difficult to choose between the passionate writer Abel (Schaech) and the vigorous drummer Zed (Keeslar), so instead dates both of the men who eventually grow closer themselves. Splendor challenges the standard romantic comedy not only in its subject matter but also within its visual exposition. Unlike other directors depicting the cliche and, now questionable, romance tropes centred on female objectification, Araki throws out the hetero-male gaze through an elimination of female nudity which is replaced with close-up shots of the male counterparts as nude models. This subtle yet groundbreaking vision displays additional defiance of genre boundaries alongside his portrayal of queer love.

2010 saw the release of Araki’s tenth feature Kaboom at the Cannes Film Festival where audiences were invited to witness Thomas Dekker, Juno Temple, Haley Bennett, and James Duval as a group of college students engaging in numerous sexual escapades in between probing an unorthodox cult. Made under a budget of $539,957, Kaboom is the loudest demonstration of Araki’s sensibilities, showcasing the utmost debauchery and sexual liberation across numerous identities. The film thrives in its psychedelic foundations as a way of transgressing depictions of queer lifestyles, with Araki employing bold colour, flashy editing and his trademark low-budget, anti-studio system approach in his further exploration of queer cinema. These bombshell visuals only elevate the openly queer narrative depicting WLW sex scenes combined with unapologetic discussions surrounding the details of sex itself. Through this, a kicking quirk has been threaded throughout Araki’s vision where rules don’t even have a chance of applying and capturing the vibrancy and experimentation which the queer community flourishes from. This exact artistic approach is what earned Araki’s Kaboom the first-ever Queer Palm after its debut at Cannes, being immediately recognised for its spotlight on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender stories.

Araki’s filmmaking is at its most powerful as a rejection of any restrictions or rules dictating what queerness should look like on-screen. The writer and director is a true auteur committed to a contextual cause, utilising his visual style and storytelling to translate a community that has risen above the hardships and turmoil placed upon them by bigotry and a refusal to understand. Through his taste for the shoegazing genre, a combination of alternative rock and indie music recognised by obscured vocals, distorted guitar instrumentals and overwhelming volume in a feedback expression, the filmmaker combines various artistic mediums as a means of expressing his untraditional queer narratives, and, like the most enduring queer filmmakers, he does it without an ounce of compromise.

Want to read more about New Queer Cinema? Check out our essay on John Cameron Mitchell’s gloriously fluid Shortbus here!